JG Could you describe the milieu in which you made du Fermier?

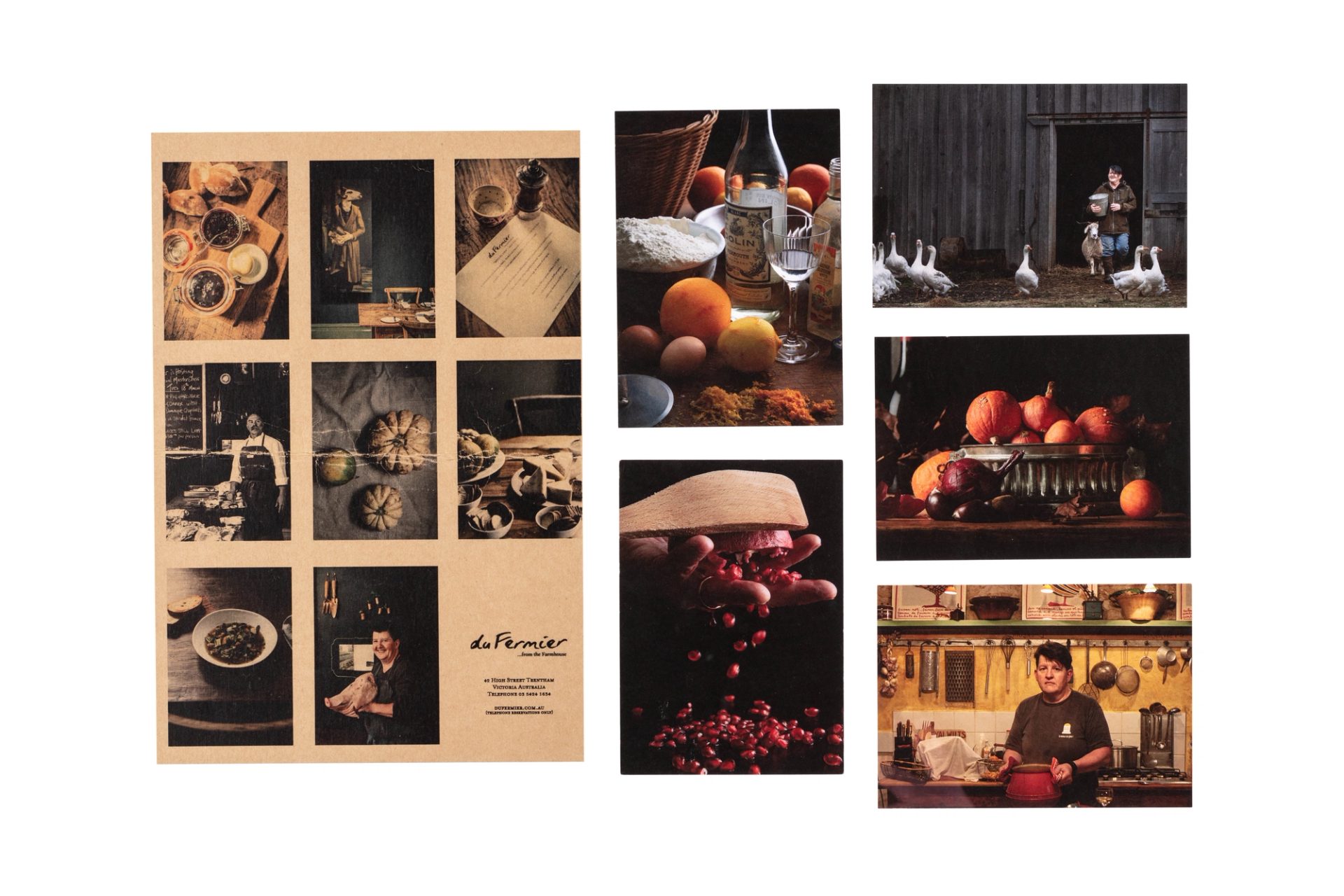

AS After selling Bistrot I opened du Fermier in Trentham, a tiny weatherboard country town with only one proper brick building. The garden became so centric in my cooking that I don’t think I could construct a three-course menu out of the ether anymore. I would go out, see what was ready, and shuffle the protein of the main course and then work either side. I fell in love with Susan, my now wife, and we bought Babbington Park, a 23-acre (9.3-hectare) property of incredible beauty in Lyonville, 10 minutes out of Trentham on the way to Daylesford. With rich, volcanic soils, it had been an organic farm, so it doesn’t have any of the nasty poisons. We moved here in 2017, which meant that I had to start the garden all over again.

JG Can you describe the current menagerie?

AS There’s a Westie and a cairn. There’s the four cats. There’s the nine cashmere goats, for me to shear. There are eight miniature Cheviot sheep, too many cows. Susan’s read the riot act and some of them are going, but at the moment there are six miniature Galloways. There’s a lot of Sebastopol geese and two Toulouse geese. There’s five black call ducks. There’s Mr Ping and Martha and the Love Child, but they’re mixed breed. And then there’s the French Marans known as the hungry girls. There’s the blue Orpingtons known as the fluffy bums. There’s the speckled Belgian, Bearded Belgian d’Uccles known as the cosmonauts because they look like the cosmos on their feathers. And there’s the Chala Cartel, which is the Colombian one. There’s the cream legbars and there’s some old Araucanas. There’s all the rogues who are CSIRO white leghorn bantams. And then there’s the Crèvecoeurs, the endangered chicken from Normandy.

JG A lot of those are pets, aren’t they?

AS They’re all pets, but they have a purpose. The three ruminants keep the grass down. They are breeds that need a little care in the world to keep their gene pools alive. The goats and the sheep are stabled at night. All of that is part of our circular life where all of that bedding creates the compost that creates the vegetables. The Americans would call it farmsteading. I suppose the Scots would call it crofting. It’s very much that small-scale farming where everything leads into each other, and that’s how we grow the food.

JG Annie, you’ve been very vocal about mental health.

AS I’ve struggled with mental health all my life. A commercial kitchen was a place where the door was closed and people behaved in a way that is now no longer acceptable. It was a very adrenaline-fuelled, performance based, high-octane environment of pressure, and gas and knives and heat, and fury and joy and creativity. You worked incredibly long hours. And you spiralled. There were cultures of alcohol, of drugs. The model was that you worked as hard as you possibly could and you would get somewhere. The very first time I’d seen a psychiatrist, she said to me, “This is not a healthy work balance.” I said, “But that’s what we do.” And she said, “Well, you need to understand that your work is not everything.”

I went through a phase living this bucolic life of having a successful restaurant, a kitchen garden. I was about to become a cookbook author. I was my own little legend in my own little lunch box. It was so hard keeping up appearances and I just didn’t want to wake up anymore. I felt great joy in what I did but that space between being Annie Smithers and just being Annie was a very dark and sad little place.

You either make a decision of doing something to change it, or there is the other option, and we know that is a terrible curse in our industry. So I did seek help. And the tools, the reality of having that level of professional care, is one of the reasons that I will happily talk about it to anybody, because it helps to normalise it. It taught me there are three contributors to my sense of depression and anxiety. In those early years I was definitely agoraphobic. The only way that I could get out the door was to put on the Annie Smithers persona. Thankfully I’m well over that now and I’ll trot out anywhere. Lack of sleep is the foremost trigger for me. Financial stress is another, and overwork.

In this microcosm of Annie’s restaurant world I’m never going to be overly rich, but I live a nicely constructed life. That has come to pass by placing limits on what I can do, what I expect others to do, coupled with restricting supply. When I stopped chasing the dollar and expecting to earn more and more money, life became a great deal easier and more financially viable.

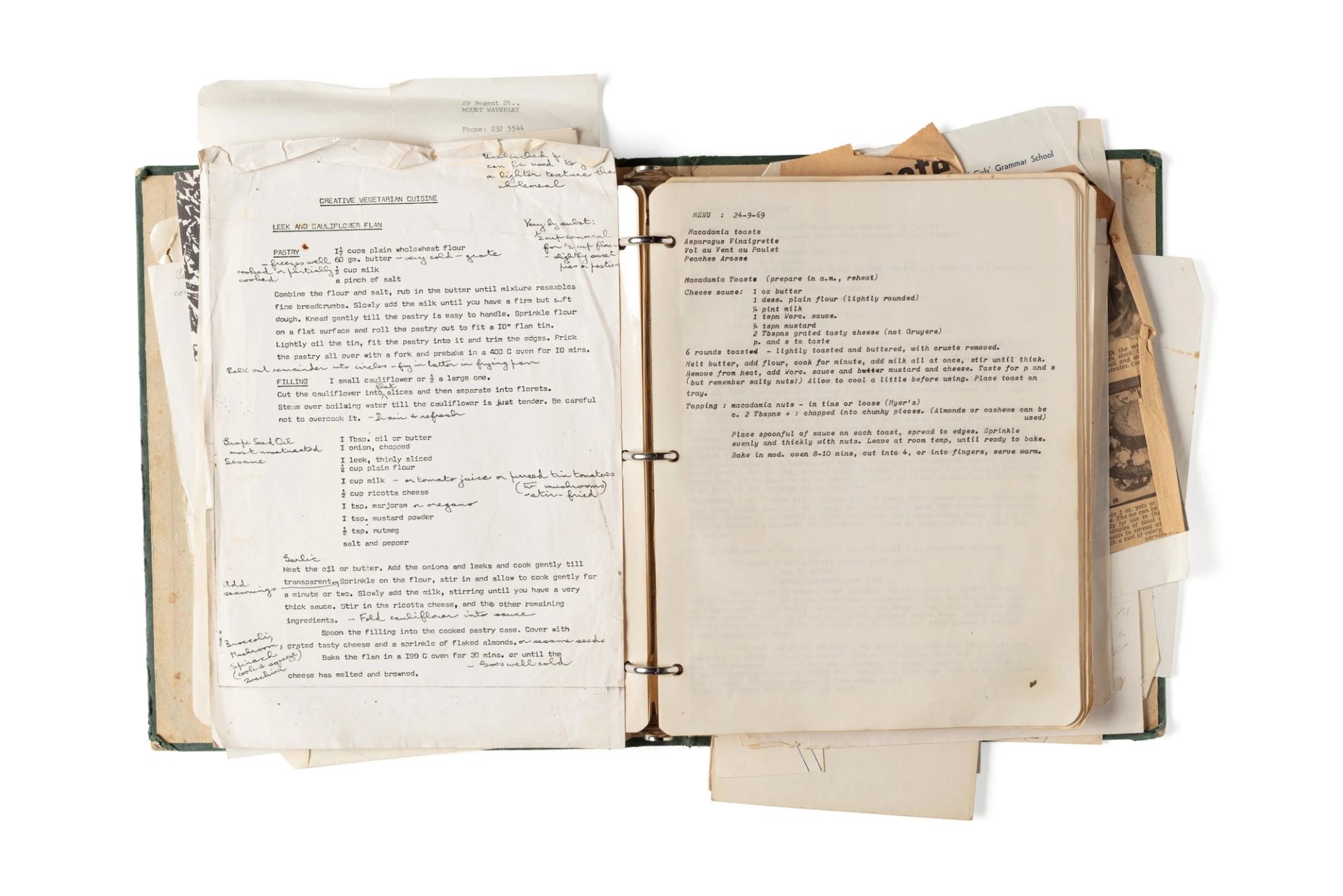

I get in there, I put on the bread, and that Zen moment arrives of the hands know what to do, the head knows what to do, and I follow my heart and just cook.