Right of Reply

overview

In ‘Right of Reply’, inaugural Powerhouse Director of First Nations, Emily McDaniel, reflects on the evolving relationship between Powerhouse and First Nations peoples.

‘I think often about the earliest inception of the museum we know today as Powerhouse. I wonder what might have been going on inside the minds of the founding committee members when they first convened in 1880. I dare say that if they ever projected their imaginations forward to today they would not have conceived of First Nations leadership at the museum.’

Indigenous peoples were perceived to be a momentary presence upon the landscape, diminishing with each generation until we would be consigned to a memory of the past. The inception of this institution and its early practices were driven by a vision of trade, industry and economic growth for the future of the colony. It was a future we were not imagined to be a part of. This museum was not created for First Nations peoples; its structure and practice never intended to benefit us.

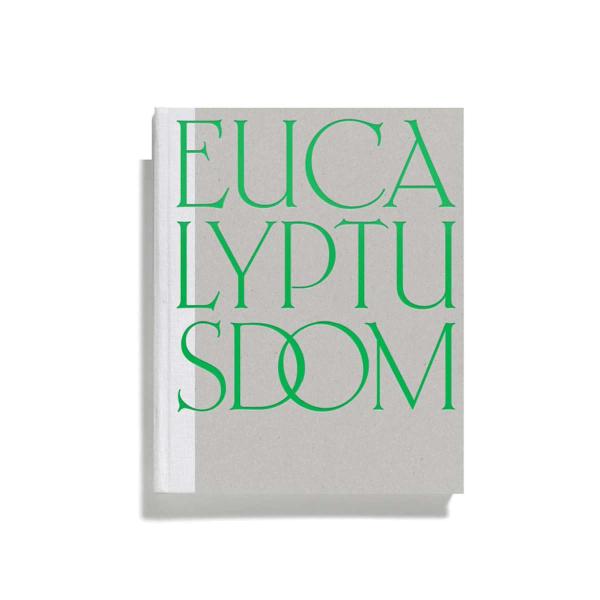

I was appointed the inaugural Powerhouse Director First Nations in August 2021, having joined the organisation earlier that year as one of four curators on Eucalyptusdom – an exhibition that did not enshrine the collecting practices of the past, but rather mapped the failure of foresight by the museum's forebears. The project's development process served as a diagnostic tool, ushering in the beginning of a better institutional understanding of the illness created historically through a wilful omission of First Nations representation. It coincided with the establishment of the Powerhouse First Nations Directorate, signalling a self-determined future and direction for First Nations engagement and representation.

Within the Eucalyptusdom curatorial team, I was tasked particularly with consideration of how this museum's relationship with, exploitation of, and narrative surrounding the eucalypt implicated or included First Nations people. Like most cultural institutions, it is as telling what the Powerhouse Collection excludes as what it includes. Countless oils, vials of kino, sheets of pulped paper, thousands of wood samples, turned-timber pedestals and furniture, pianos, sledges and pipes made of eucalypt hardwoods told an expansive narrative of industry, expansion, exploitation and deforestation. Among it all, our absence — the lack of our stories, memories, knowledge and objects absolutely glaring.That void left us with a curatorial provocation: how to make an exhibition in response to the collection when its narrative is a history of exclusion?