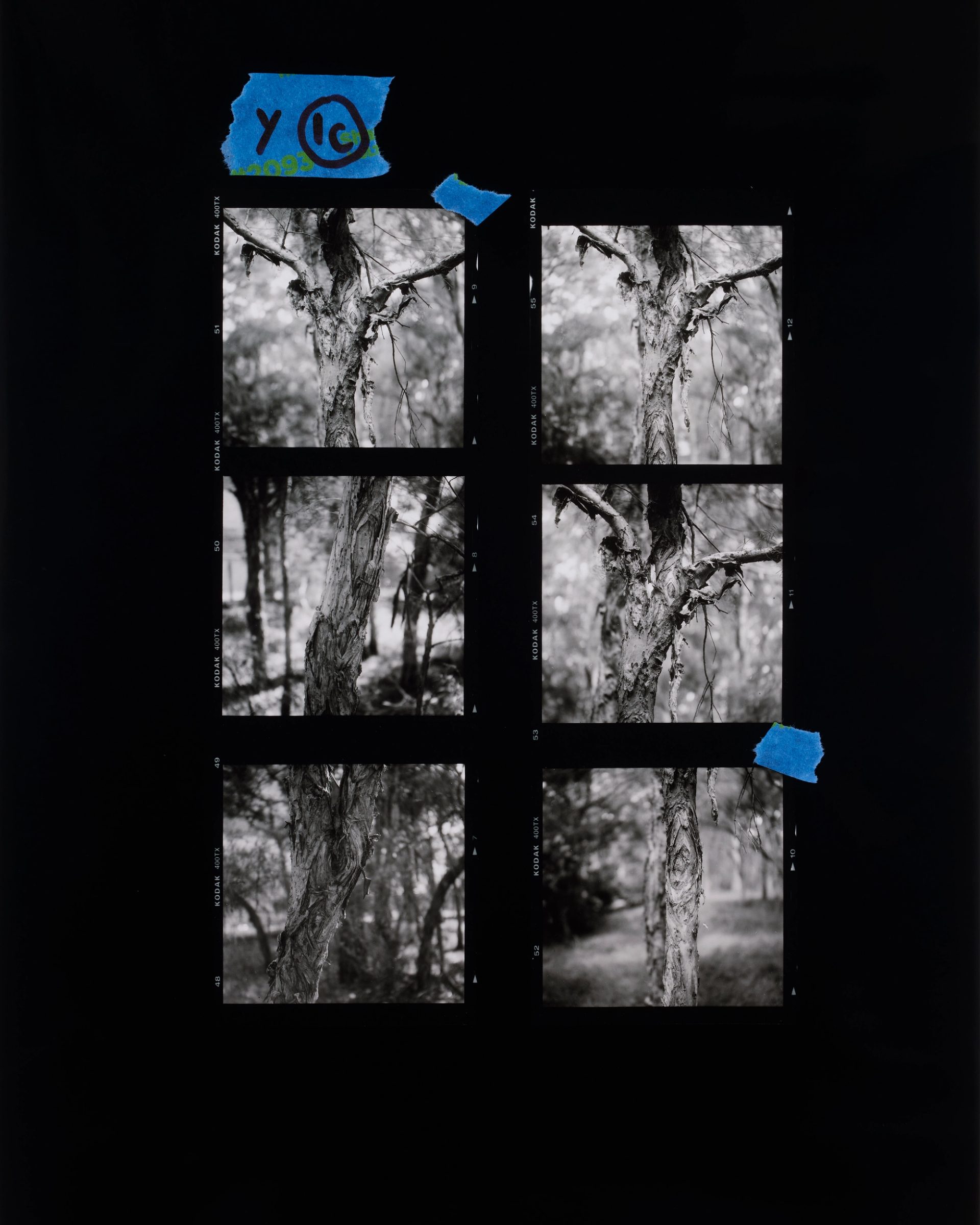

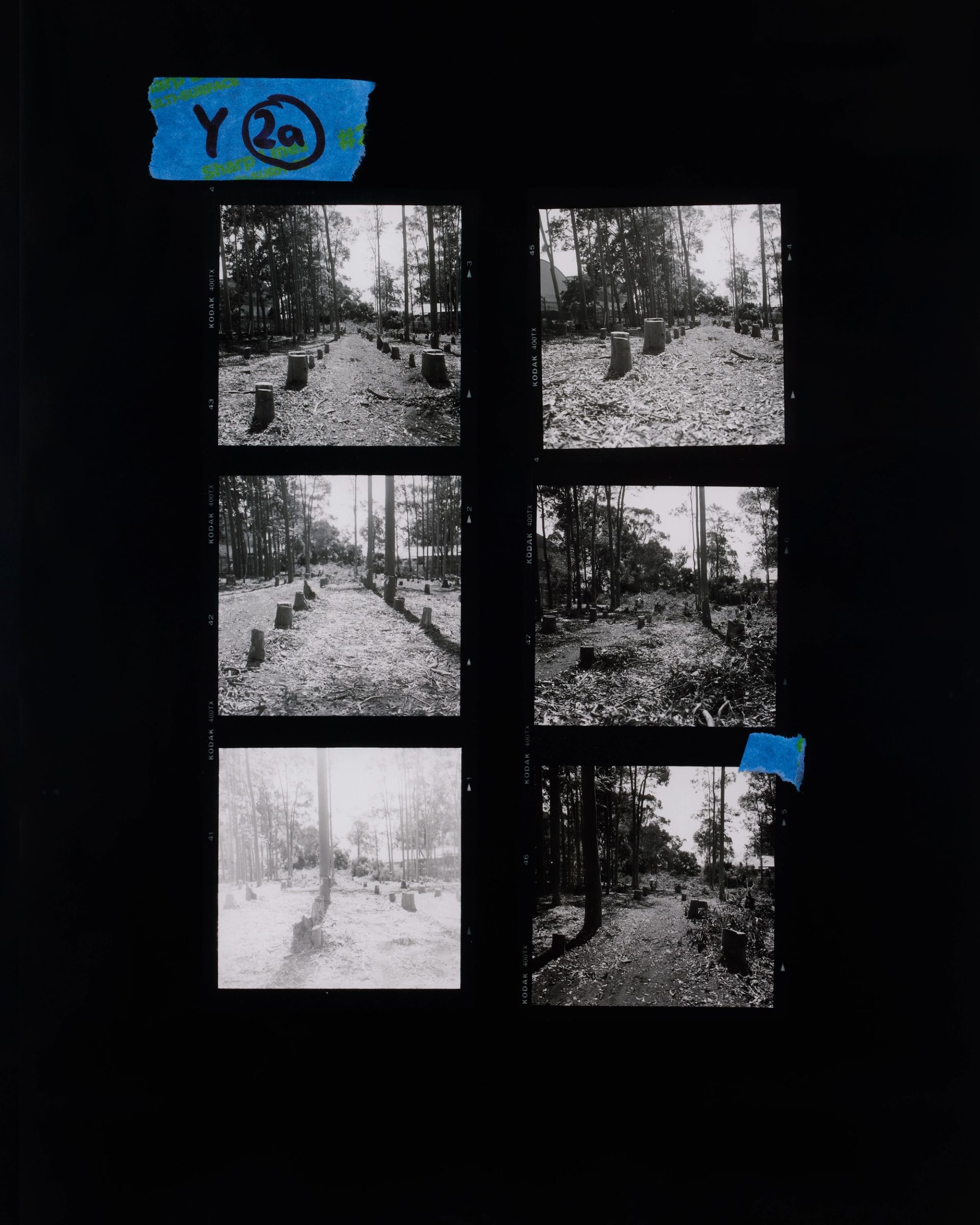

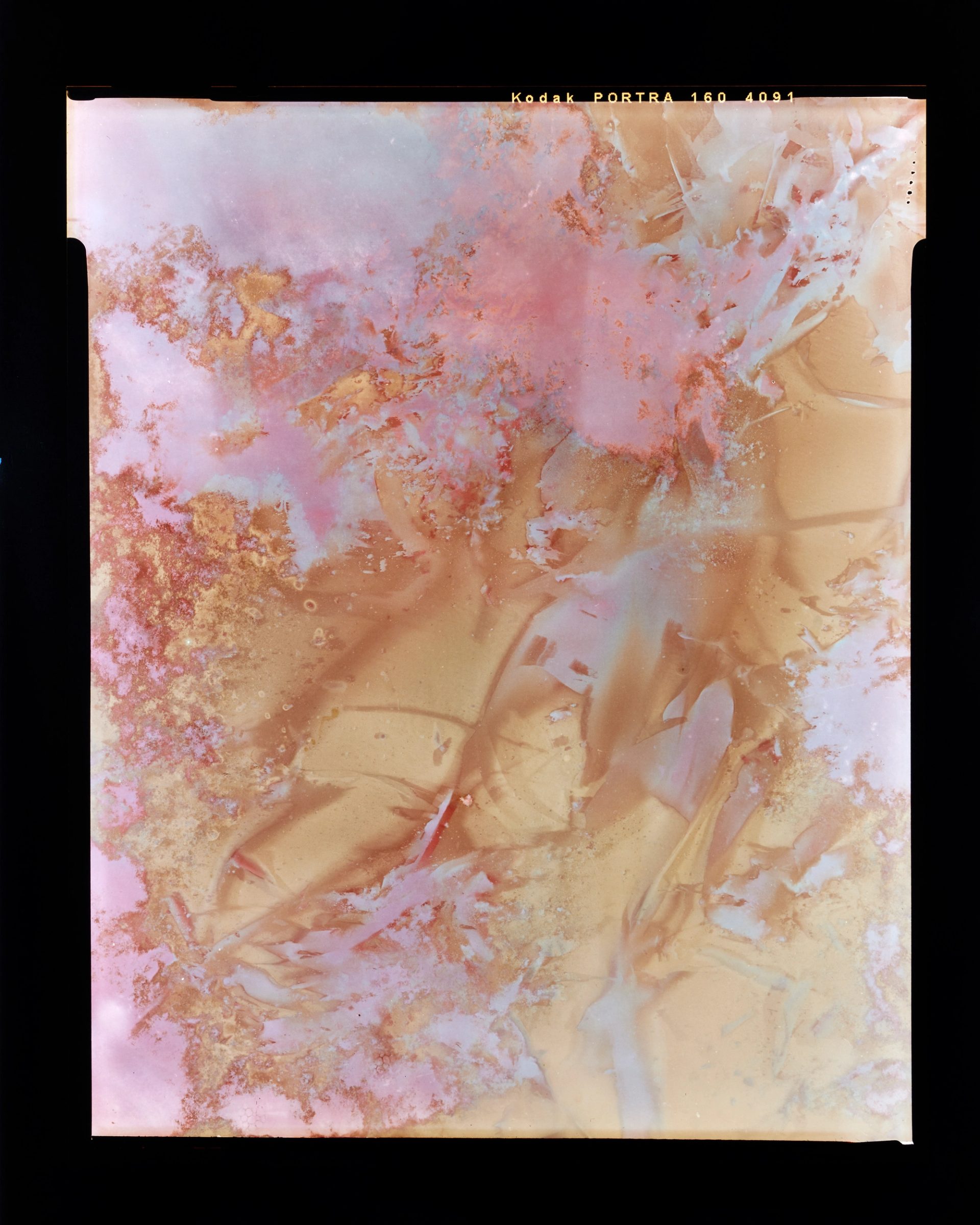

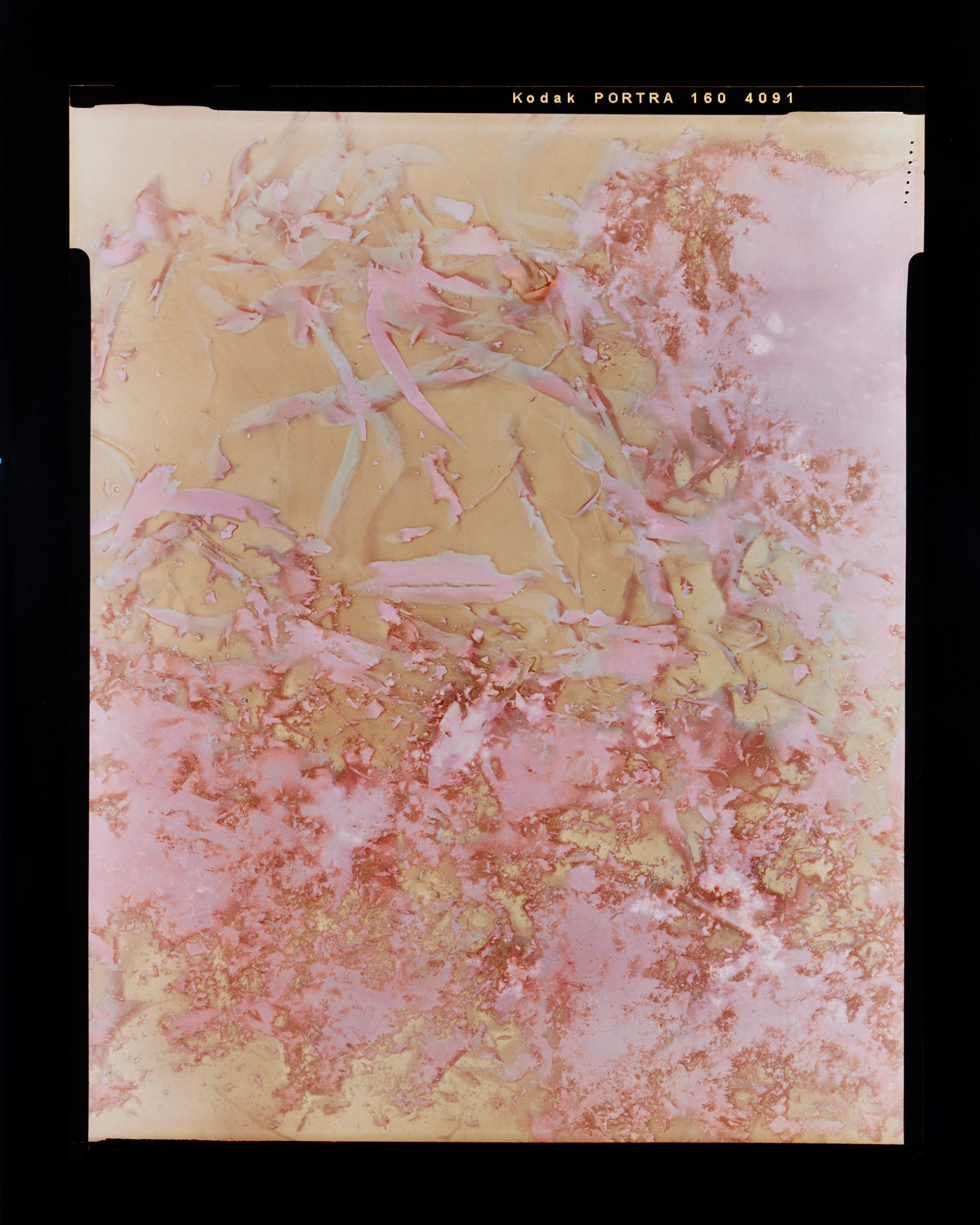

The Last Stand

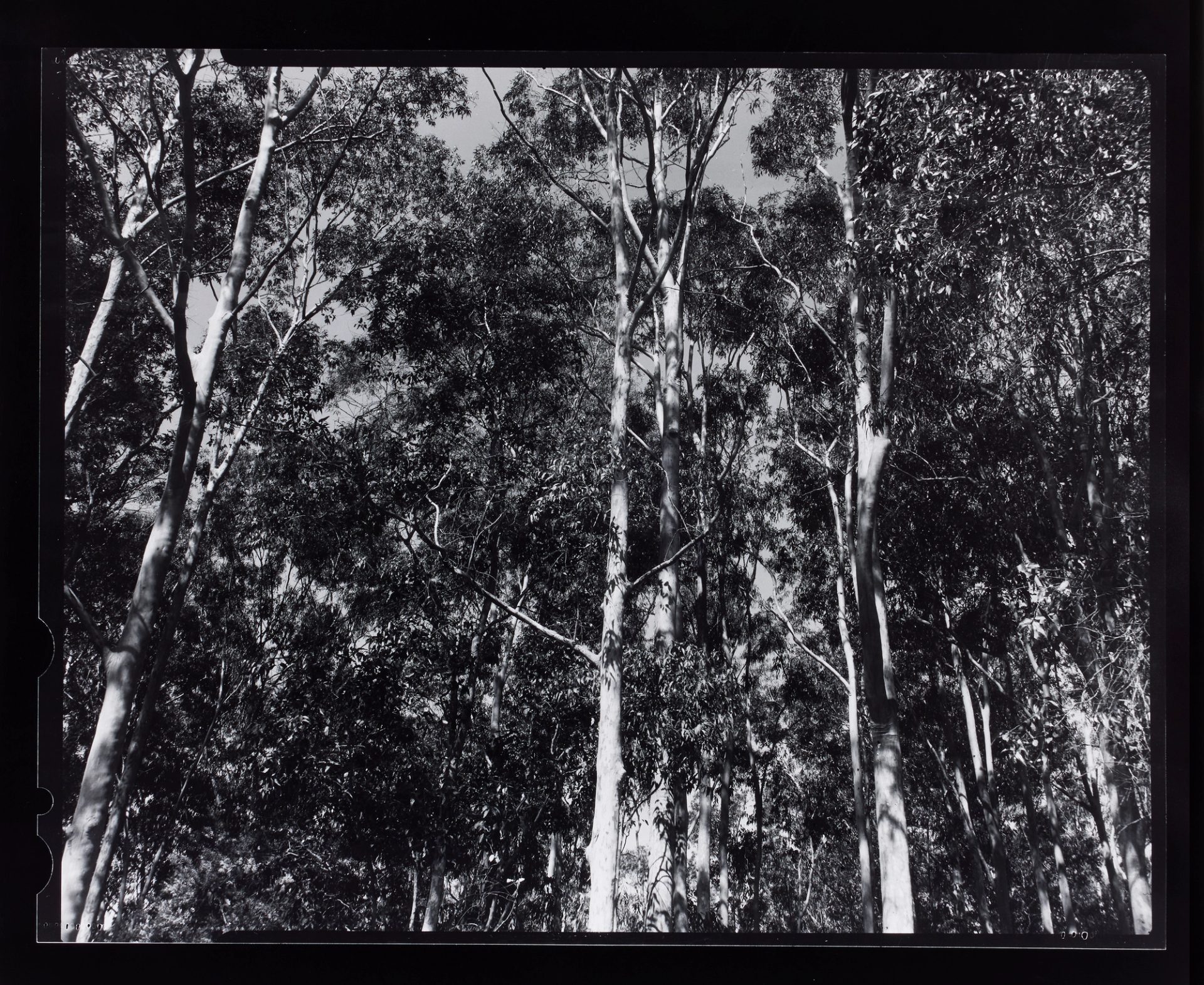

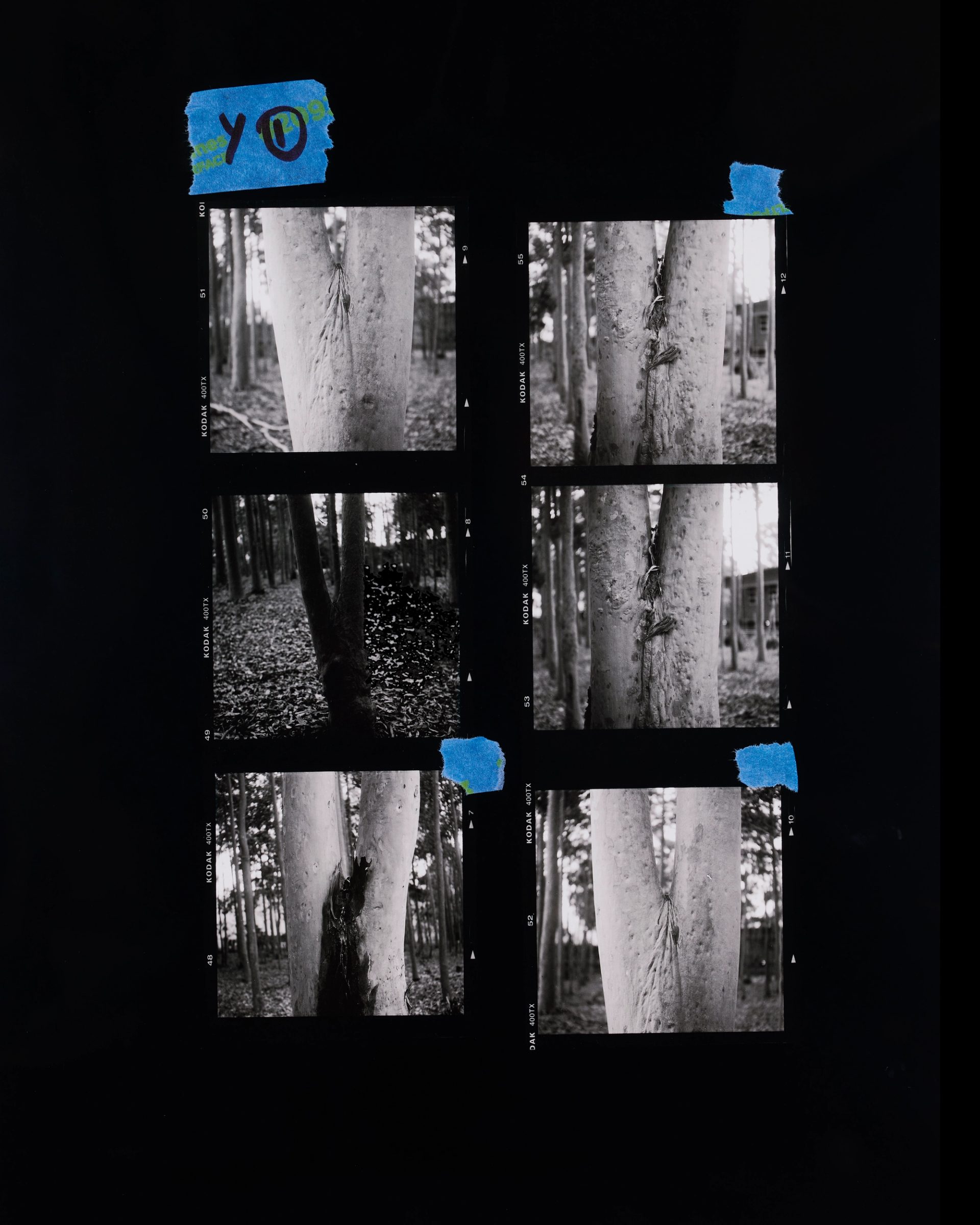

In 2021, Powerhouse commissioned artist Amanda Williams to document the last days of the museum’s former Castle Hill Experimental Research Plantation.

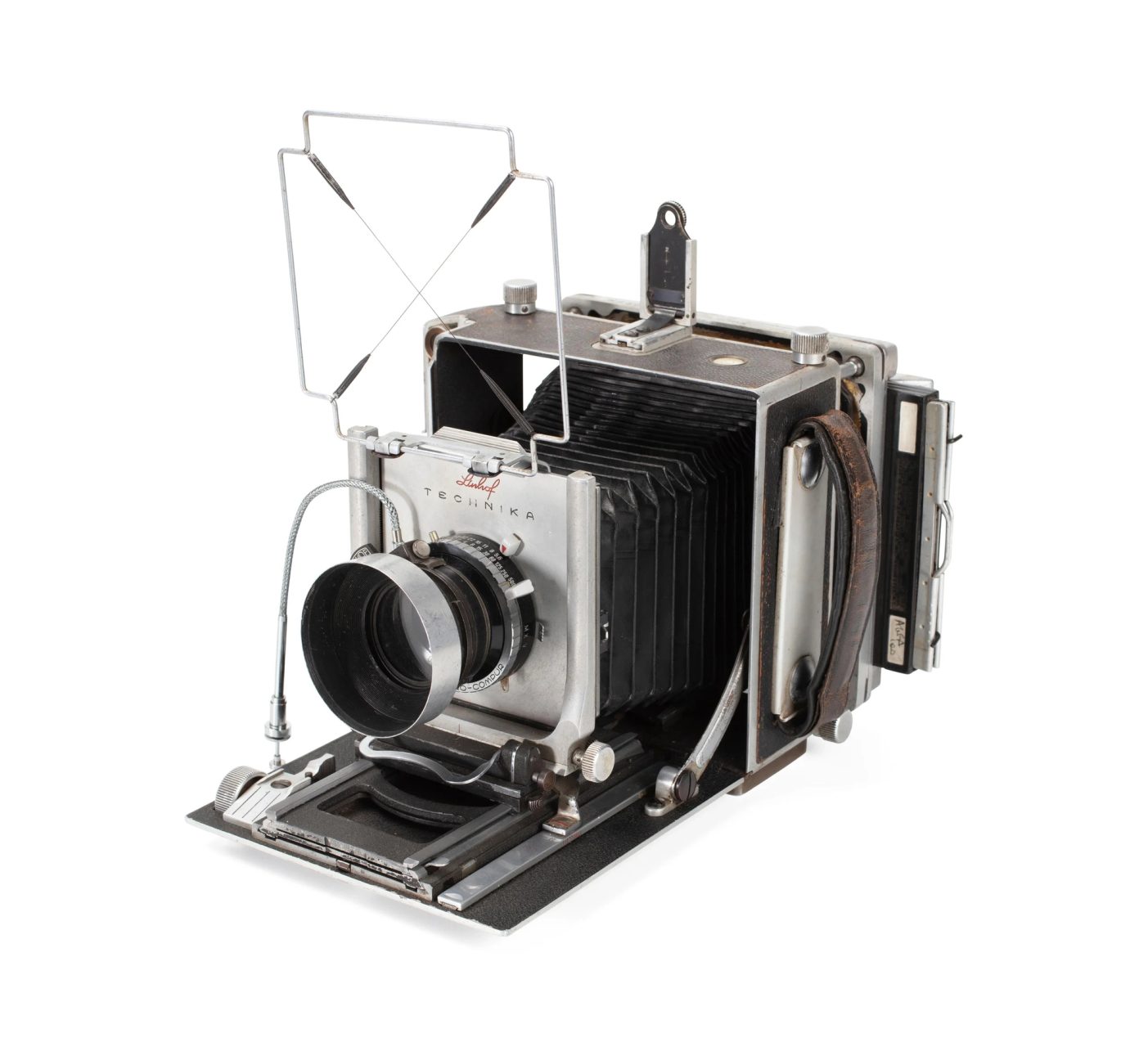

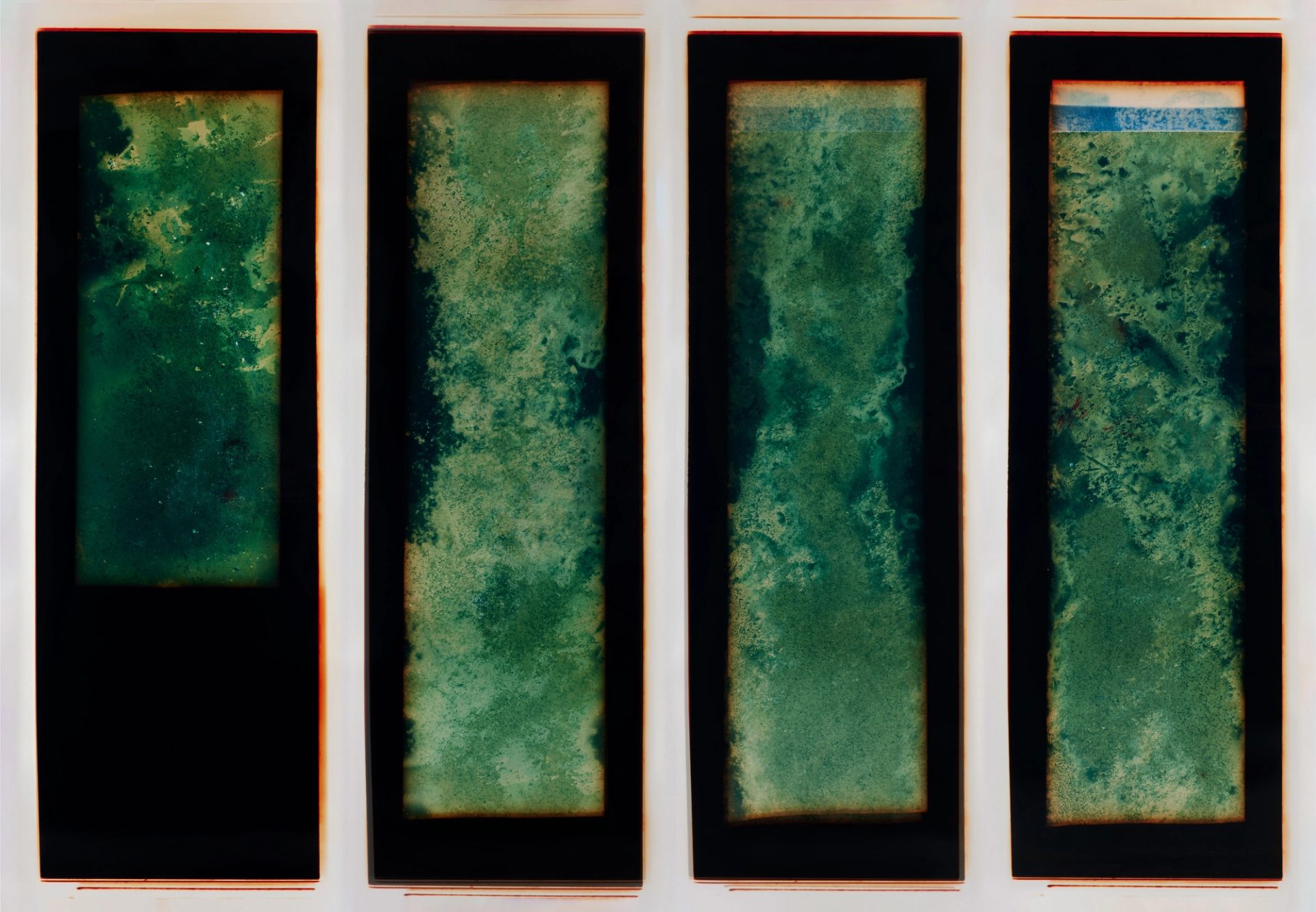

With 327 trees marked for removal ahead of the construction of Building J — a new storehouse for the Powerhouse Collection developed at Powerhouse Castle Hill (part of the Museums Discovery Centre) — the commission was conceived as both an archival recording of the site and heritage interpretation. A significant outcome is a series of artworks collectively titled The Last Stand 2021–23, comprising 32 works that demonstrate Williams’ diverse approaches to image making across eight conceptual engagements with the former plantation site. The Last Stand will be on display at Building J from its opening on 23 March 2024. An earlier selection of 23 works from The Last Stand series featured in the publication Eucalyptusdom (Powerhouse Publishing, 2022). In the culmination of a 3 year engagement at Powerhouse Castle Hill during the $44 million expansion project, Williams trained her sights on the final construction stages capturing the architecture and typology of Building J.