Power of Place: Merilyn Fairskye’s Yesterday New Future (Liddell)

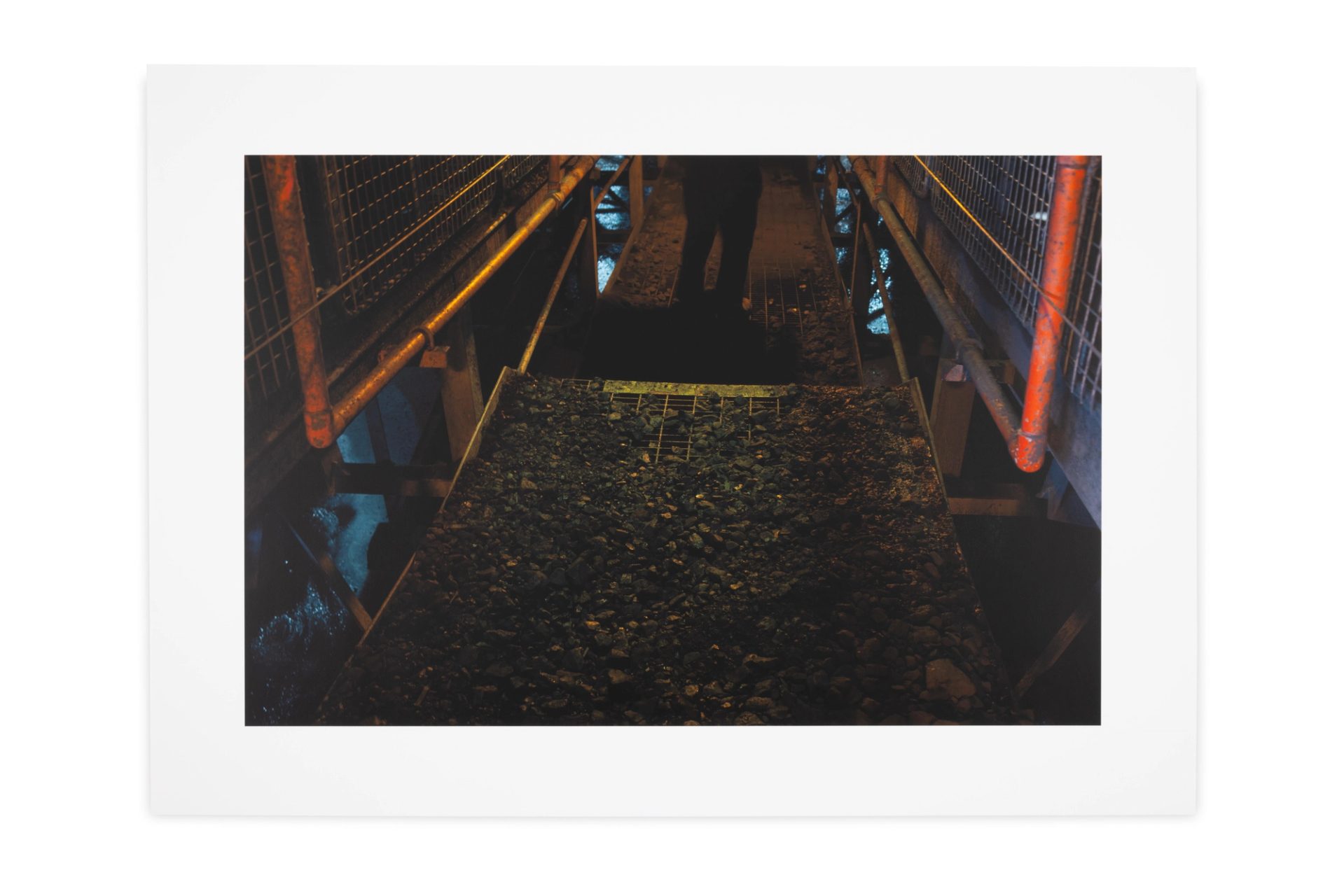

Powerhouse photographic commission Yesterday New Future (Liddell) by Merilyn Fairskye captures Australia’s oldest coal-fired power station on the cusp of generational change.

‘My big interest has been in looking out at the world and what’s going on, rather than plumbing my own personal stories. There’s so much there that is so utterly engaging in terms of contradictions and paradoxes that are really interesting things to tackle.’

Commissioned by Powerhouse to document the last days of the Liddell Power Station in early 2023, artist Merilyn Fairskye felt herself travelling TARDIS-like through time and space. Not only was her commission to encompass Liddell’s half-century as Australia’s oldest coal-fired power station, but as an artist who has long explored the nexus between place, people and power, Fairskye felt compelled to reckon with the Hunter Valley site’s many thousands of years of history as an important hunting and gathering place for the Wonnarua Nation. ‘It was a seriously interesting project,’ she says, ‘and one where I felt I had no idea how it would unfold.’

With a methodology honed since the early 2000s for documenting challenging industry-forged environments – from Pine Gap to Chernobyl and Maralinga – and for interrogating place through a combination of lens-based media and social history, Fairskye felt primed for any outcome. Yet for her first day at Liddell in February 2023, she was unexpectedly transported back 50 years to her days as a painting student in the early 1970s. Then living in a share house in Sydney’s Ultimo, she had stumbled across a vermiculite factory down the road which she photographed at night with her Minolta SRT-101 camera. Walking into Liddell half a century later, ‘I felt an overwhelming sense of familiarity with this dirty, smelly, noisy place that took me right back to the vermiculite factory,’ Fairskye recalls. ‘It’s something about when the story of a place is simply embedded in its walls and in its floors and in the sounds that you hear.’