Henri Mallard: Bridging Worlds

More than a century since his camera captured the construction of the Sydney Harbour Bridge, Henri Mallard’s iconic photographs have entered the Powerhouse Collection, strikingly spanning the applied arts and sciences.

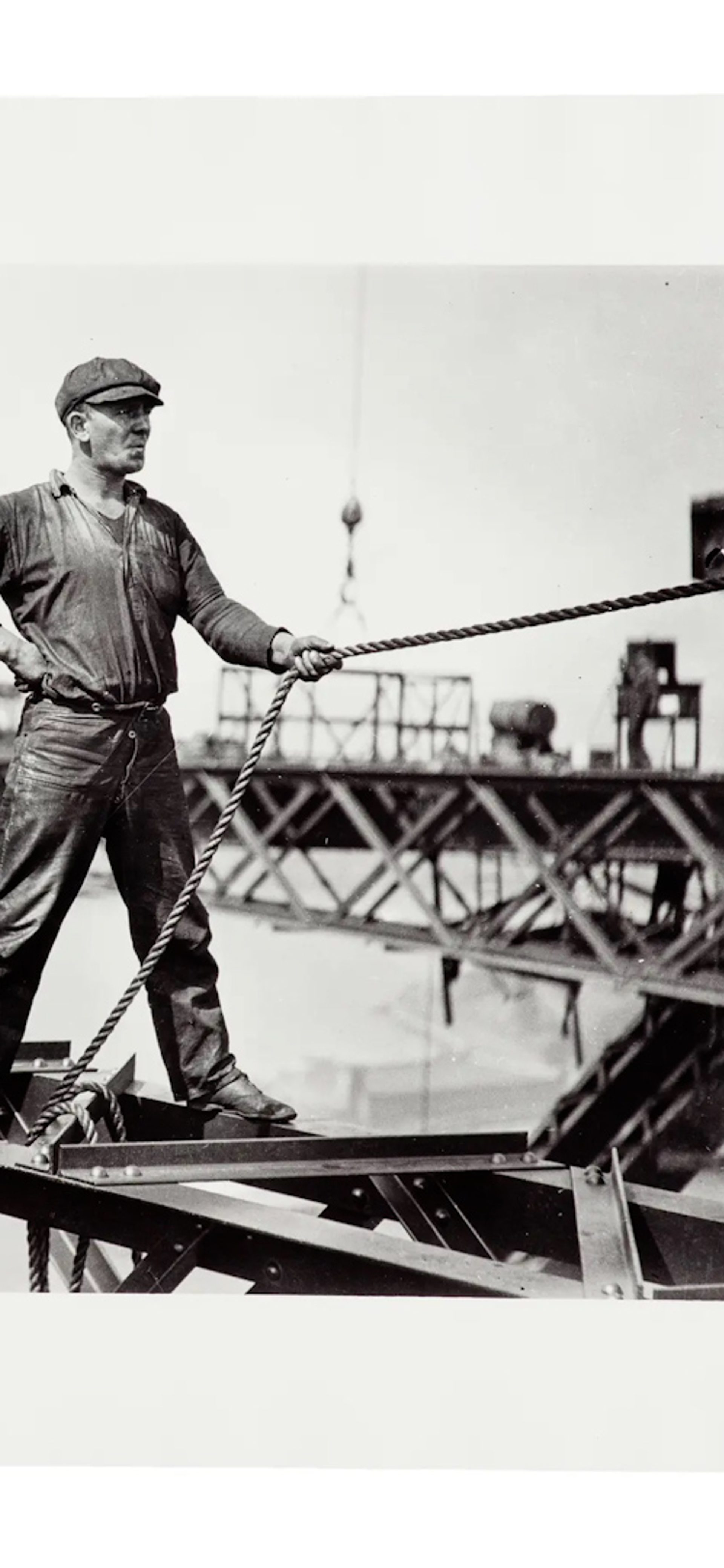

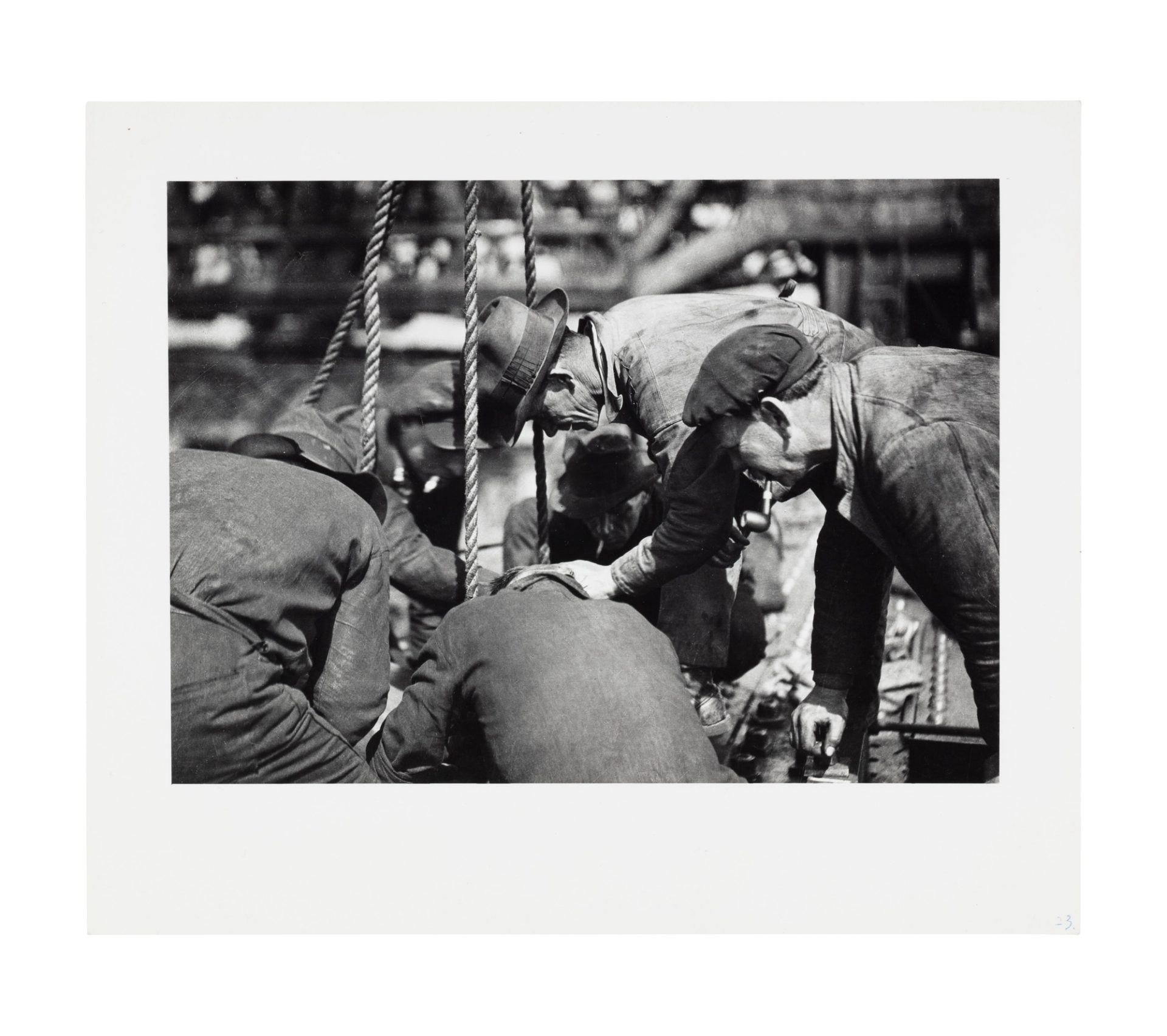

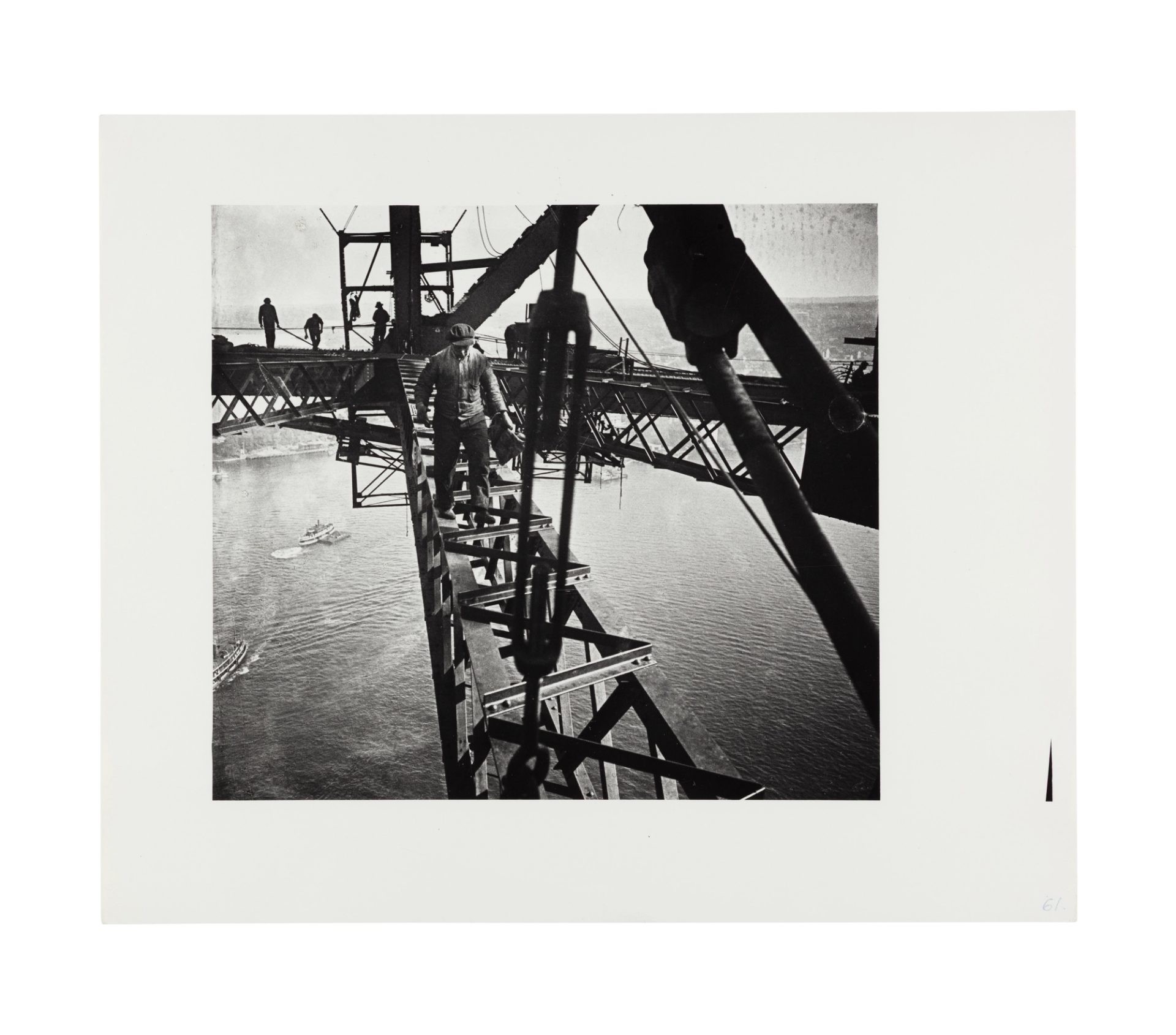

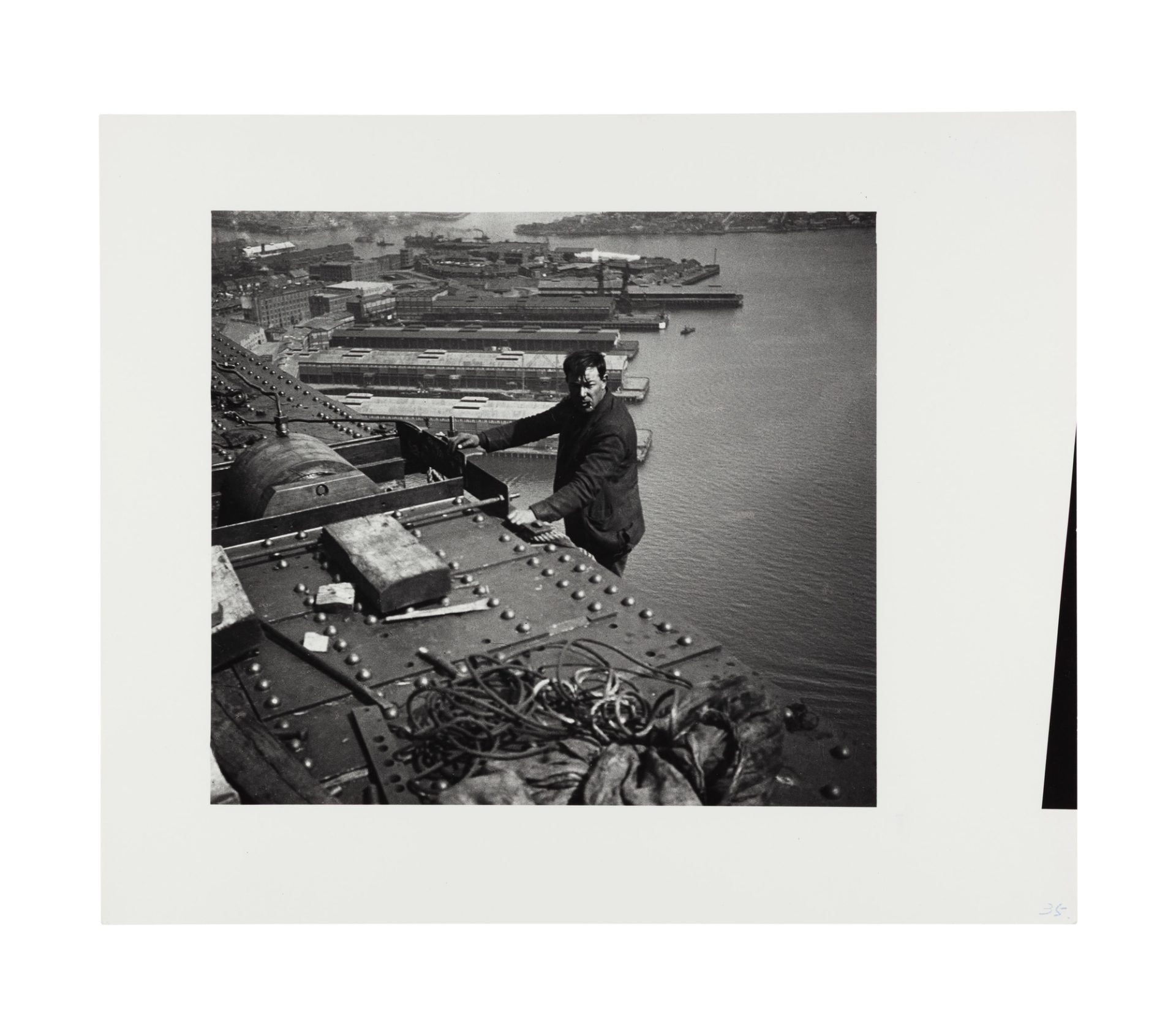

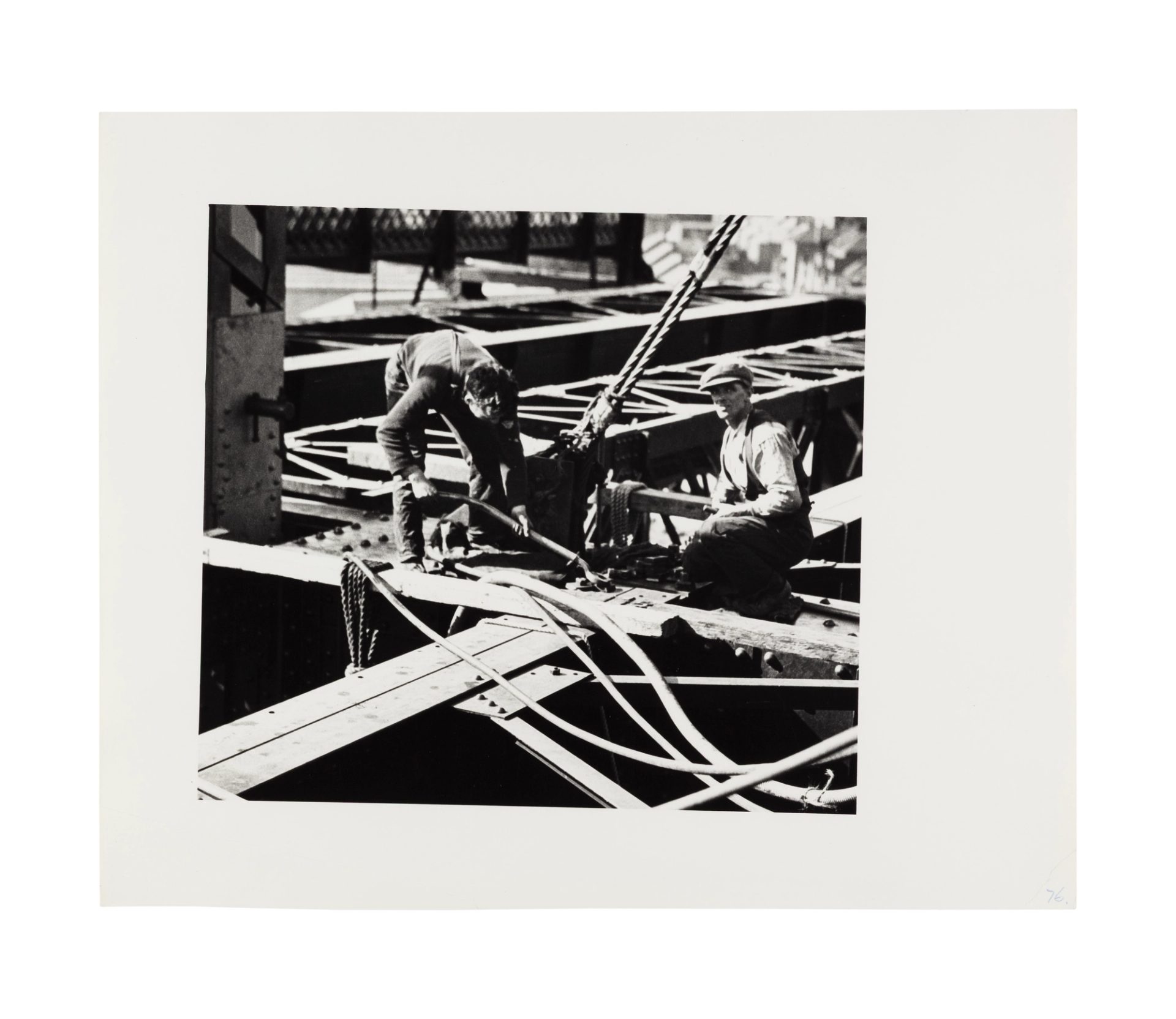

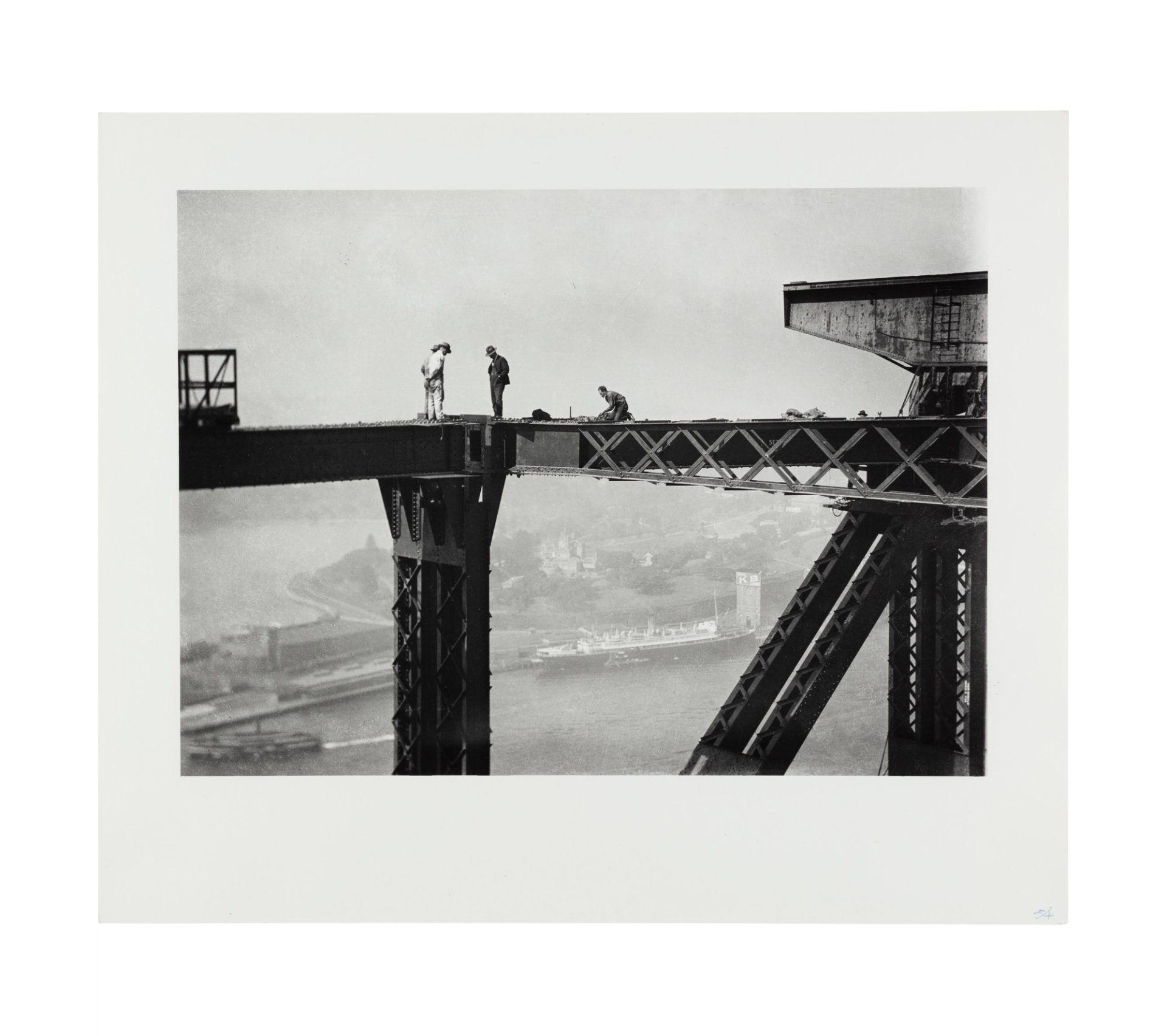

‘He is in amongst it with the workers, on ground level and aloft, on the deck or the girder, and dangling.’

After Henri Mallard died in 1967, even his family was astonished by what was found in his shed. Mallard’s dentist son Paul knew his father had managed Harrington’s, the Sydney supplier of photographic goods where he had worked for 52 years, and that he’d been a passionate photographer and filmmaker before World War II, but nothing quite prepared Paul for the discovery of dozens of glass plate negatives gathering dust in the shed.

‘Paul was very surprised,’ Lisa Moore says of their longtime family dentist who retired in 1989. So surprised, in fact, that Paul called on Lisa’s father, the photographer David Moore (1927–2003), to inspect and identify the images captured in the decades-old glass. ‘Dad was overjoyed to find what he found there,’ she recalls, ‘and realised the significance of them as a collection.’

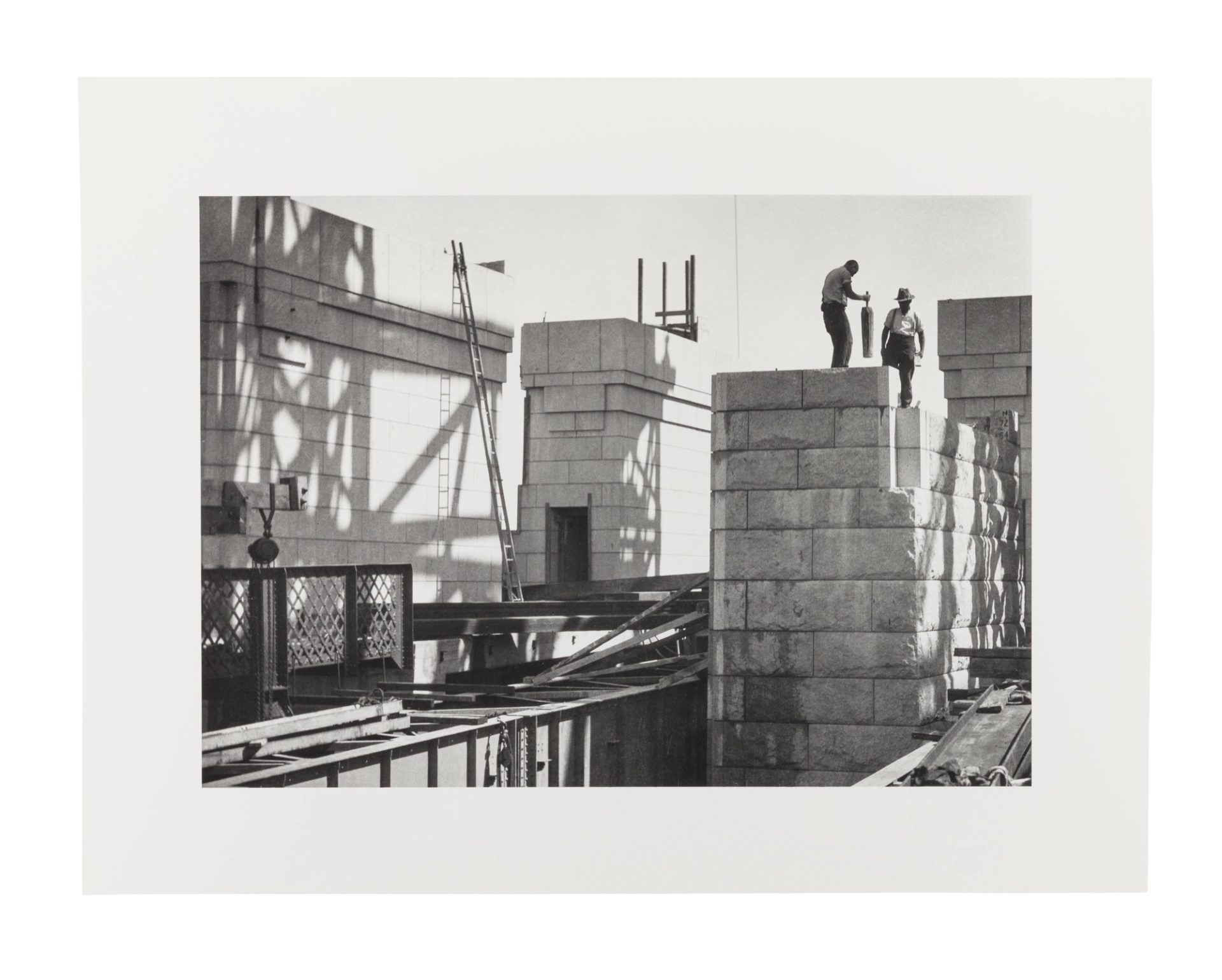

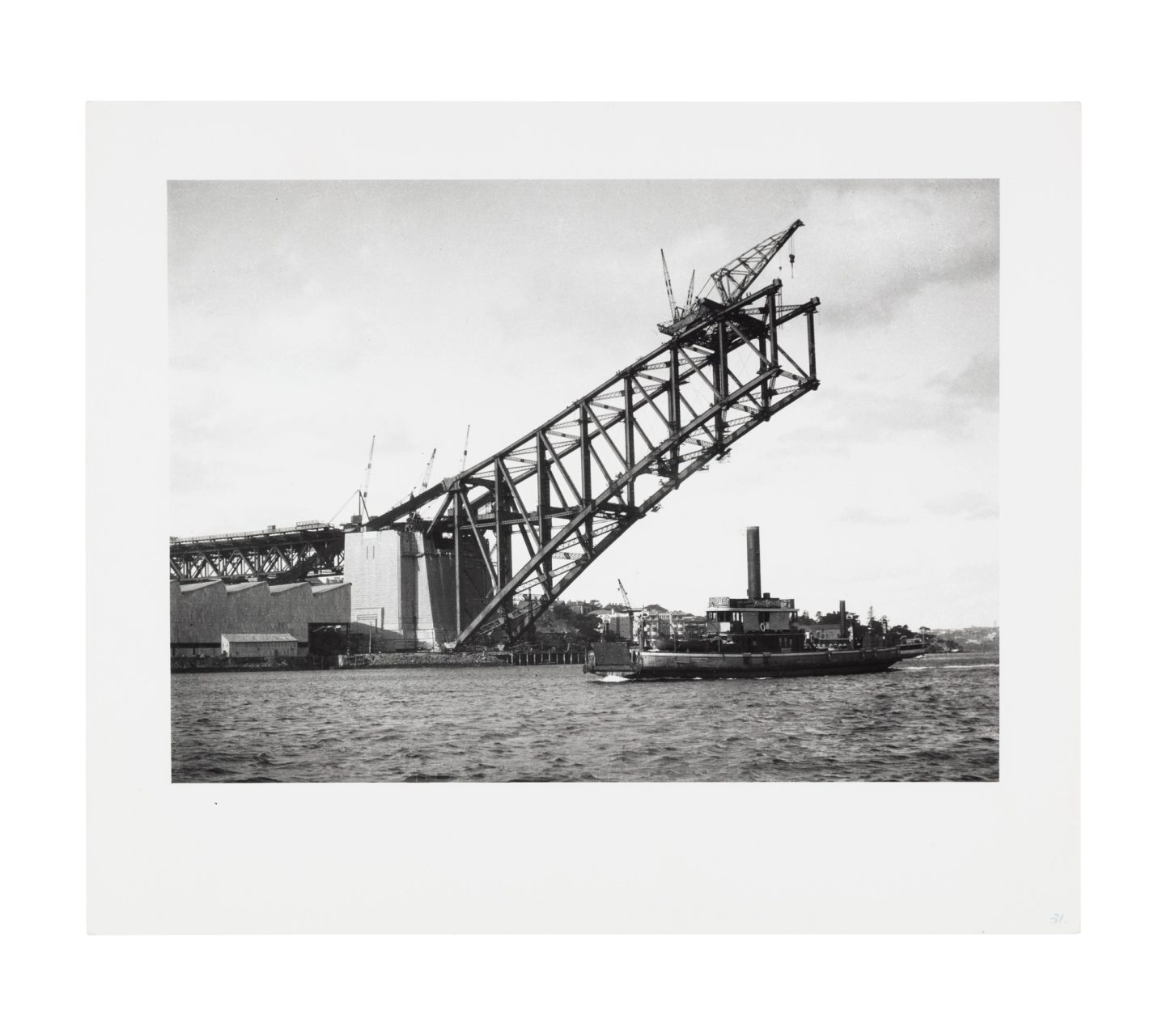

There were black-and-white images of men in slouch hats and dungarees – labourers, riveters and dogmen – their faces creased and squinting at the sun; other images followed the journey of barges laden with metal as they laboured across the chop of Circular Quay. However, most images captured the bridge the men were constructing: the cobwebbed curve of latticed steel that arced 503 metres across Sydney Harbour. The name of the photographer, like many of the men in the pictures, had been eclipsed by the icon that was being erected from steel and granite and which, on completion in 1932, spanned the city’s diverse society and geography. But David Moore immediately recognised the importance of Henri Mallard’s images.