JG Can you recall who some of the chefs were that you worked with in that way early on?

EC Well, Rick Stein sought me out from the work that I had done. I have a huge respect and admiration for Neil Perry’s knowledge of produce and process. He’s been very supportive of me.

David Thompson… I can remember going to Darley Street Thai and being wowed by the food that was there. A lot of fun on the journey working with him.

Stephanie Alexander, who had a huge reputation and I admired and respected what she’d done. I tried hard to complement that with imagery.

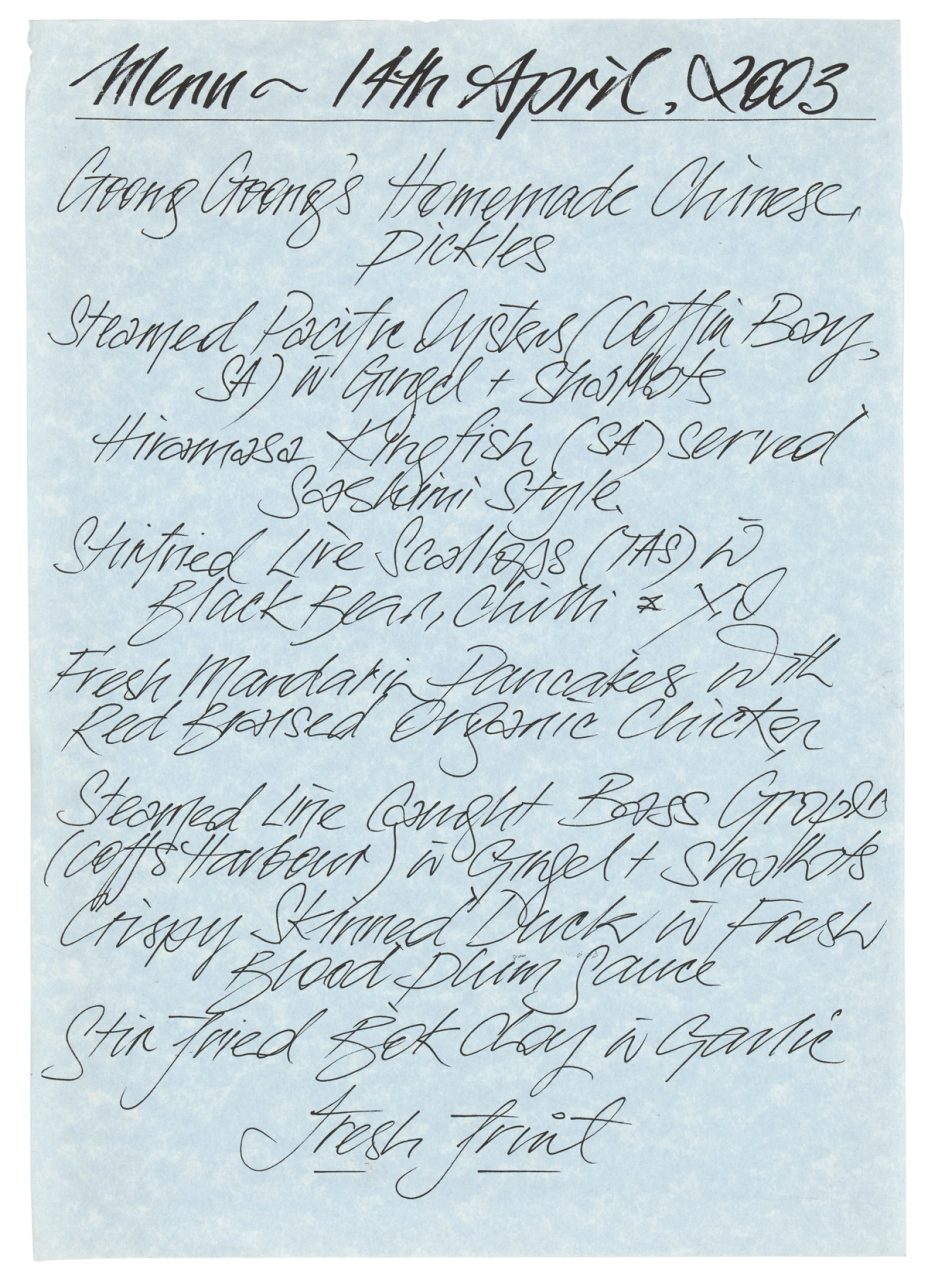

Kylie Kwong is another really passionate chef and her personality comes out in her food. I would never approach shooting a Kylie Kwong dish like I would shoot a Neil Perry dish. Kylie’s process is quite captivating. It’s important to capture the personality of a chef. It’s the way that they plate and combine tastes and textures. It’s the way that they are so passionate about produce. It’s important not to disregard that and put your own style on top. Karen Martini is a classic example.

Maggie Beer is a passionate and heartfelt chef. You can’t help but be engrossed in that atmosphere and it’s very homely, quite approachable, quite simple. Whereas somebody like Andrew McConnell is quite a leader in the culinary world and his audience are sophisticated restaurant-goers. I try to photograph the food and create the imagery that has more of a graphic interest so that it’ll lead the viewers to analyse why things are placed in a certain way, most likely Japanese influenced or Asian influenced.

JG Let’s come to your work for The Saturday Paper and the style of photography that you bring to that commission and then how you had to pivot in Covid.

EC I took on the project trying to represent food in a slightly different way, to show there can be a lot of interest and romance in the process of cooking rather than the finished product. That may just be a potato completely covered in dirt. I feel like that is a piece of art on its own.

I’ve set a template where it is actually a mini story, and it goes from produce, through process, to final dish. It’s important to show some of the key processing elements and what it looks like at a particular point in time.

In Andrew’s kitchen in one of his restaurants, or Karen’s kitchen at home, there’s always a plethora of stuff going on behind, whether it’s shopping bags full of carrots, or Annie Smithers and her baskets full of turnips that she’s just dug out of the ground. They’re such beautiful, captivating things that they’re an important part of the story.

That all changed during Covid. Because of the lockdown, nobody was allowed to travel anywhere, as we all know. Fortunately, digital technology has advanced enough that we could shoot them live on the iPhone.

I’m talking to David Moyle, who’s in Byron Bay. He tells me what his intentions are, what he’s preparing for the dish, and then we start to hash out together what that storyline could look like. That involves Dave walking around his house or the kitchen he’s in, finding surfaces from the most unexpected places, but I’m actually not in the same room, or even in the same state, or in some instances not even in the same country.

Together we work out how we would shoot that and fulfil the template. I have to talk the chefs into thinking a little bit left field. Their iPhone is literally pointing at the tabletop, and I’ll ask them to move this bowl to the left. Do you have a large spoon that we could put in there? Maybe the garlic looks better if it’s chopped, O Tama? She runs off and chops it and puts it back.

Then, they send it down the line where I will look at it live and give more feedback and look at using digital enhancements to correct the images. We increase contrast, alter colours, change lighting. It’s actually using my film skills from all those years ago and applying that digitally onto the images they’ve supplied. It’s a different way of working. My peripheral vision is now channelled only through their iPhone. I find it challenging but we are working around it.

JG Where would you say Australian food has come to now?

EC We’re very fortunate, even though some people might not think so, that we’ve had huge influences from all around the world. Somehow we have, excuse the pun, ended up in a melting pot. I feel it’s uniquely Australian because it is a massive mix of cultures. Back that up with the produce as well. I think we’re very fortunate in this country to have the quality.

More and more, and particularly through chefs like Neil Perry and Andrew McConnell, there is this increasing interest in provenance and methodology, and creating produce that’s well sustained, environmentally friendly and incredibly tasteful.