bala ga'lili

The two woodworkers, designers, artists and friends recount the establishment of the Dharpa Djäma Studio and the evolution of their Bala Ga’ Lili project and its ‘two ways learning’ philosophy.

Bonhula Yunupiŋu Before we met I was making things from dharpa, mostly gara and gaḻpu. That was the lifestyle we were living. It was handed down to us from our forefathers to our fathers and then to us.

Damien Wright I think when you showed me those spears and woomera you had made, for me that was the start of bala ga’ lili, that idea of things being transmitted and carried on, without beginning or end.

BY Meeting you took me to a different level. I had to work to get my hands around new tools. I was feeling uncomfortable at first but then seeing how you were using your machines and your tools reassured me and helped me.

DW You were my mentor. When we had a task to do you could see how that would work for all of the men in the workshop. It wasn’t just about getting the job done. It was also about Yolŋu culture and making sure that everyone had a role and was recognised. My focus had been on getting the job finished, but you were about making sure that everyone had a chance to learn and get a go.

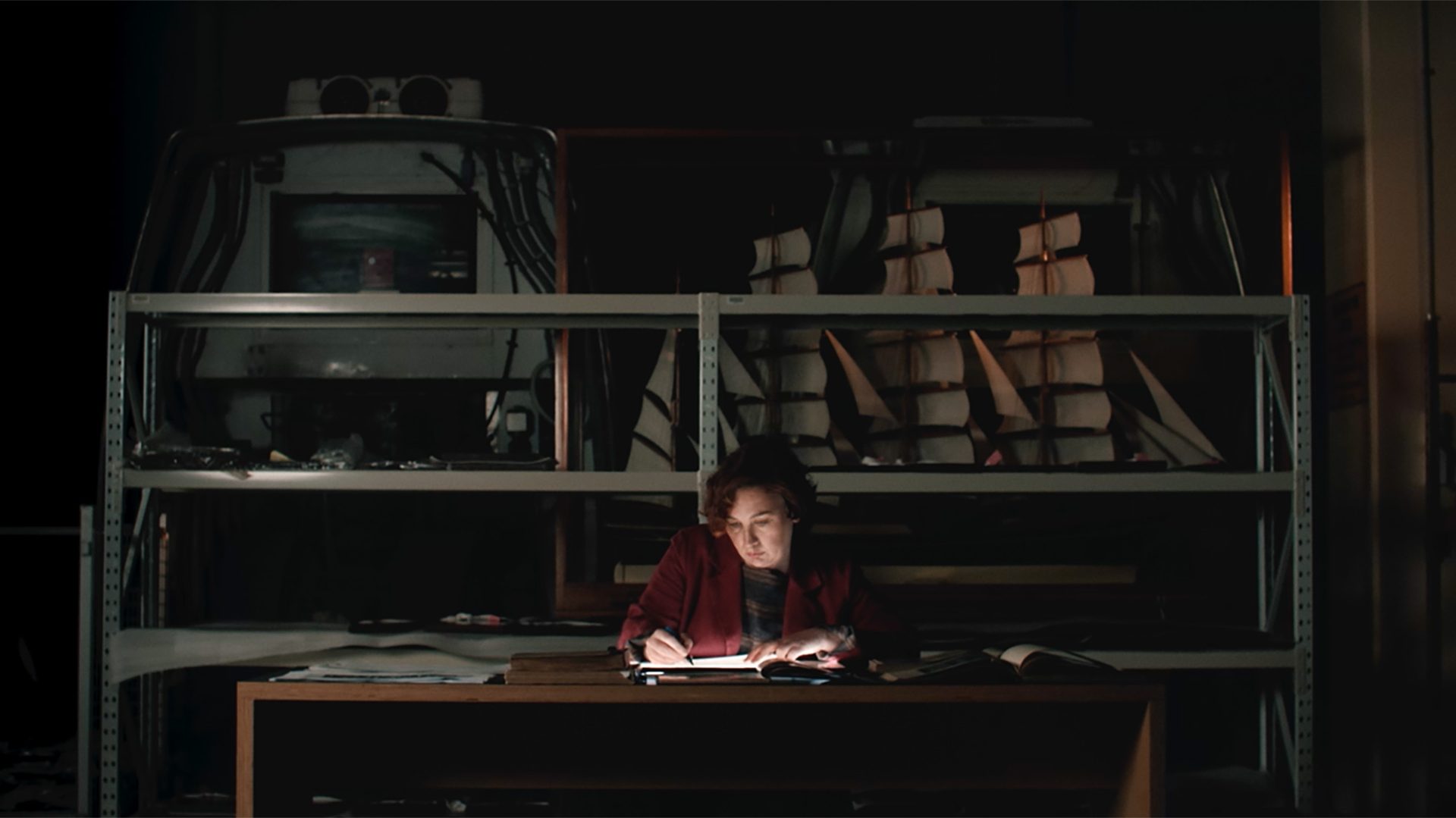

BY I remember the first project we did, the table in gaḏayka. It was like a new beginning for me, next level doing djäma with you. I didn’t know where it was going but you said, ‘Okay gäthu, I’ll show you’. You showed me how to measure and to use new tools and you said, ‘Stand on that side, I’ll stand on this side and we’ll do it together’. It was an amazing experience for me.

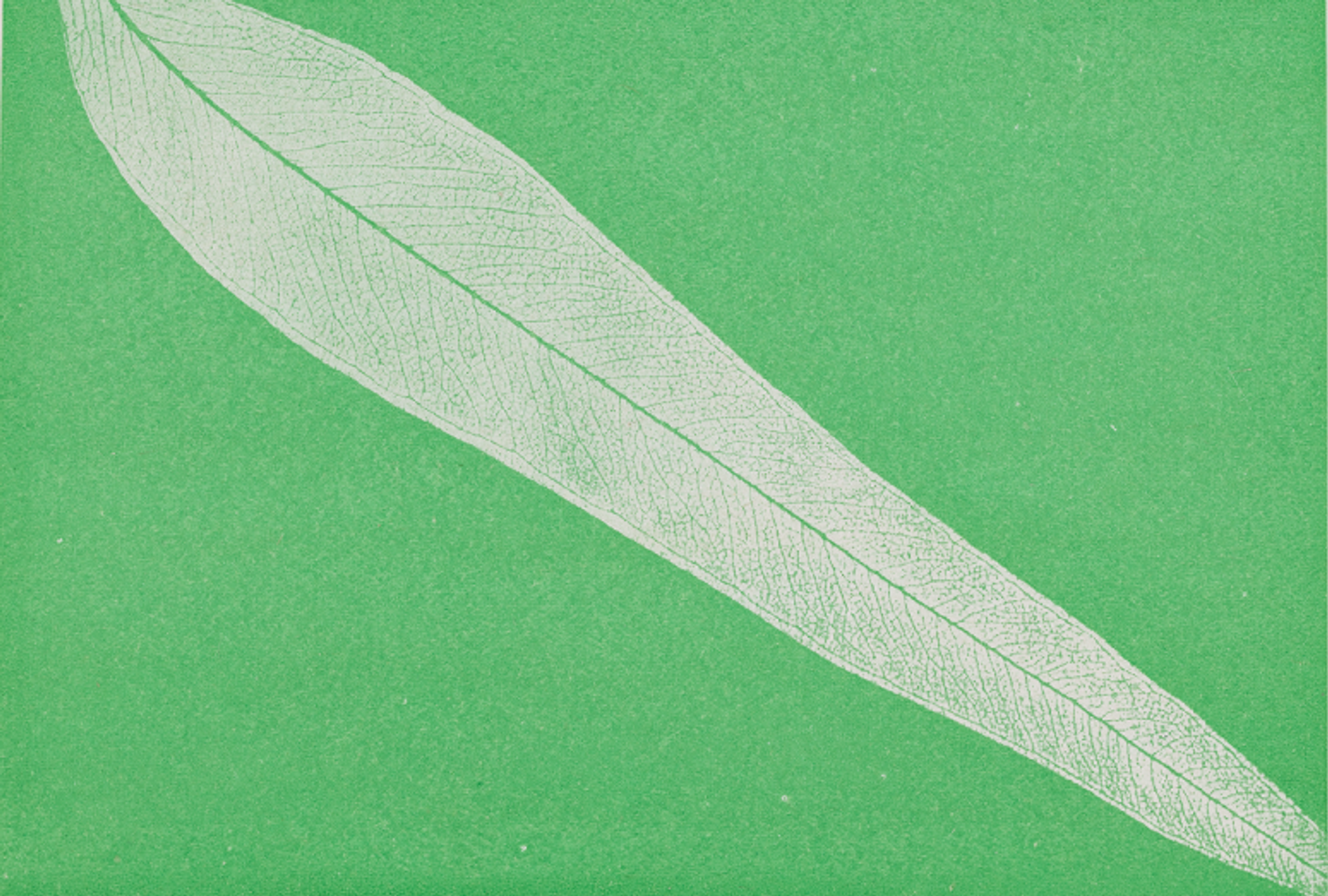

DW And for me too. I loved that you called me bäpa, father, and I called you gäthu, son. But the learning was definitely both ways. You taught me so much about the gaḏayka trees that are the main eucalyptus canopy across North East Arnhem Land.

You Balanda call it Darwin stringybark, and it is the timber we use for lots of things. [The late] Yunupiŋu wanted to prove it could be used as a furniture timber and that a furniture studio on Gumatj community could work. And he did.[He] saw a story in The Monthly about a bar table I’d designed and made for the County Koori Court carved from a massive slab of 10,000-year-old red gum. The idea that judges no longer sat on high, but were gathered with lawyers, Elders and defendants on the same level to listen and negotiate. [Yunupiŋu] came to visit me, to invite me on Country.And so I travelled the 5000 kilometres from Melbourne to Nhulunbuy and, over two weeks, we made a table. To the dance, smoke and song of ceremony, you, Djalong Yunupiŋu, Brian Gurruwiwi, Tony Munuŋgurr, Russell Gurruwiwi and I made a table. The table pleased [Yunupiŋu], and he asked me to return to run a woodworking workshop.