Chella Man – The Device That Turned Me Into A Cyborg Was Born The Same Year I Was

‘I want to convey how I experience the world, and share how deaf individuals live on this ginormous continuum. I’ve always been in between the hearing world and the deaf world, but at this point I’m discarding that – I’m not between anything, I’m in my own world’

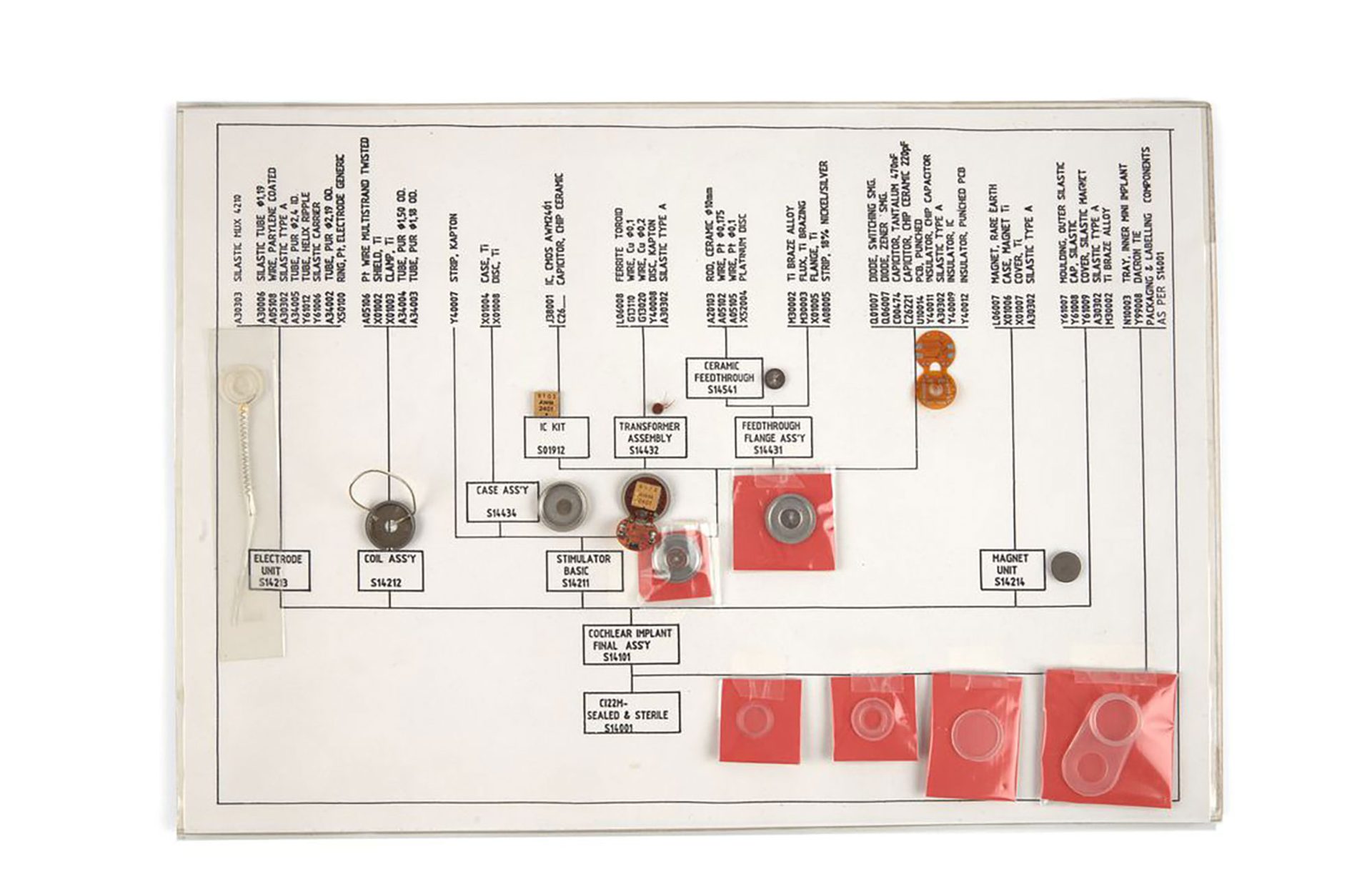

The arrival of the first cochlear implant was deemed a major feat of science for inviting the deaf community into the hearing world. Yet, within debates surrounding deafness and matters of identity, the dialogue around it has become fraught with conflicting opinions – a device considered an ableist development by some, and crucial to communication to others.

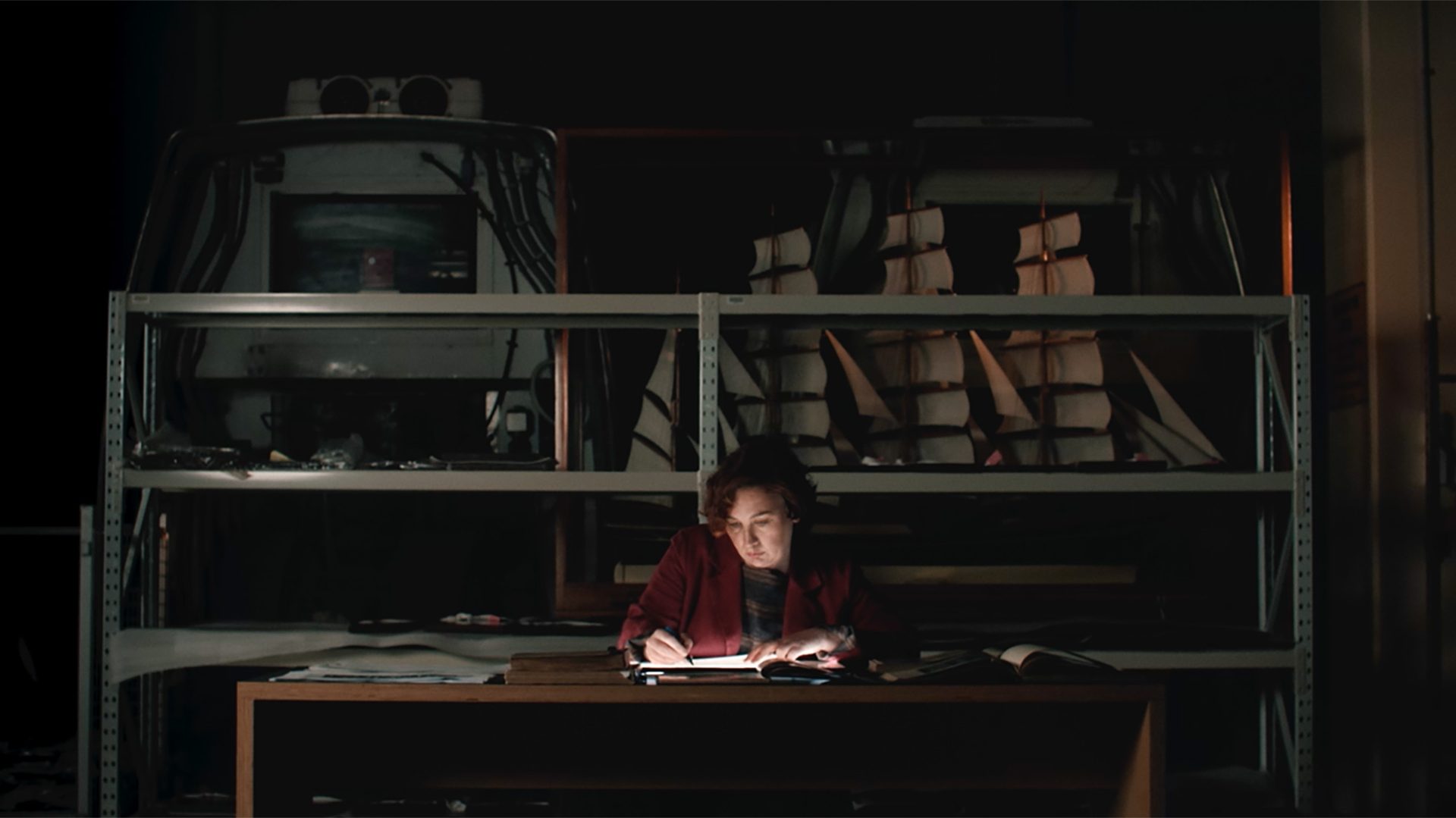

Co-commissioned by Powerhouse and Nowness, The Device That Turned Me Into A Cyborg Was Born The Same Year I Was is a short film that explores actor and director Chella Man’s relationship with the cochlear implant, and the nuances of life on a continuum between the deaf and hearing worlds. Fed by his experiences as a deaf, transgender, gender-queer creative, the film traces the journey through to his strengthened understanding of identity, and the multiple social convergence points he has been forced to navigate as a result.

Objects from the Powerhouse collection are animated through stories told by those who have the most intimate and personal relationships to them. Home to Dr Graeme Clark’s ‘gold box’ cochlear implant prototype and its subsequent developments, the collection also houses complex contradictions that exist between science, disability and identity. Debating the constraints of machinery, The Device That Turned Me Into A Cyborg Was Born The Same Year I Was investigates these tensions through the immobilising feeling of living and breathing as a cyborg.