A Corner of the Empire

One of Everything

‘It will be a huge storehouse in which will be found everything, from a needle to an anchor, figuratively speaking, and literally from a stable to a lucifer match’

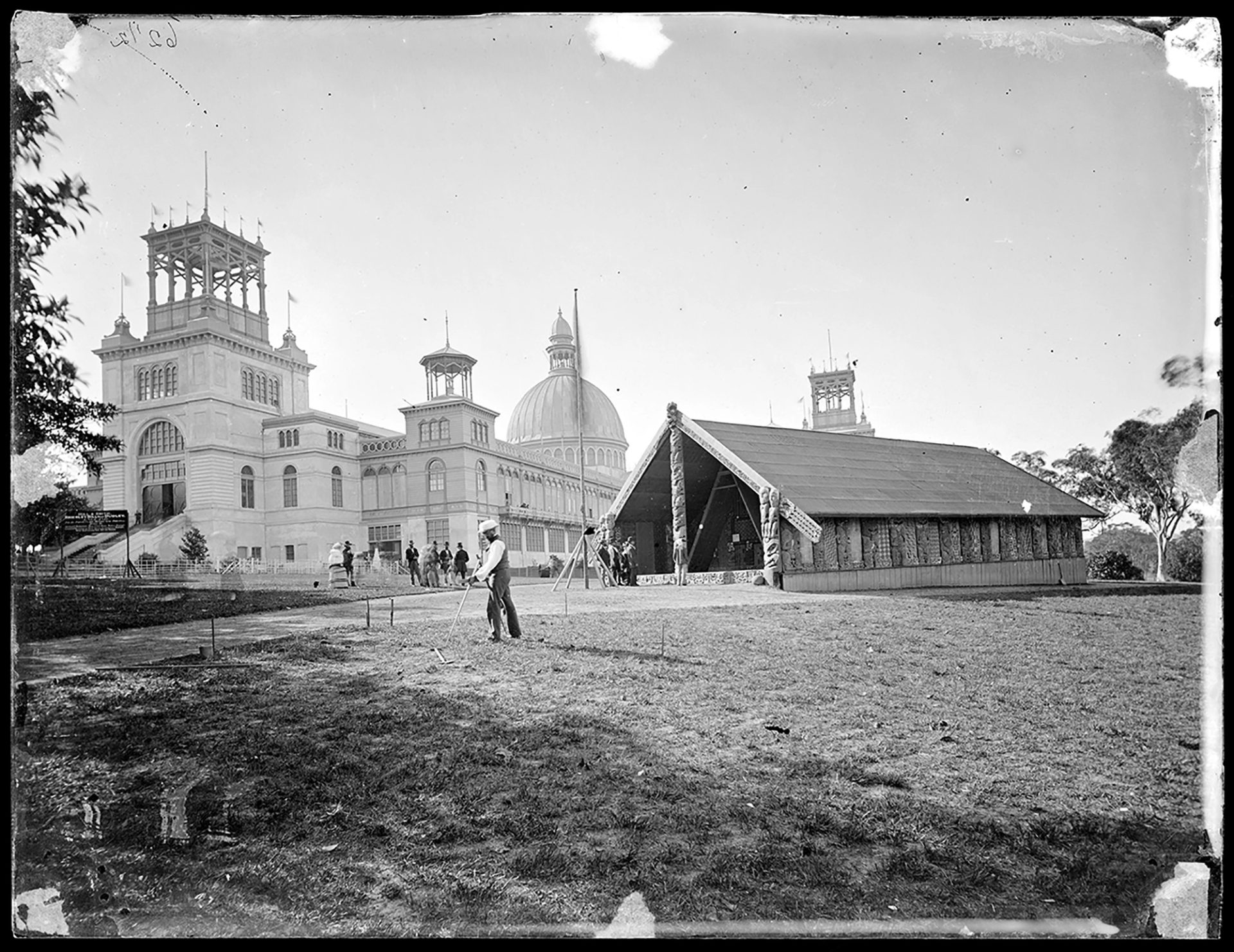

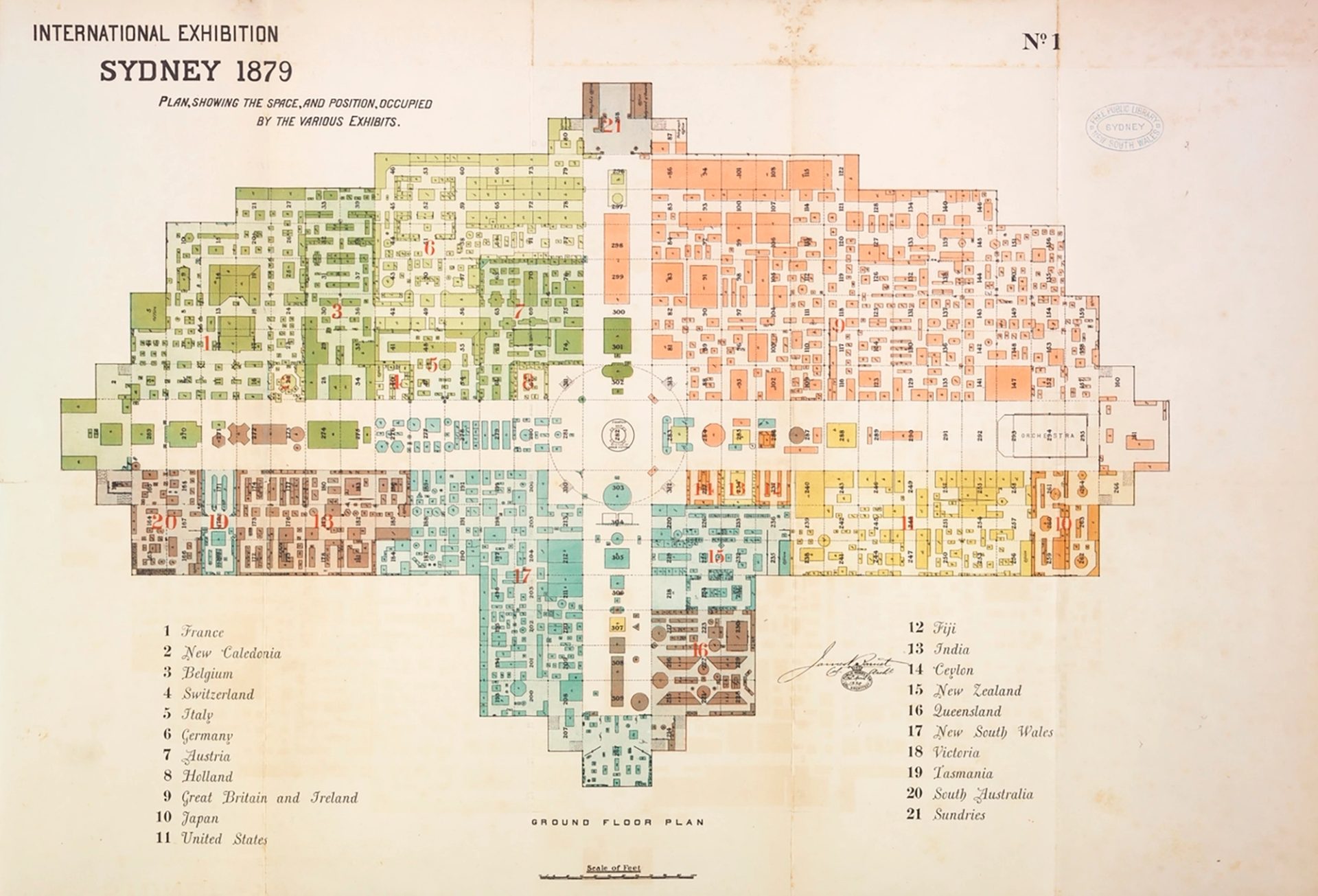

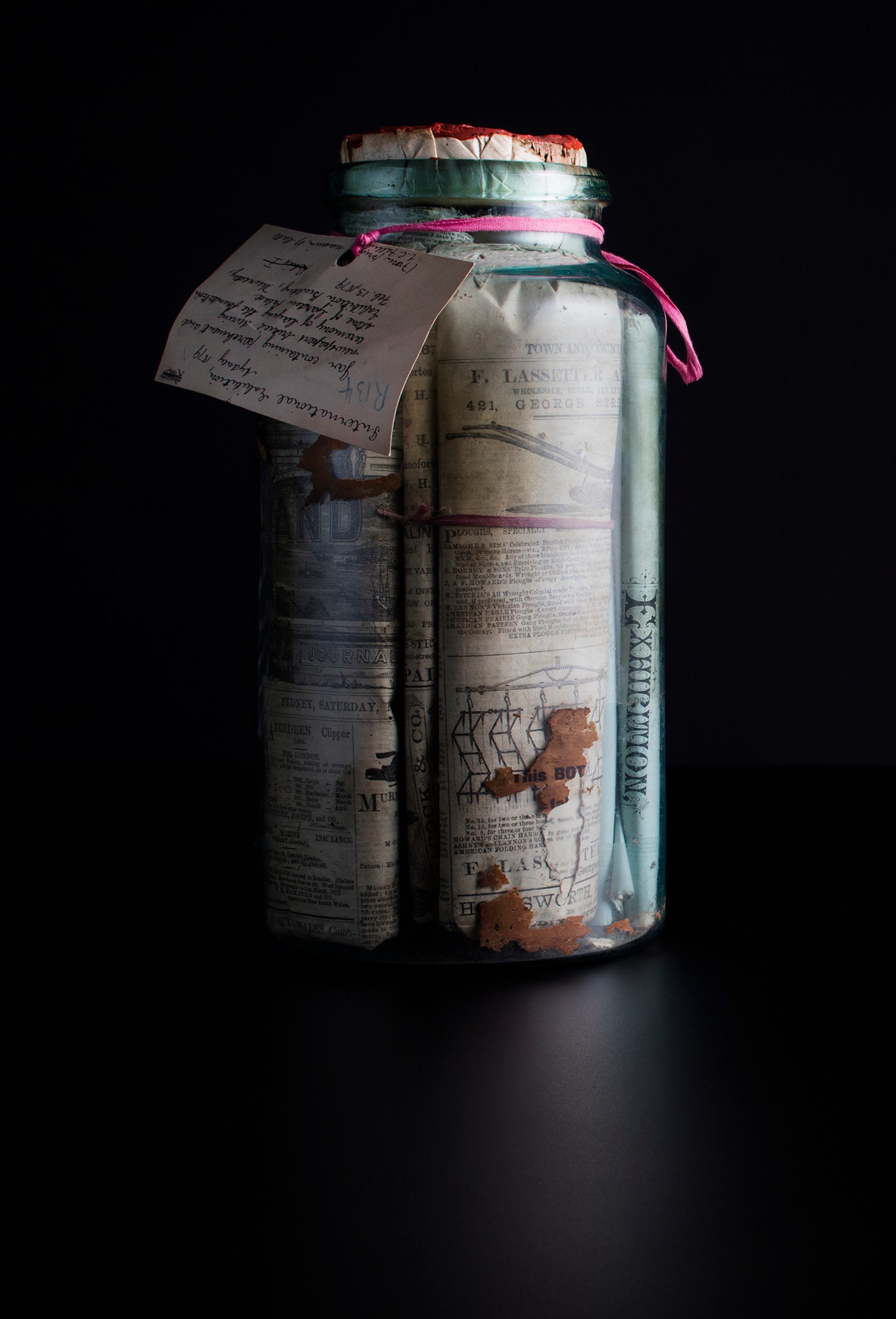

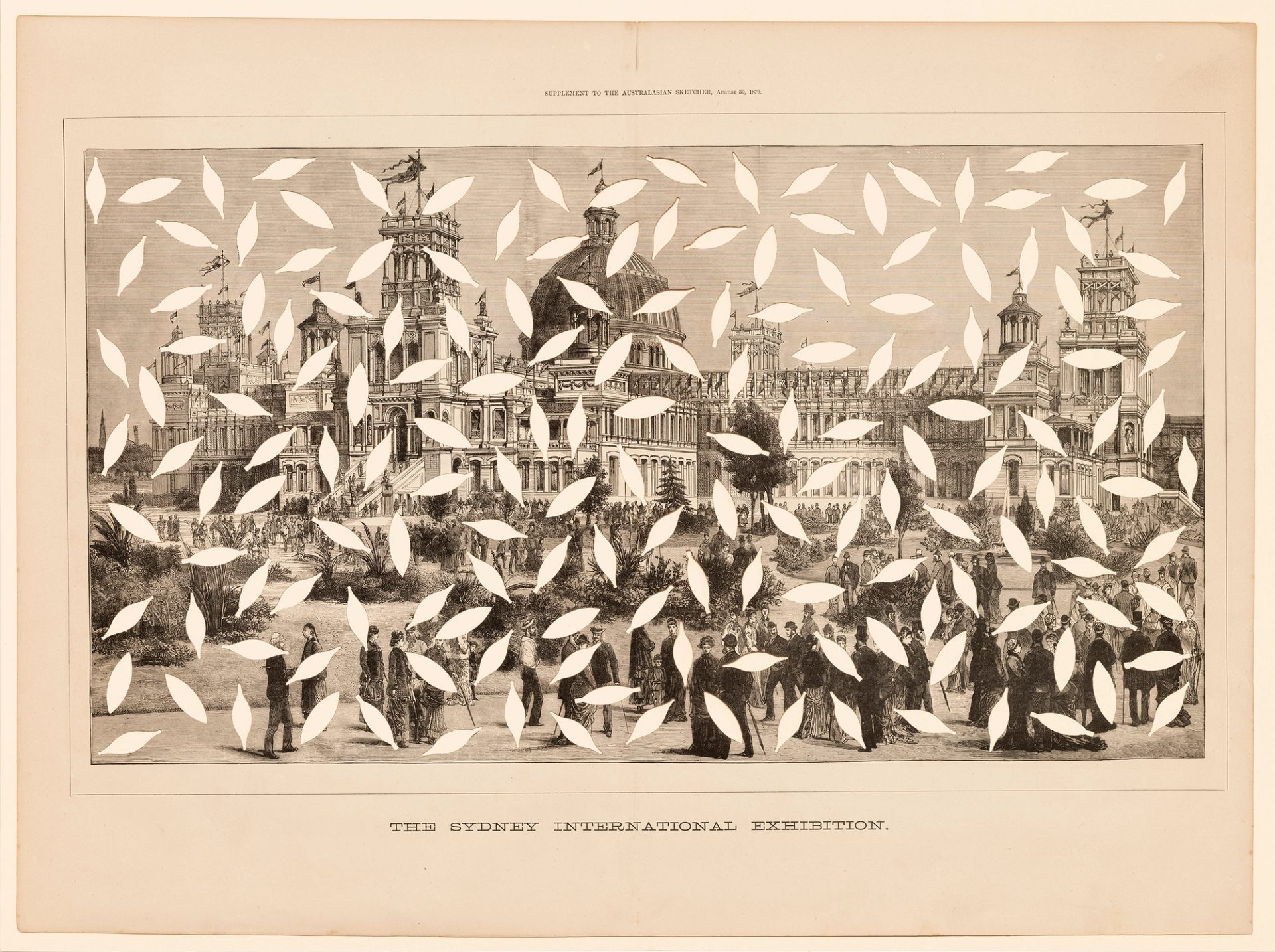

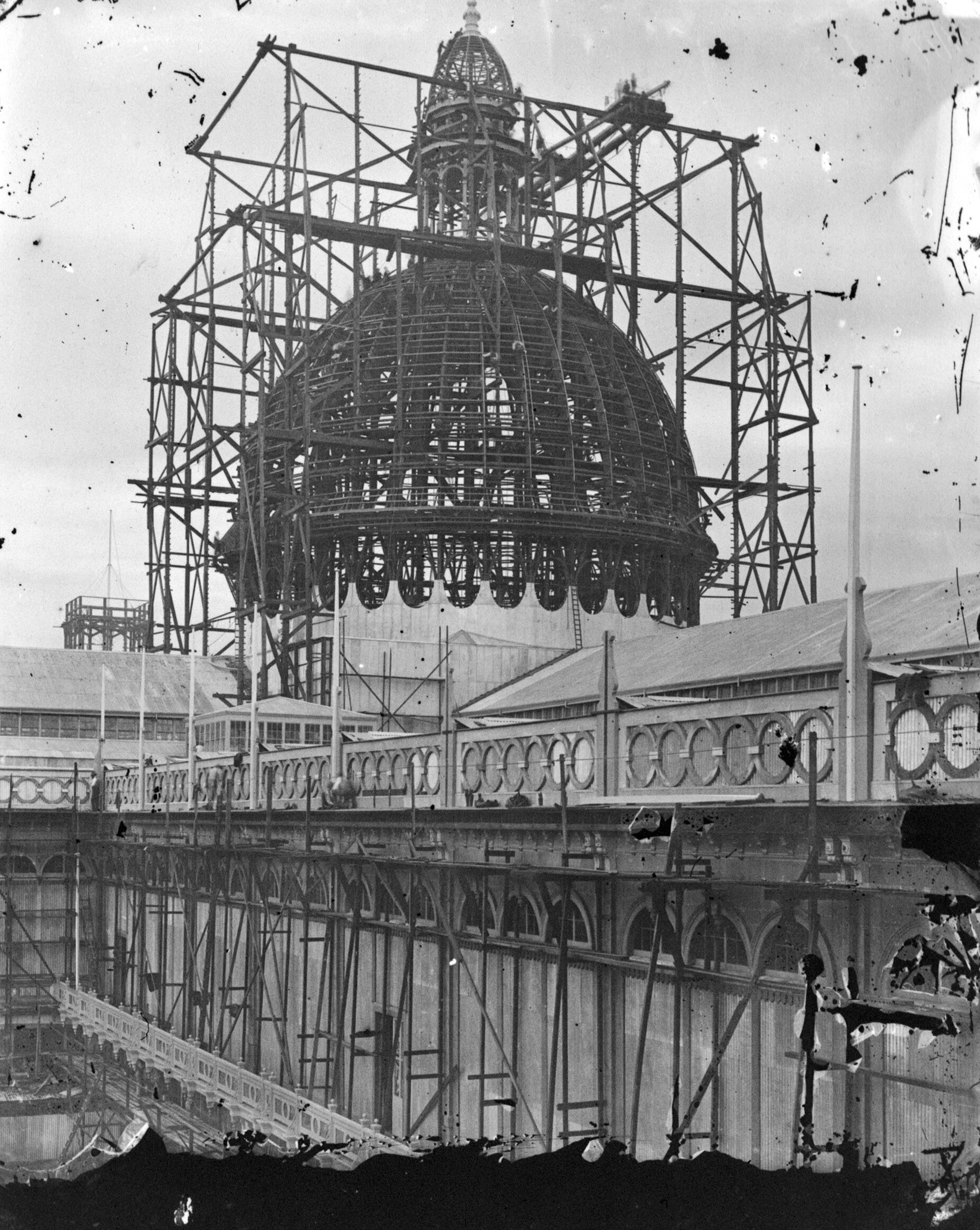

In August 1878, the Trustees of the Australian Museum unanimously support a motion to establish a separate Technological and Industrial Museum. One year later, the New South Wales government commits £500 for its formation. At the same time, the Garden Palace is built for the Sydney International Exhibition, held at the Royal Botanic Gardens between 17 September 1879 and 20 April 1880.

Designed by the colonial architect James Barnet, the Garden Palace is built in just eight months, the centrepiece for the Sydney International Exhibition.

Built primarily of wood, the Garden Palace contains a forest of posts supporting its mezzanine levels; vast tracks of fine-plank flooring run the 244 metre length of the hall. More than 4.5 million feet of timber are used — equivalent to 1370 kilometres.

The Exhibition Hall, arranged to echo London’s famous Crystal Palace, is designed to showcase the resources of New South Wales and its economic prosperity.