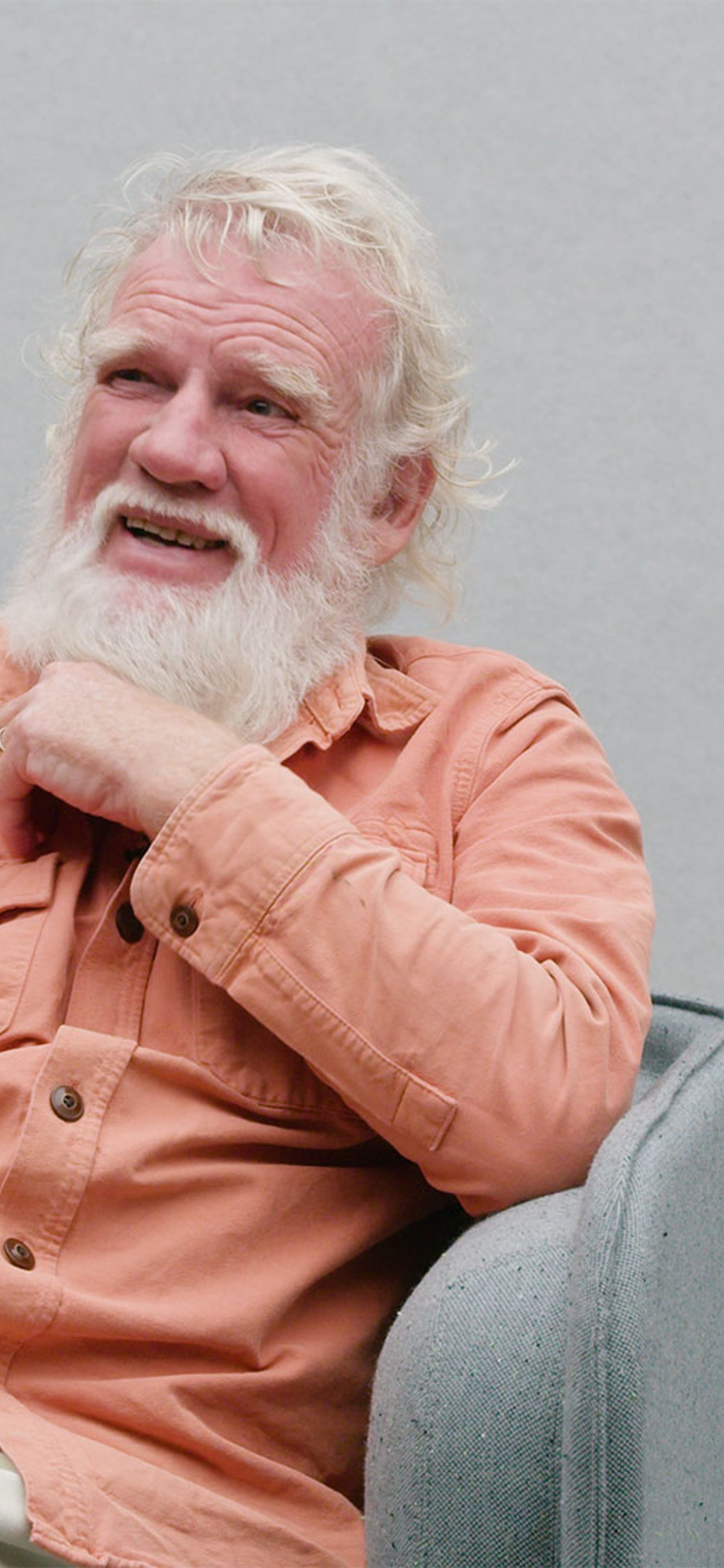

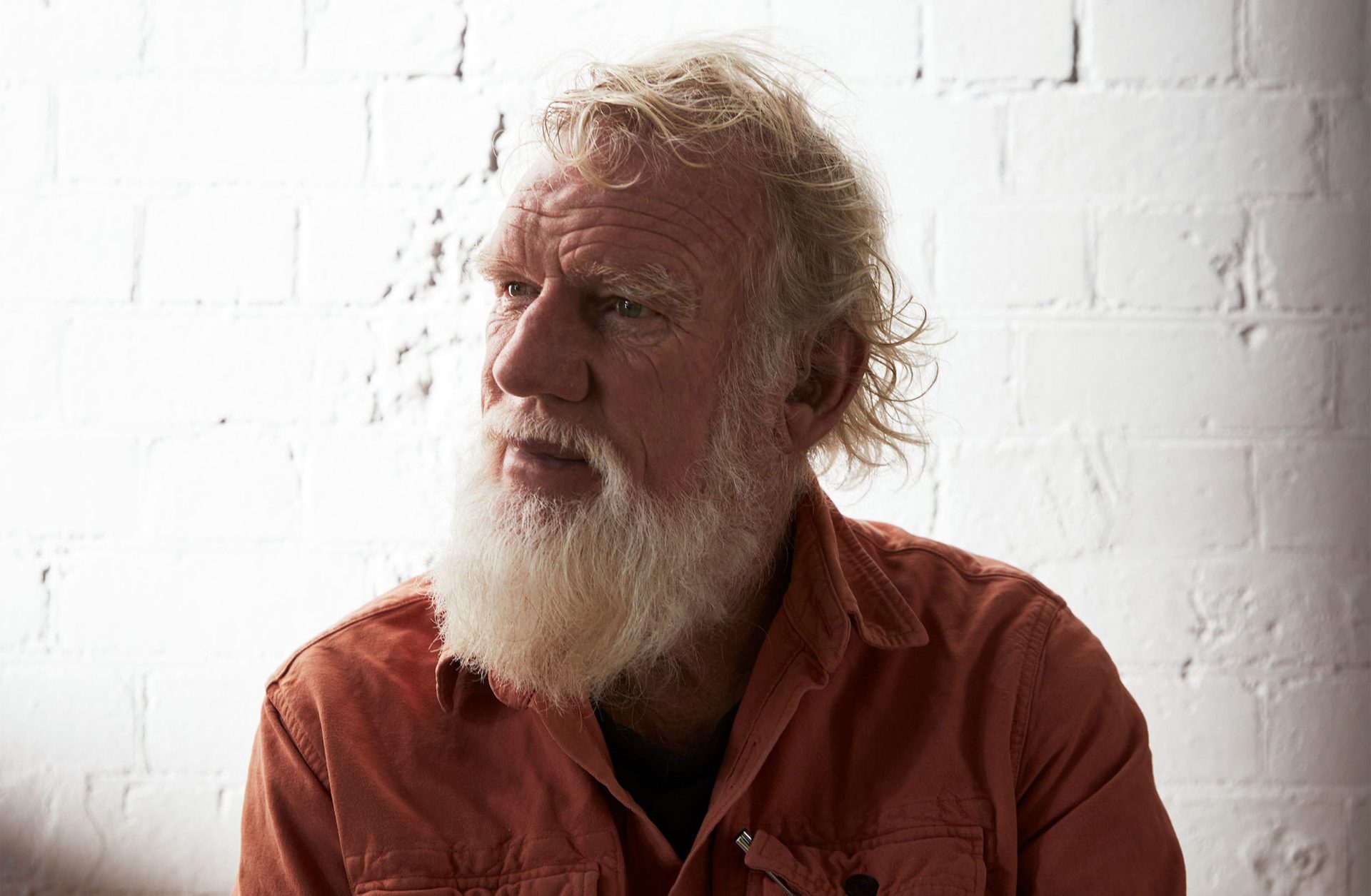

CR

Let’s look to the future. Ten, twenty years from now, what will we see, what will we eat on our tables? What will have changed? How will it have changed the way we consume food and create it?

BP

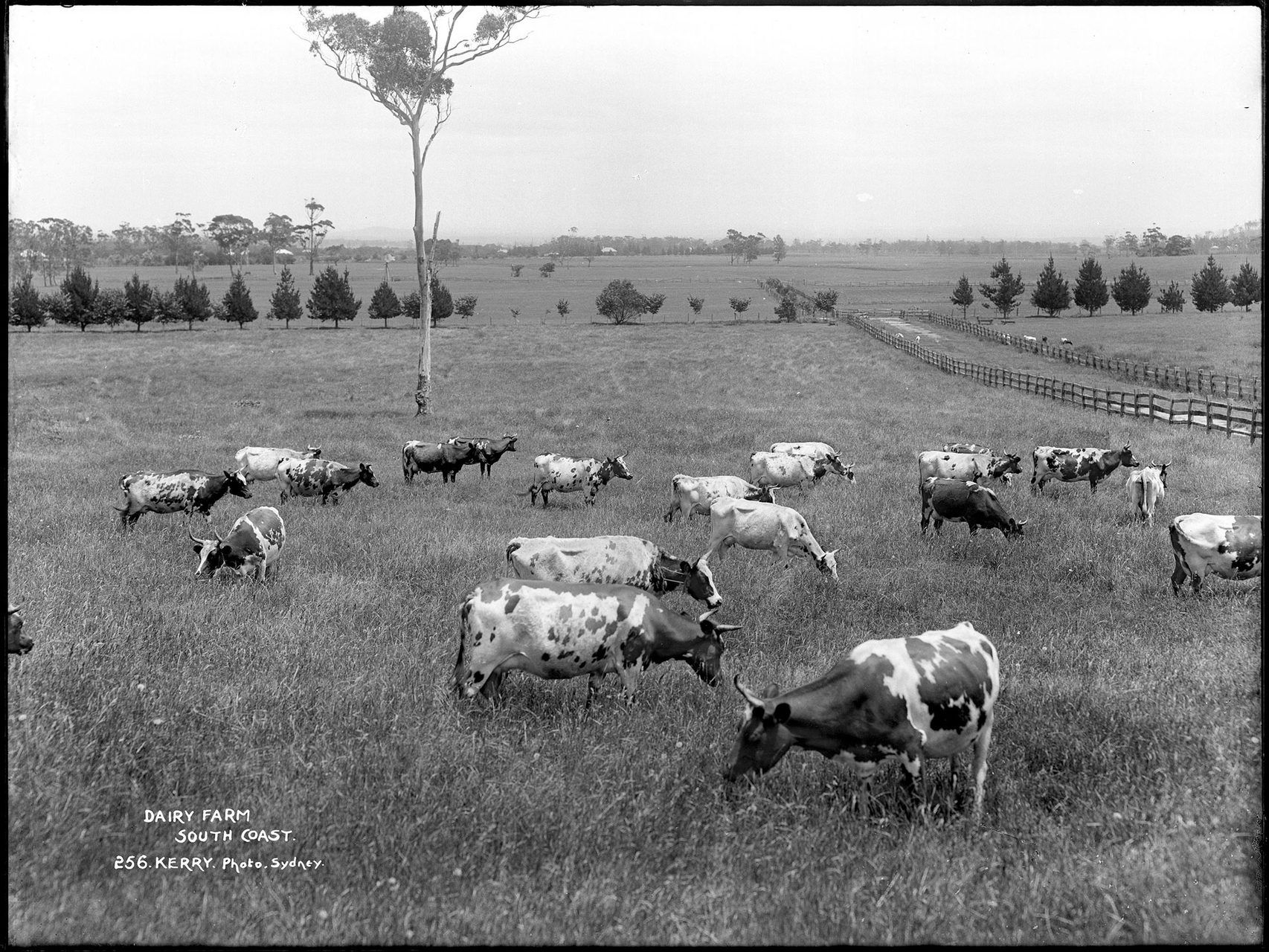

Well, because unless we do something about population there’ll be less ground for people, so we’ll be eating a lot more salad vegetables. So, we’ll be eating salad greens, those mixed salads are so easy to grow. We’ll be growing those, but I hope we’ll also be growing cunjim winyu which is a one of our salad vegetables that grows in saltwater. This is a plant that’s going to be very useful for the world. The old people obviously utilise it, it’s very beautiful. Chop up half a dozen raw vanilla lilies into that, have a tomato if you have to and a fish and that’ll be great. We need to get rid of our hard-hoofed herds around the world. We all need to eat less meat and I’m a great carnivore, if I don’t have meat in the meal, I feel like I haven’t been fed. I’m old fashioned, I am trying to change but our ideal meal in Australia will probably be a salad with a fish or something like that.

CR

It’s funny, as we as we look at $12 iceberg lettuces, it seems that if we’ve got these things that can be built, we can grow leaves in salt water, it seems like to make so much more sense to be doing that and using traditional approaches.

BP

Well, those old people again looked around and tasted everything and said, ‘Oh well, we’ll look after this one because we can eat that.’ But every plant had its use. But for food, there was a lot of testing going on because kangaroo grass is really difficult to harvest and process. The old people did it for a reason and its gut health. Kangaroo grass has this incredible interaction with your gut and it’s because of the, I don’t understand the science of it, but the biota around the seed is so interactive with our guts that the old people would have noticed that, you get to see a fair bit in 120,000 years and remember stuff because you don’t get interrupted by bombs, when you’re not being bombed, you can concentrate. So that’s what those old people were doing in that great time of peace, they were looking at things like gut health.

I know it sounds like a gilded romance but the more I look back at it, the more I think, ‘You can’t last that long without having really thought it through.’ Not just things like food, but how to handle the human instinct, how to handle the human animal. Because we’re just humans, we wake up cranky, we wake up kind, we wake up selfish and mean and jealous. Just people, that’s the human animal. But how do you how do you govern that animal? And those in that great time of peace, which was created by governance, the people had the time to think, if we’re going to eat this kangaroo grass, how are we going to distribute it? How are we going to harvest it? How are we going to look after making sure that plant is always there? Or if it’s not there because of climate change – this is why I’m bit excited today because science, 40 years after we asked for it, has found that the old Aboriginal mounds where a cumbungi or bulrush was processed because of a climatic event.

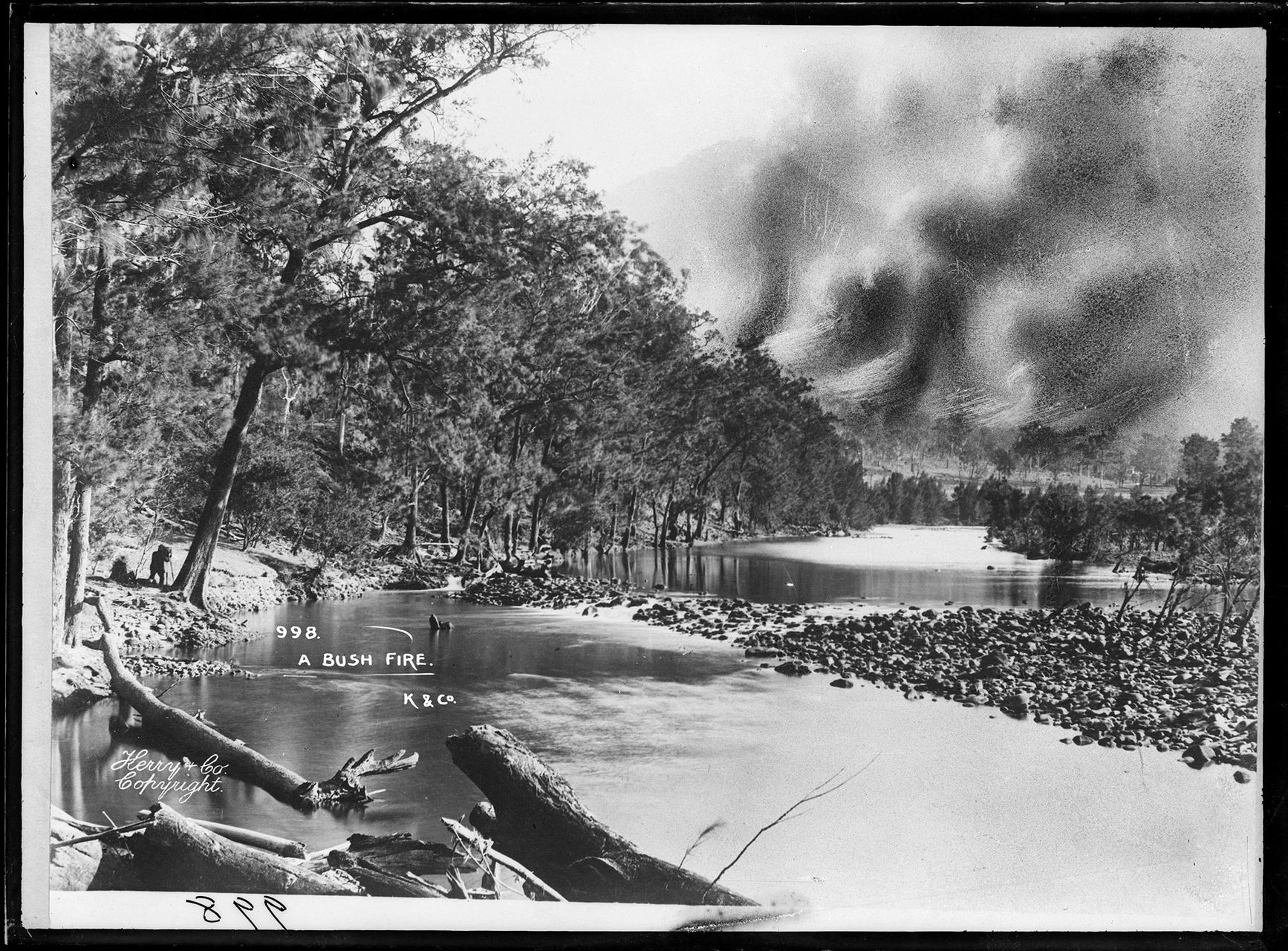

Suddenly Aboriginal people found that foods that they had been reliant on were no longer available because of drying of the continent. So, they turned to cumbungi which would grow in the low lying, wet areas and learnt to process that. It’s probably only 5 or 6000 years ago, maybe longer, some are saying 40,000. But it was a change, so we have to be flexible and ready to change and use whatever mother can give us and not get stuck. ‘We’ve got to have wheat, we’ve got to have wheat, we’ve got to have wheat.’ Mother’s not giving us wheat today, what are we going to do? And working with the energy, the engine of Mother Earth and not against her. Not demanding, ‘Mum, you’ve said we were going to have wheat forever’, ‘No, I didn’t.’ We’ve just got to be really flexible and kind, kind to the Earth.

CR

Bruce, what I love about talking to you is that we’re talking about taking on these challenges that we’re facing, like climate change and changes in our climate. But you are always looking back to Aboriginal history, into the past to find the solutions and try to bring them to us now. And I love seeing that and I hope that in the future we are eating the food that you are learning about. I hope we are supporting Indigenous communities through that as well, and I hope that this dream of yours has become a bigger dream. Thank you so much for sharing your knowledge and your thoughts. Please thank Bruce Pascoe, ladies and gentlemen.