A Museum of Doing

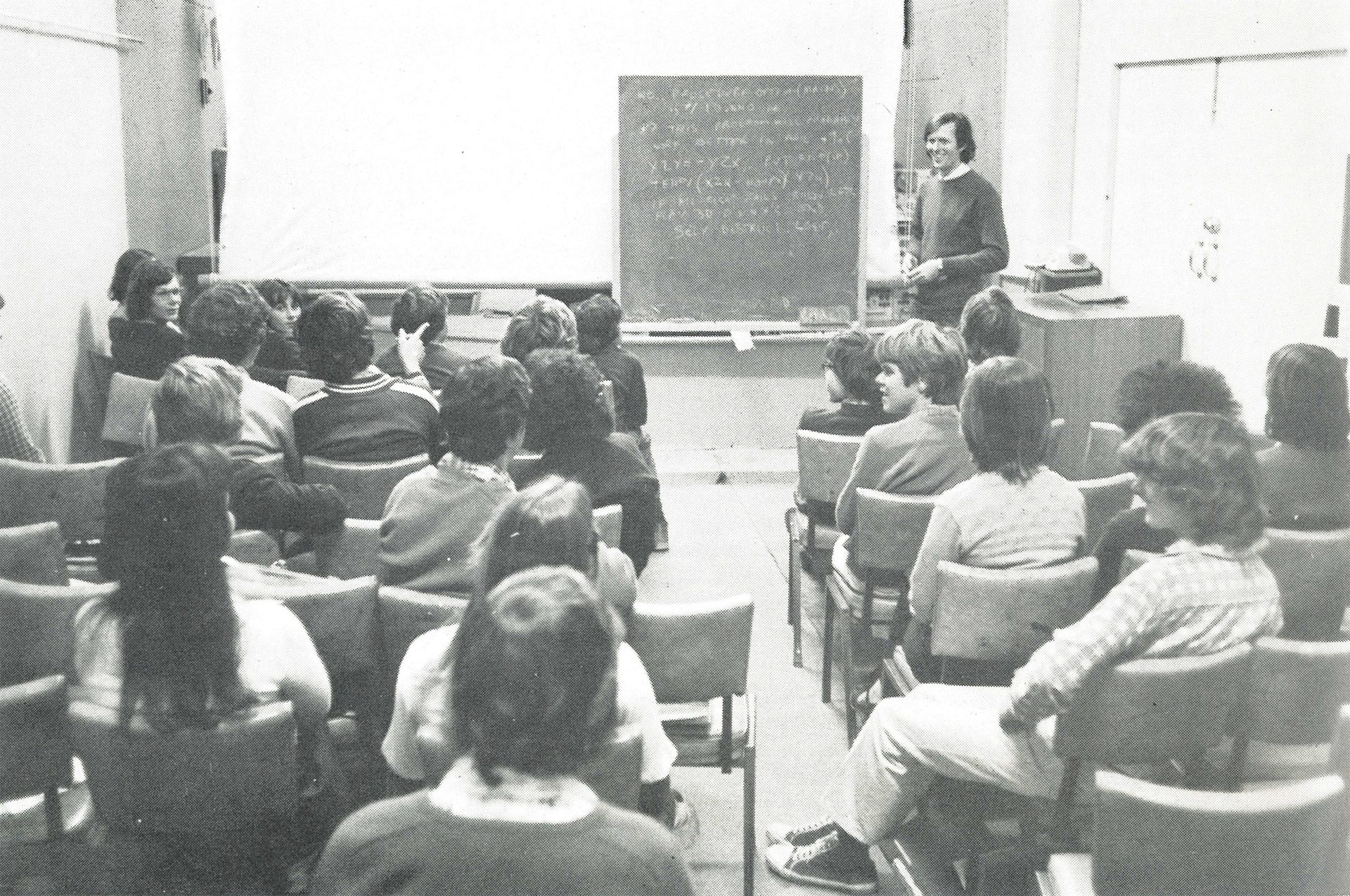

‘All technical schools should have an immediate connection with a museum. The eye sees in a moment what the mind cannot understand from a written description’

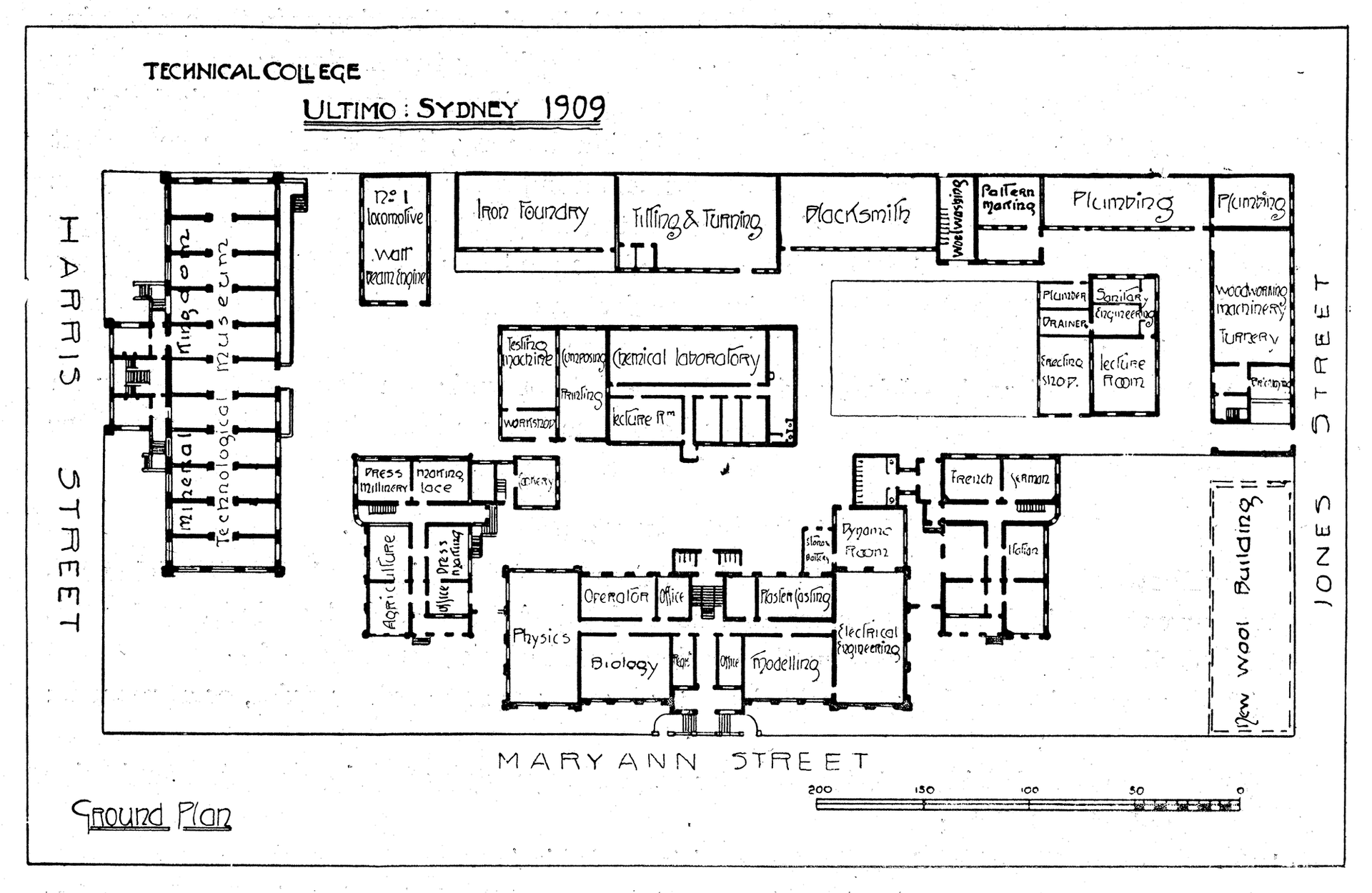

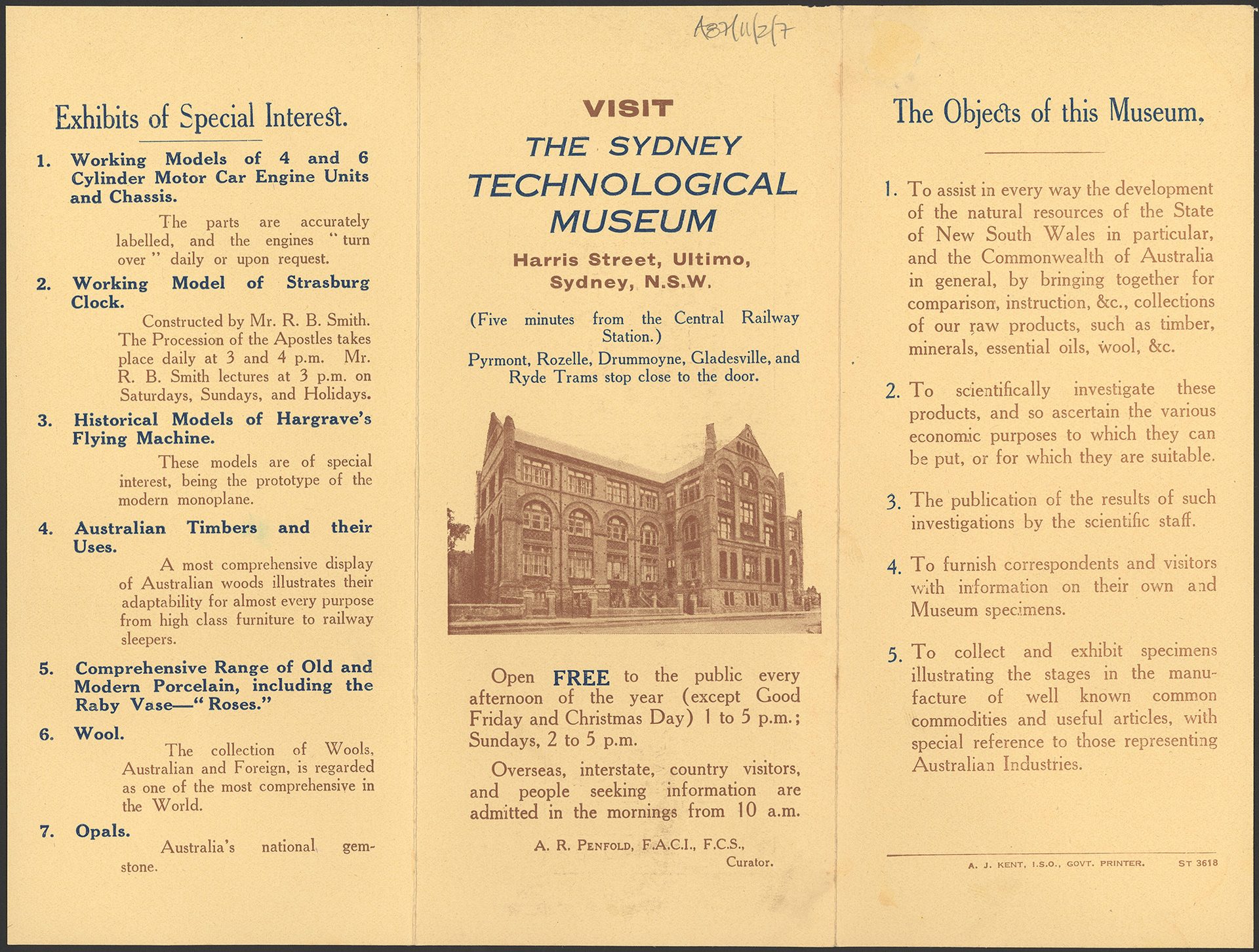

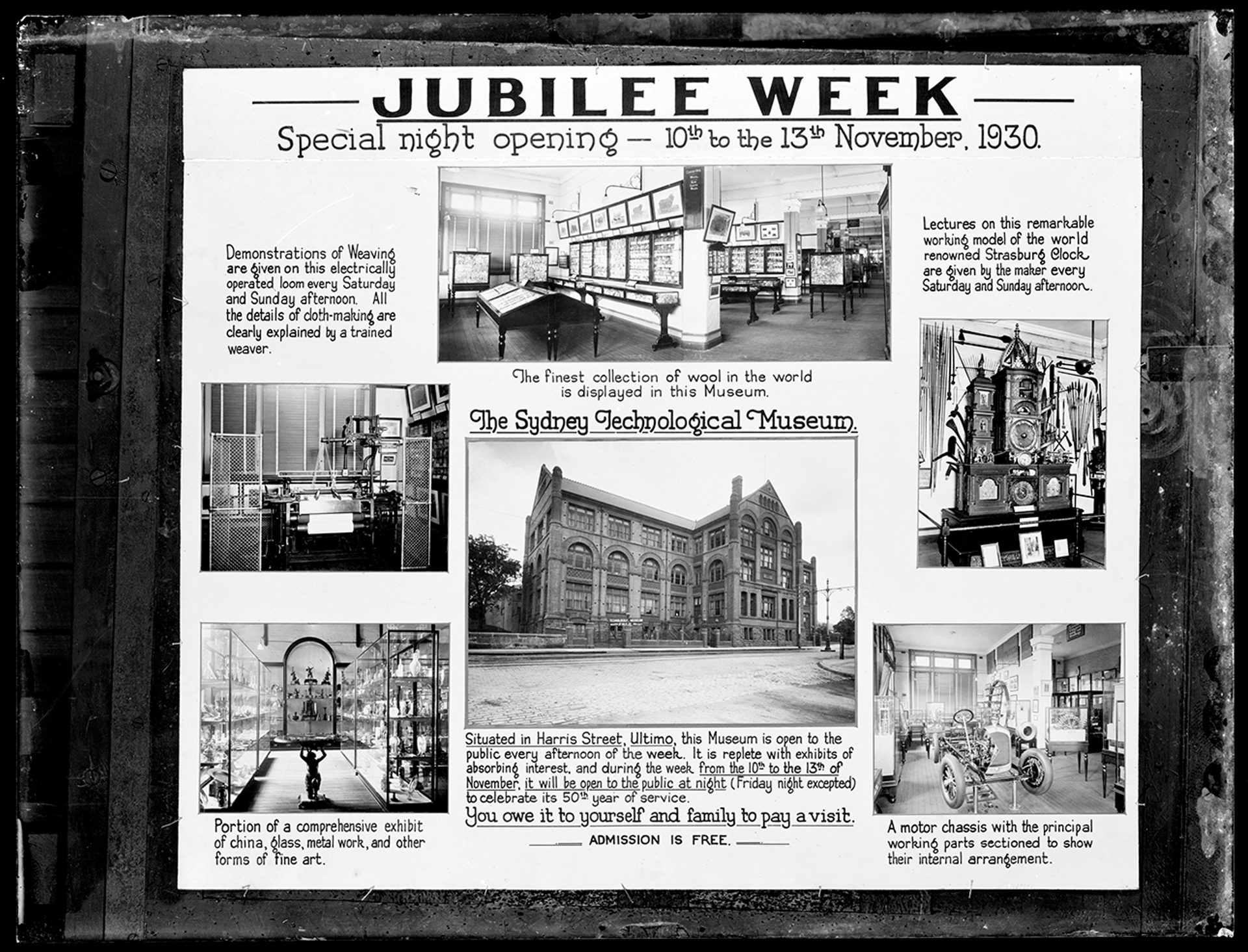

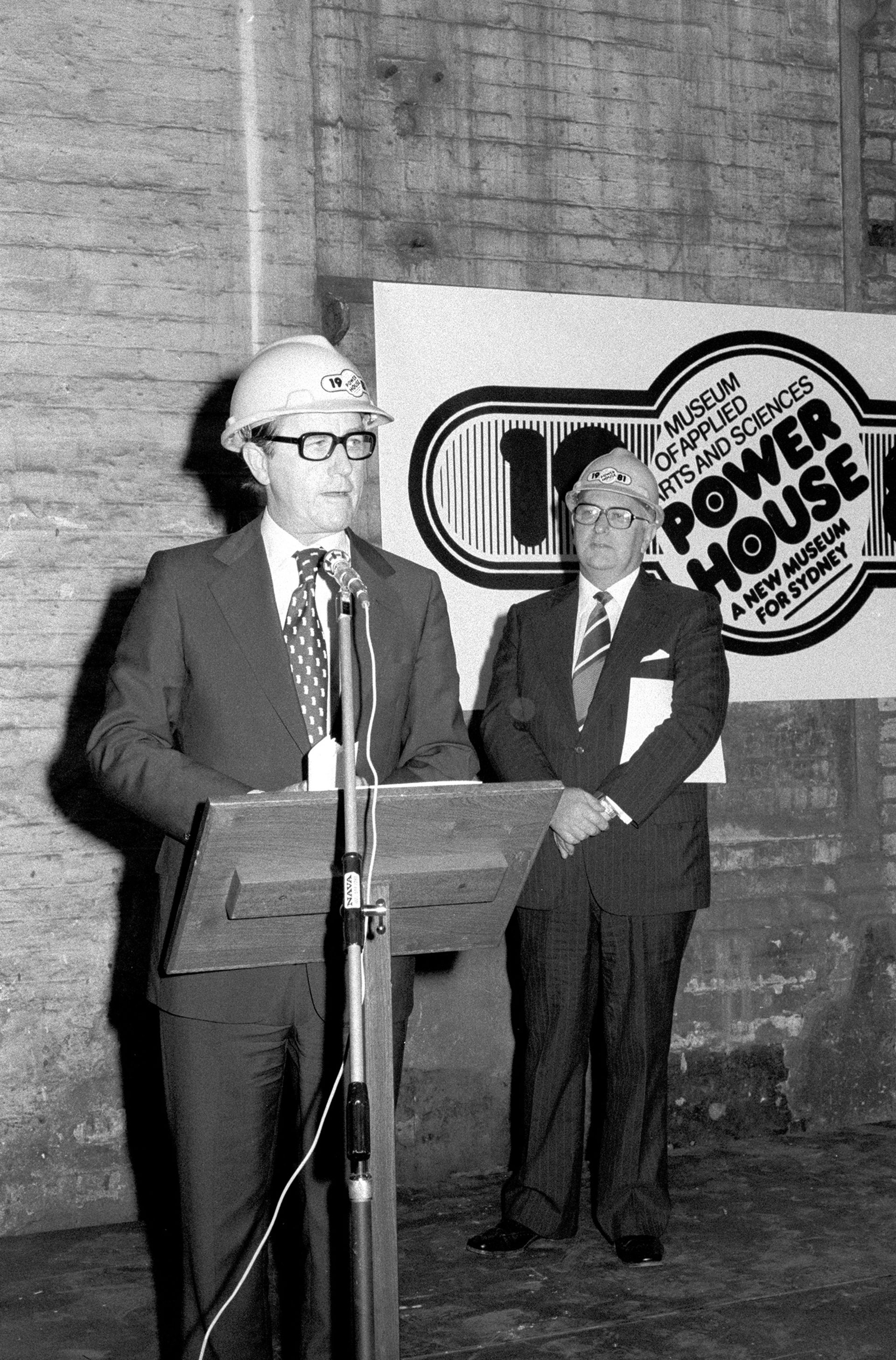

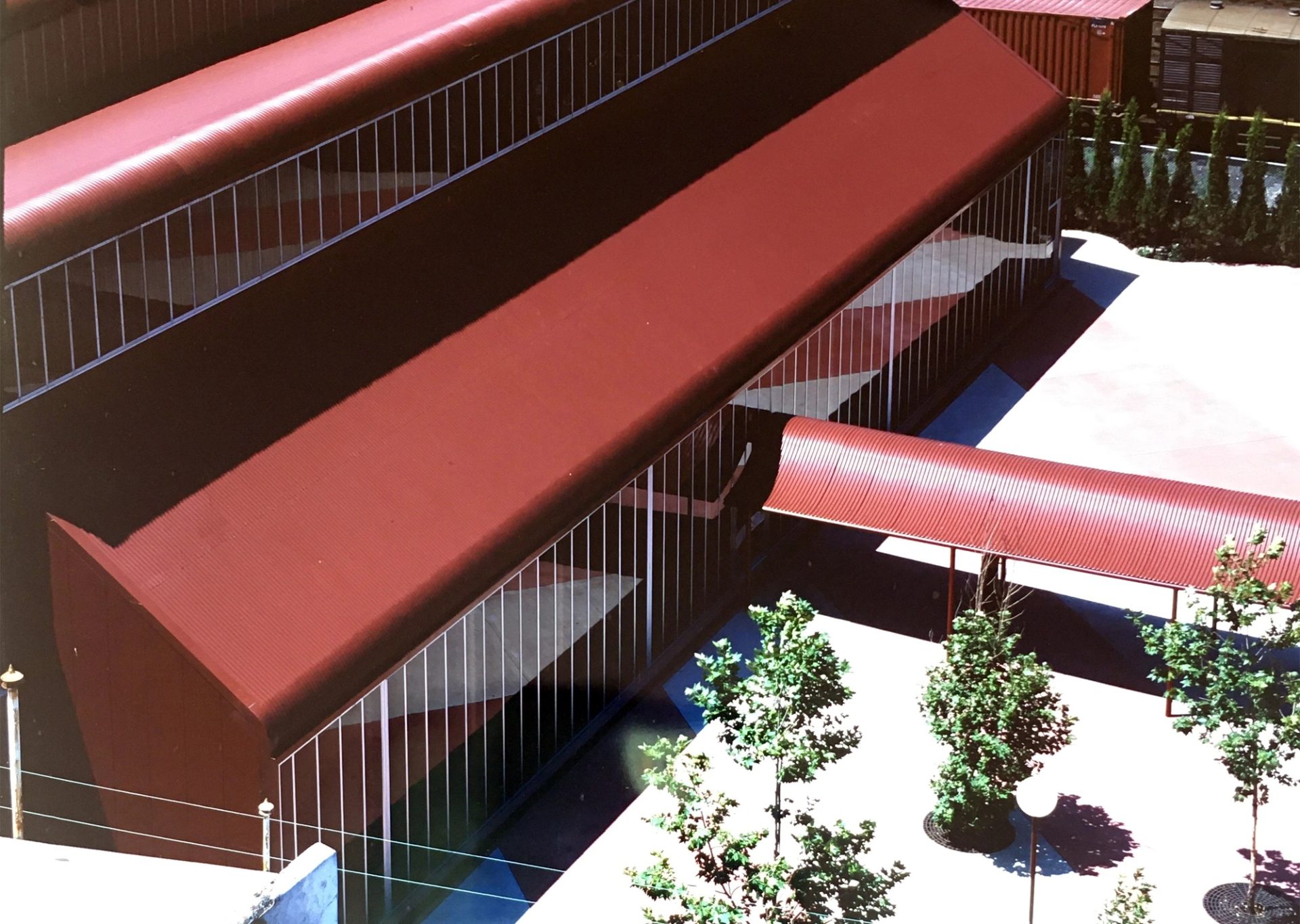

On 4 August 1893, the governor of New South Wales, Sir Robert Duff, opens the purpose-built Sydney Technological Museum. The building – on Harris St, Ultimo – is designed by the Government Architect W E Kemp in ‘the spirit of Romanesque.’ Three-storeys high, it and its companion, the Sydney Technical College, tower over the factories and terraces of Harris Street.

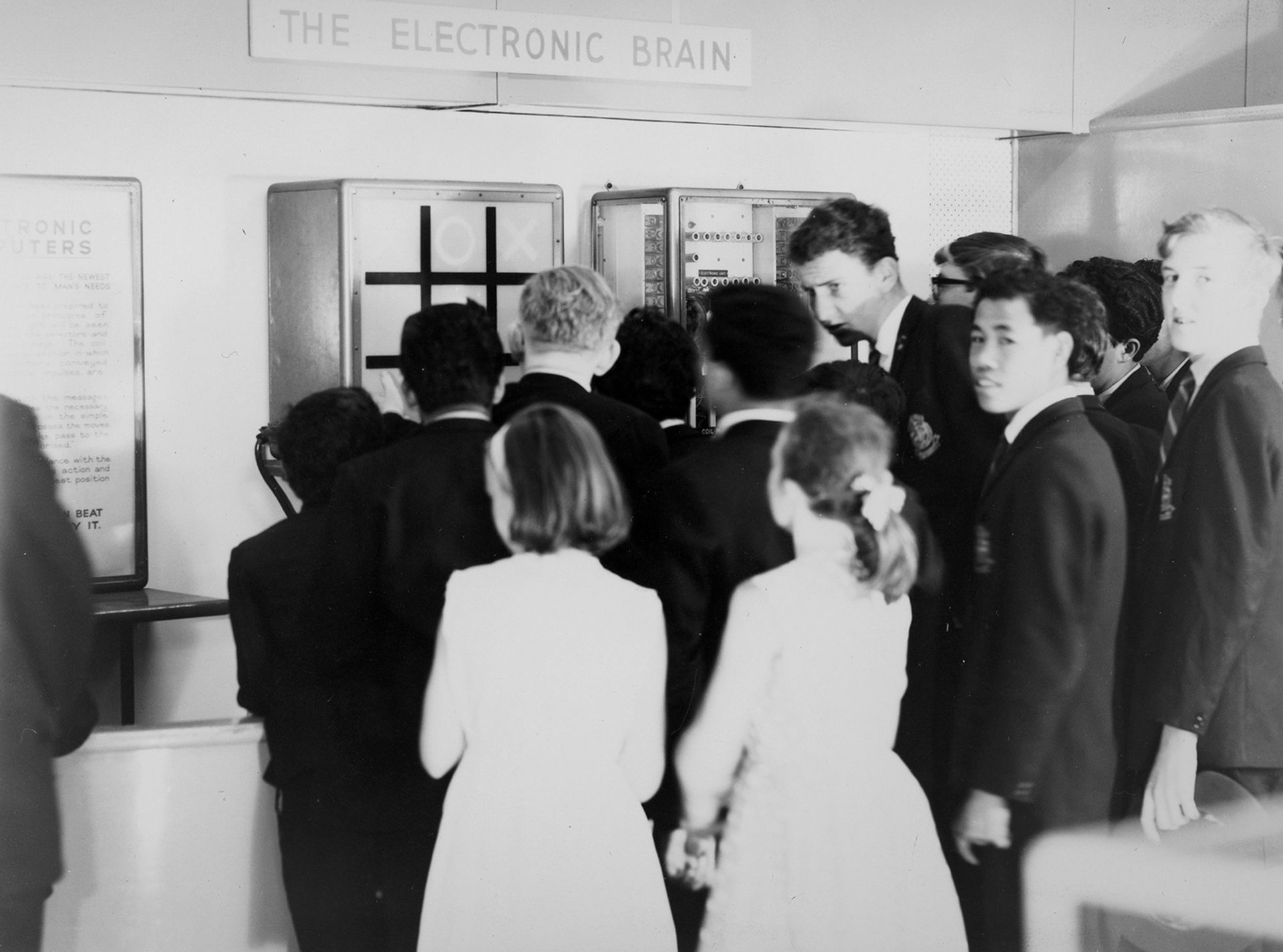

The Museum’s new home sees the revival of attendances from the early 1890s. ‘These were years of profound industrial and economic upheaval … The museum may have offered a sanctuary from the misery, social turmoil and division of the depression. Entry was free and the exhibits offered a way for people to pursue their interests independently of formal instruction.

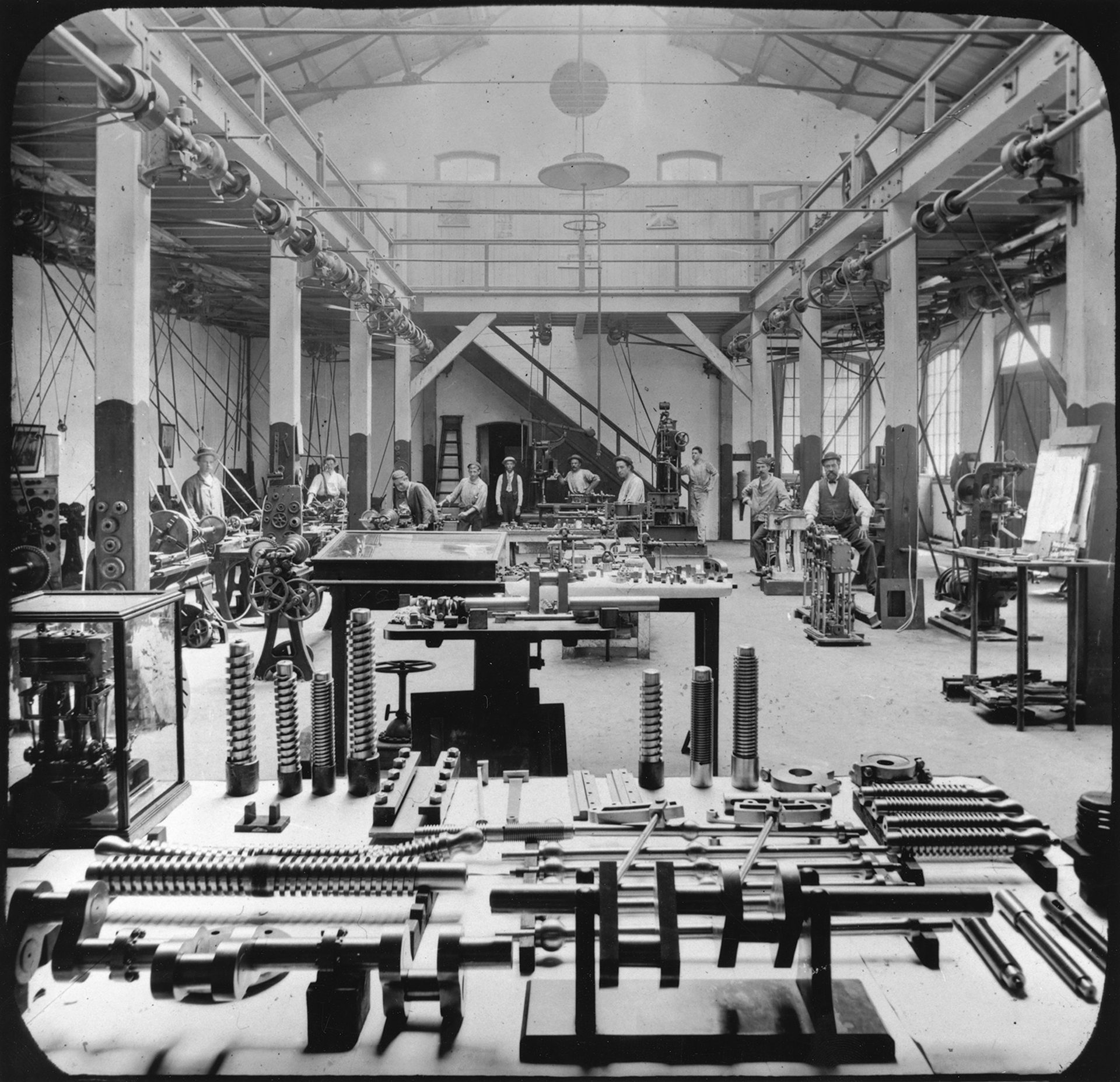

For the Working Man

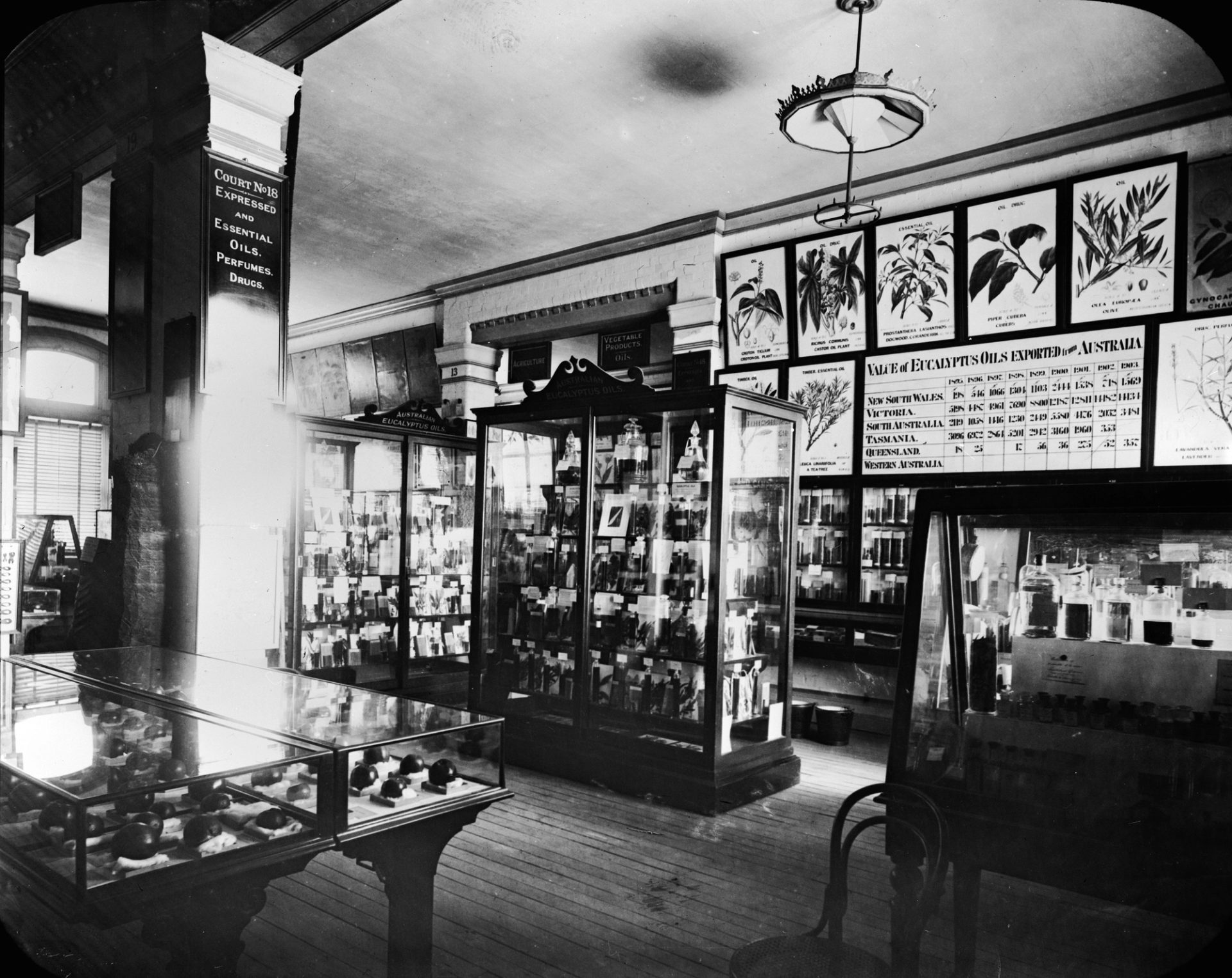

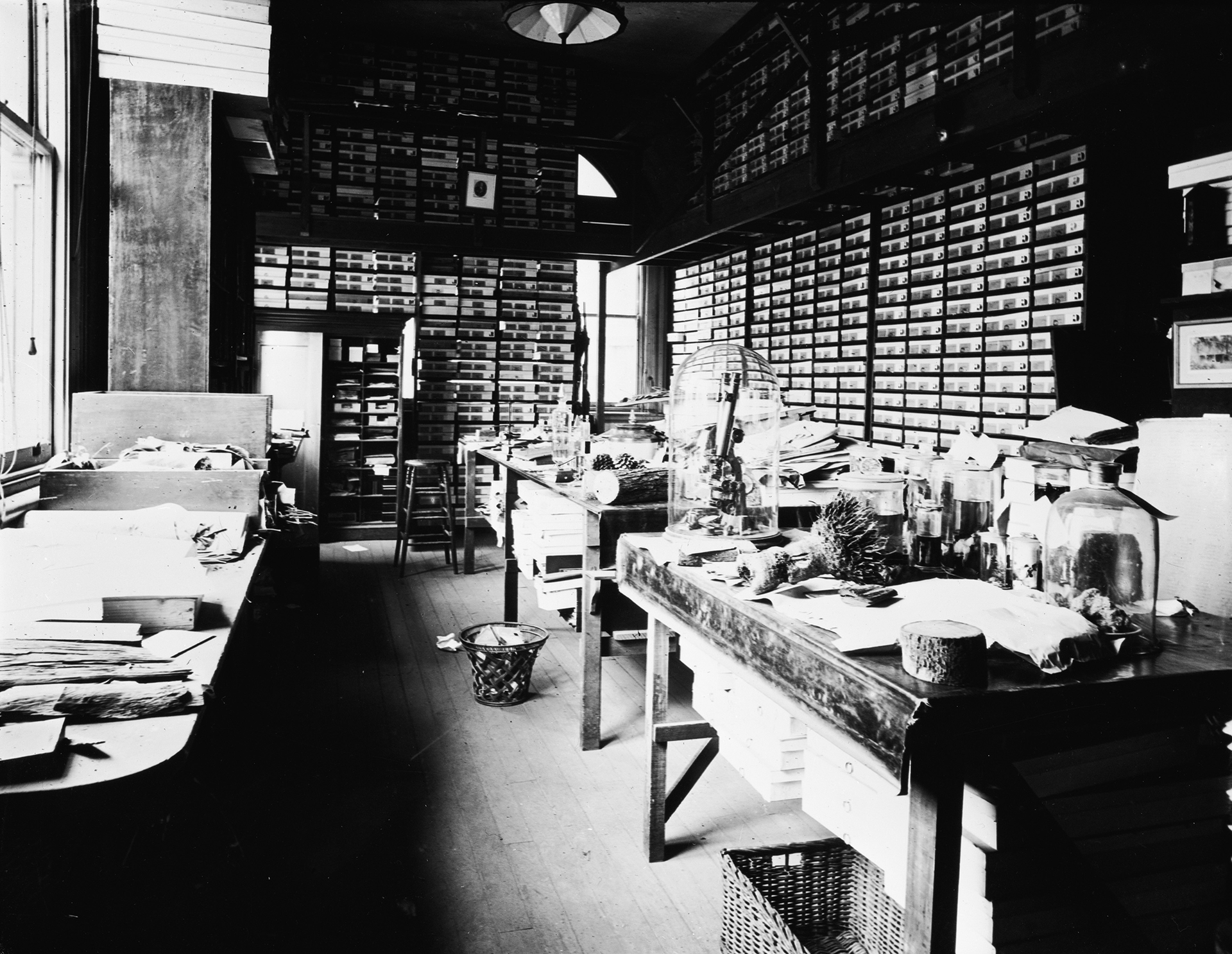

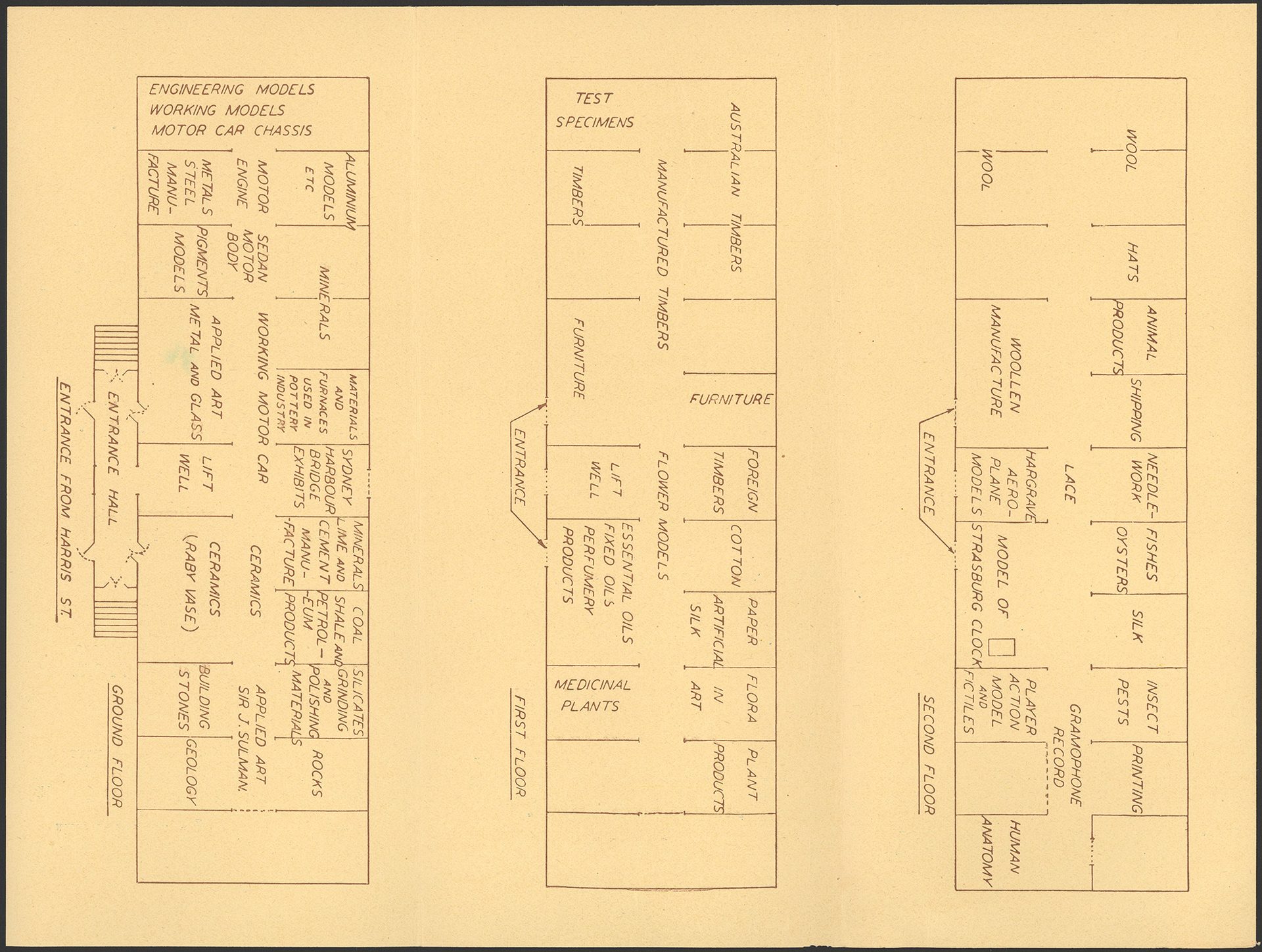

‘I have now been able to classify the exhibits in a way that has been previously impossible, and the contents of the old crowded building and the congested store show now to advantage, and cause surprise to most people, who had no idea of the extent and value of our collections.’

The Museum’s new home sees the revival of attendances from the early 1890s. ‘These were years of profound industrial and economic upheaval … The museum may have offered a sanctuary from the misery, social turmoil and division of the depression. Entry was free and the exhibits offered a way for people to pursue their interests independently of formal instruction.