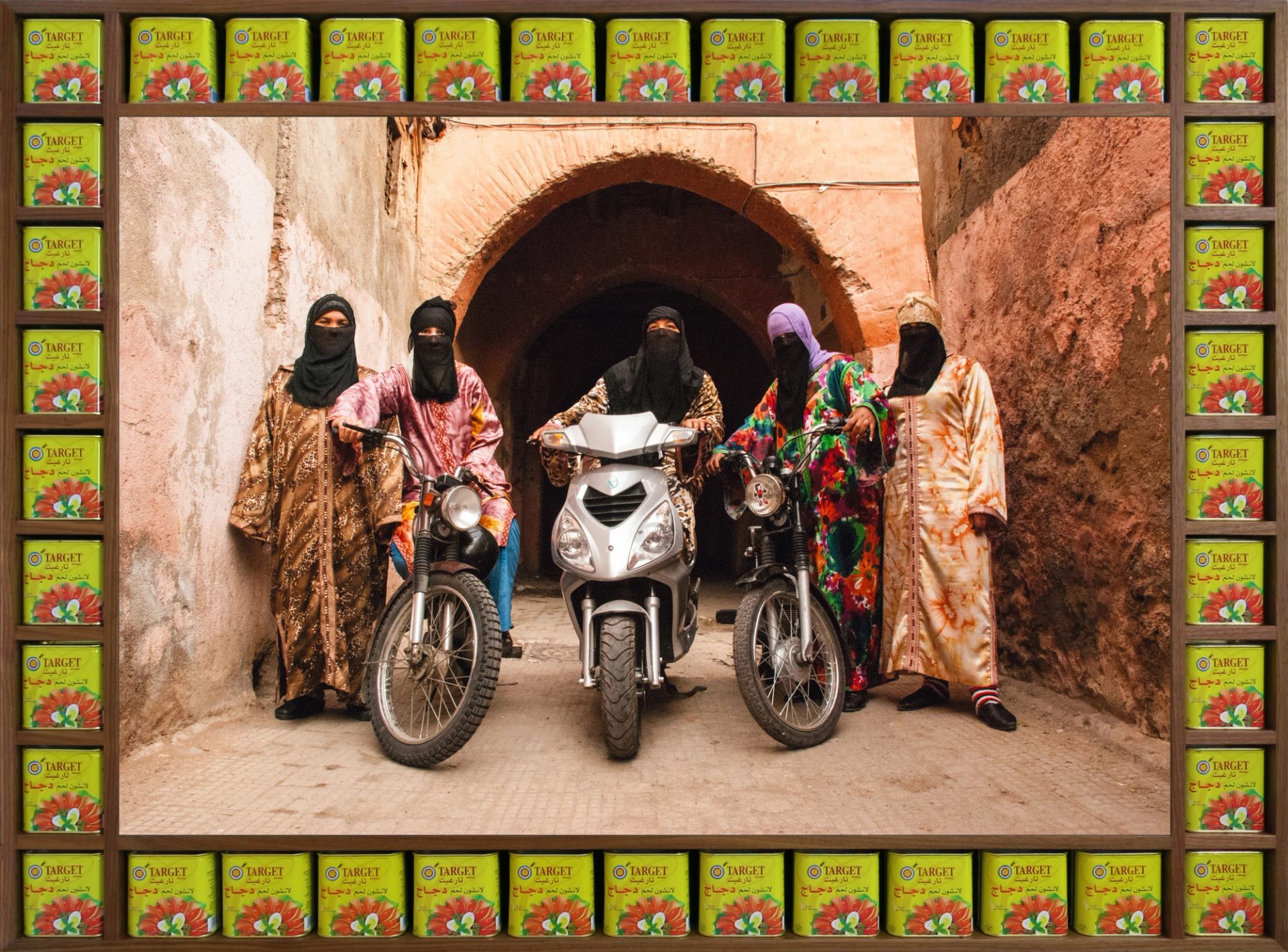

ST Can you elaborate a bit on that idea of ‘highlighting the less clichéd aspect of life in Marrakesh at the same time as leaning into those clichés’?

HH Taking the girls on bikes as an example: people outside of Marrakesh are surprised to see images of veiled women on bikes despite the fact this is the way of commuting for all people in the narrow streets of the Medina. So, while the assumption is often that these are tough women from Marrakesh, they are in fact ordinary mothers, workers and so forth. And then I called some of these early photographs ‘Gang of Marrakesh’ and the series is called Kesh Angels, inspired by the gang Hells Angels and Kesh being short for Marrakesh, which adds another layer again.

ST Are your subjects people you know, or are you doing street casting of passers-by?

HH My images began by focusing on people I grew up with and who inspire me. Then it became friends of friends and friends of friends of friends to the point that, over more than 30 years of practice I have accumulated literally thousands of images of people from many different cultures. I meet people, get an understanding of their country, the traditions, the culture. It keeps me going at the same time as requiring a lot of energy. I'm constantly pushing myself to the limit.

ST How does your styling of your subjects affect what you want to convey of them?

HH The styling part is really a collaboration between the sitter and myself. I try as much as I can to design specific outfits for specific people.The idea is playfulness and that the sitters will have fun, so that’s very present in the design. But I always give options, and when a sitter has got a strong style of their own, I let them wear their own clothes, just adding a few accessories like sunglasses and socks. The idea is that I offer them a platform to have fun, perform and let go of their seriousness if any.

ST What’s the difference between shooting subjects that you choose from your own network and creating commissioned portraiture of the likes of Billie Eilish or Cardi B?

HH Of course, it’s different in that you’re being paid to create images of global celebrities for commercial purposes. But actually, they’re coming into my world because they admire something or things about that world. So, I just look at them as human beings and welcome them in.

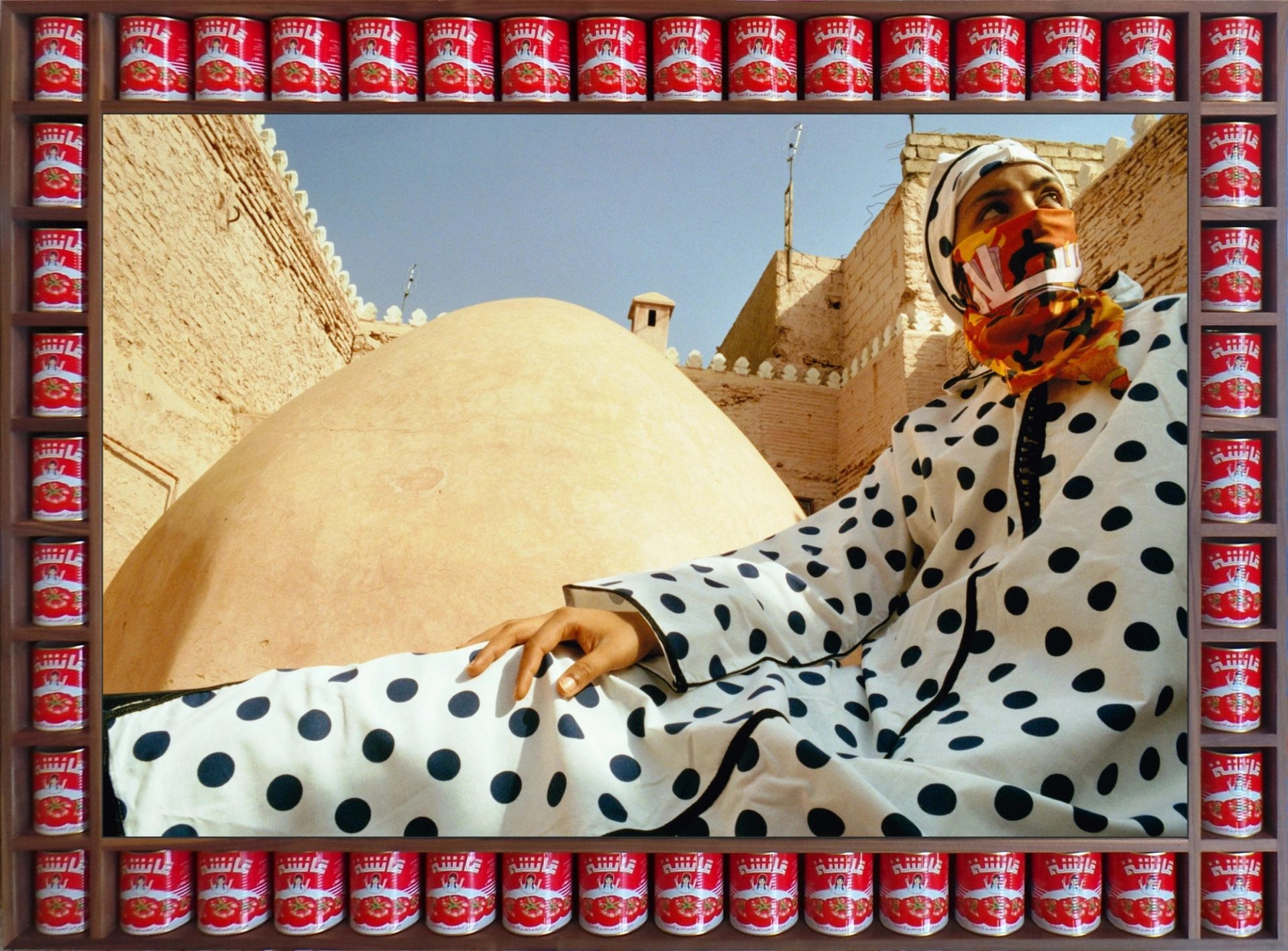

ST The idea of ‘framing’ is important to your approach. The way you set up an impromptu studio by marking out space with vibrant fabric, for instance. But also the way you literally frame your images with canned food and other everyday consumer goods.

HH In a way, it’s about creating a link to traditional Arabic art with its very repeated non-figurative motifs but updating that with a contemporary edge. It was also about countering a kind of snobbism in the contemporary art world back when I started that didn’t consider photography quite up to par. I recalled going into museums and looking at oil paintings from the 1600s and 1700s which were all in these over-the-top gold frames. I remember thinking, the particular frame is built for the particular painting and will stay with it no matter how many times it changes hands. I thought to ironically ‘elevate’ my images by constructing frames from everyday grocery items – which have a highly decorative aspect, especially when assembled in repeating series.

I found along the way it had an unintended effect – originally, anyway: it’s been great because it breaks all barriers. People see Coca-Cola or Louis Vuitton or other well-known brands and are not just drawn in but given a level of comfort through recognition. Thinking about it, I believe that’s an underlying current running through all my work. I’m from council flats in London. I came out of school aged 15 with zero qualifications. So, museums, galleries, ‘culture’ were never in my comfort zone. Now, after 30 years, it’s great that I can have my friends hanging with me in the museum and people getting high on it.