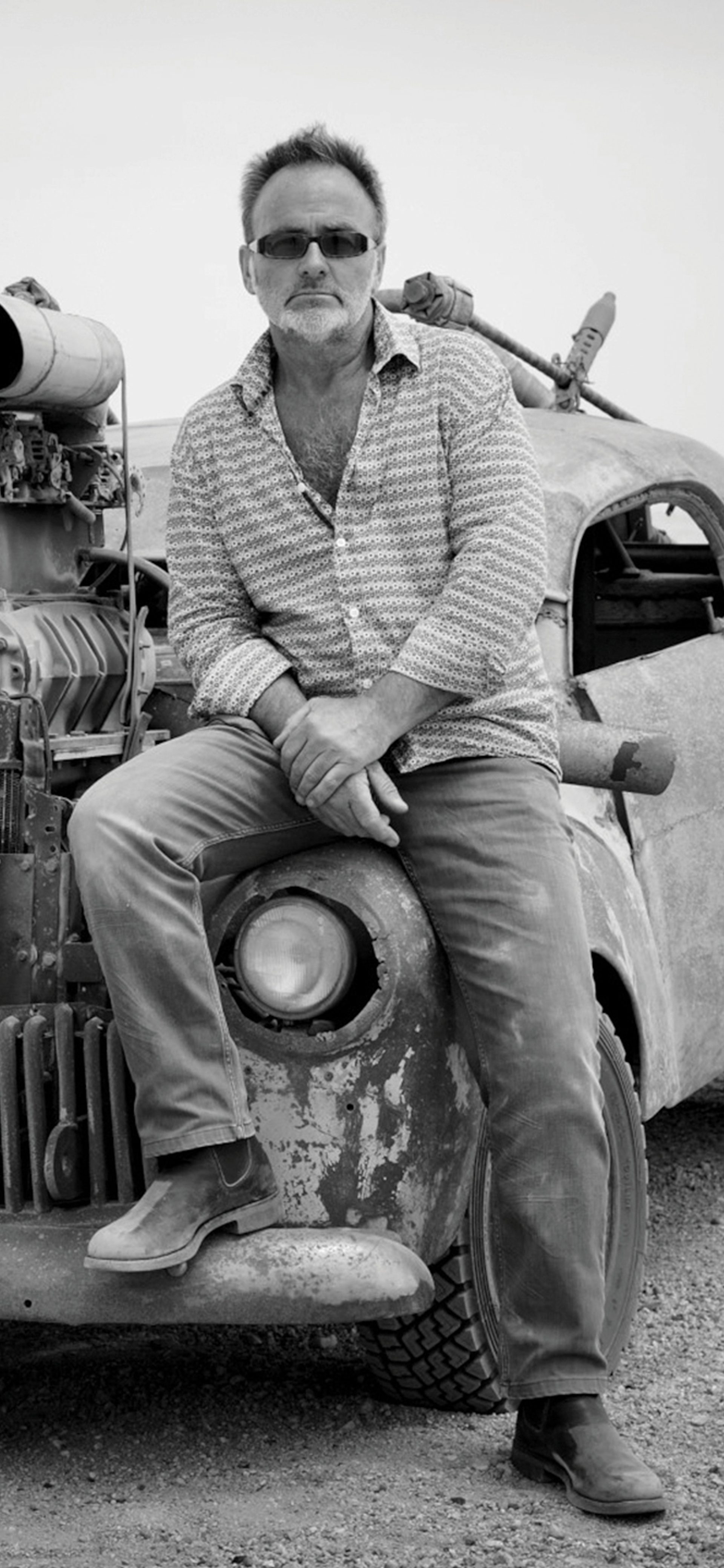

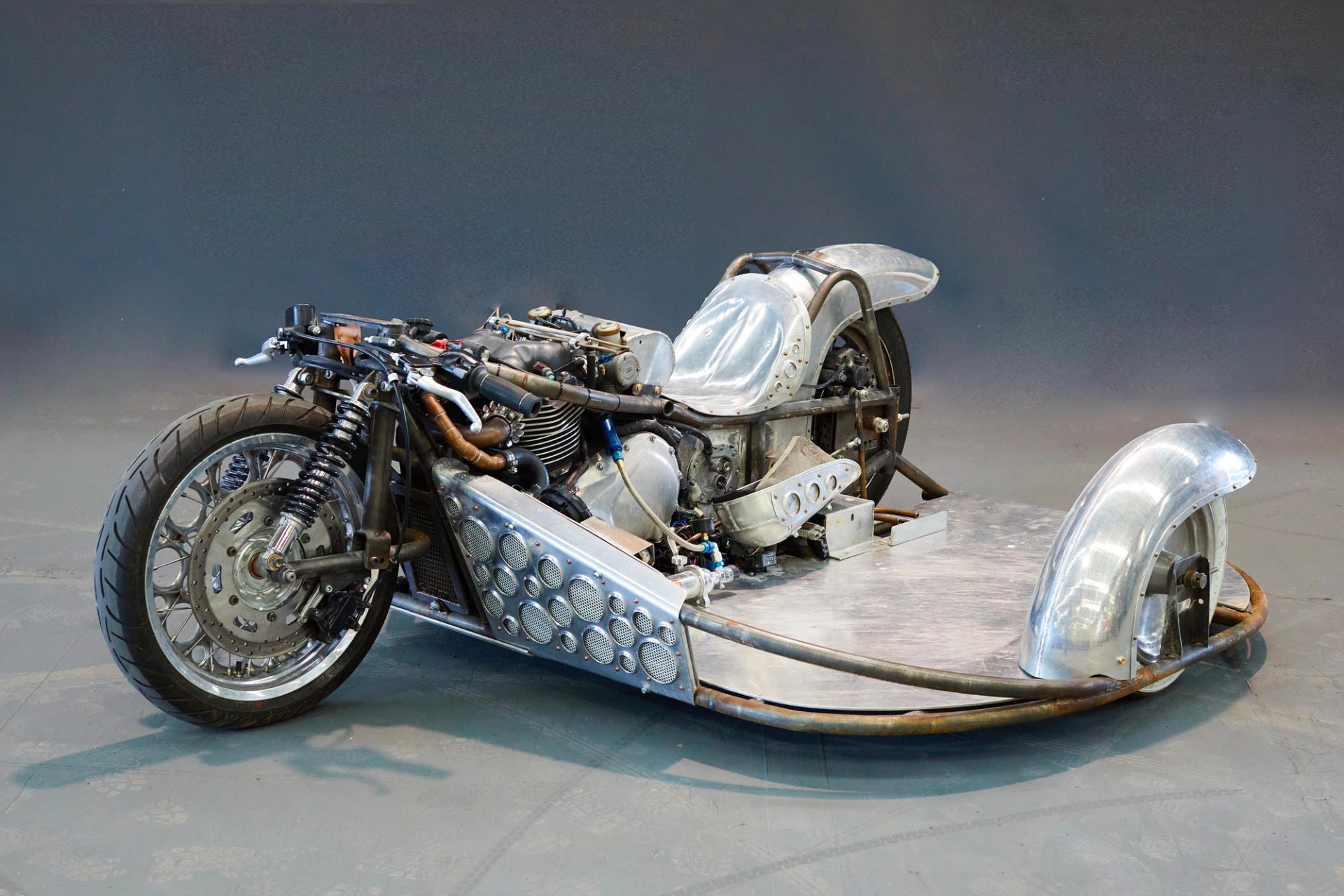

Colin Gibson: Heroism and Peril

In a career spanning more than 30 years, production designer Colin Gibson has shaped the Australian cinematic landscape. From an early gig devising the eponymous bus in The Adventures of Priscilla, Queen of the Desert (1994) to his latest opus – the freaky fleet of dystopian desert vehicles for 2024's Furiosa: A Mad Max Saga – Gibson delights in delivering the unimaginable to suggest the possible. Often working in collaboration with Australian director George Miller – on Babe (1995), Babe 2: Pig in the City (1998) and Mad Max: Fury Road (for which he won the Academy Award for Best Production Design in 2016) – Gibson refers to his method as 'a frantic assembly of odd skills'.

'It didn’t really matter if I was the props guy or designer,' he says. 'I was probably just as loudmouthed and annoying in whatever the named position was'.

In advance of his Future Prototypes talk as part of Sydney Design Week, Stephen Todd pays Gibson a visit to discuss heroism and the perils of CGI.

‘I treat design as DNA – like a double helix. There’s the thread that is the story itself, ostensibly the movie we’re filming. The other helix is all the parameters that feed into it. ’

Stephen Todd Colin, two films you’re widely renowned for are Babe – an animatronic tale of a pig who wants to be a sheepdog – and Mad Max: Fury Road, a dystopic parable of a resource-starved future. Apparently polar opposites, yet one senses a common thread.