Mutual Obligation

From heartbeats to brainwaves, economic cycles to cosmic orbits, oscillations can be found everywhere. This podcast takes artists and listeners deep into the Powerhouse Collection of half a million objects to unearth stories about the vibrations, fluctuations, and movements woven through our world – and beyond it.

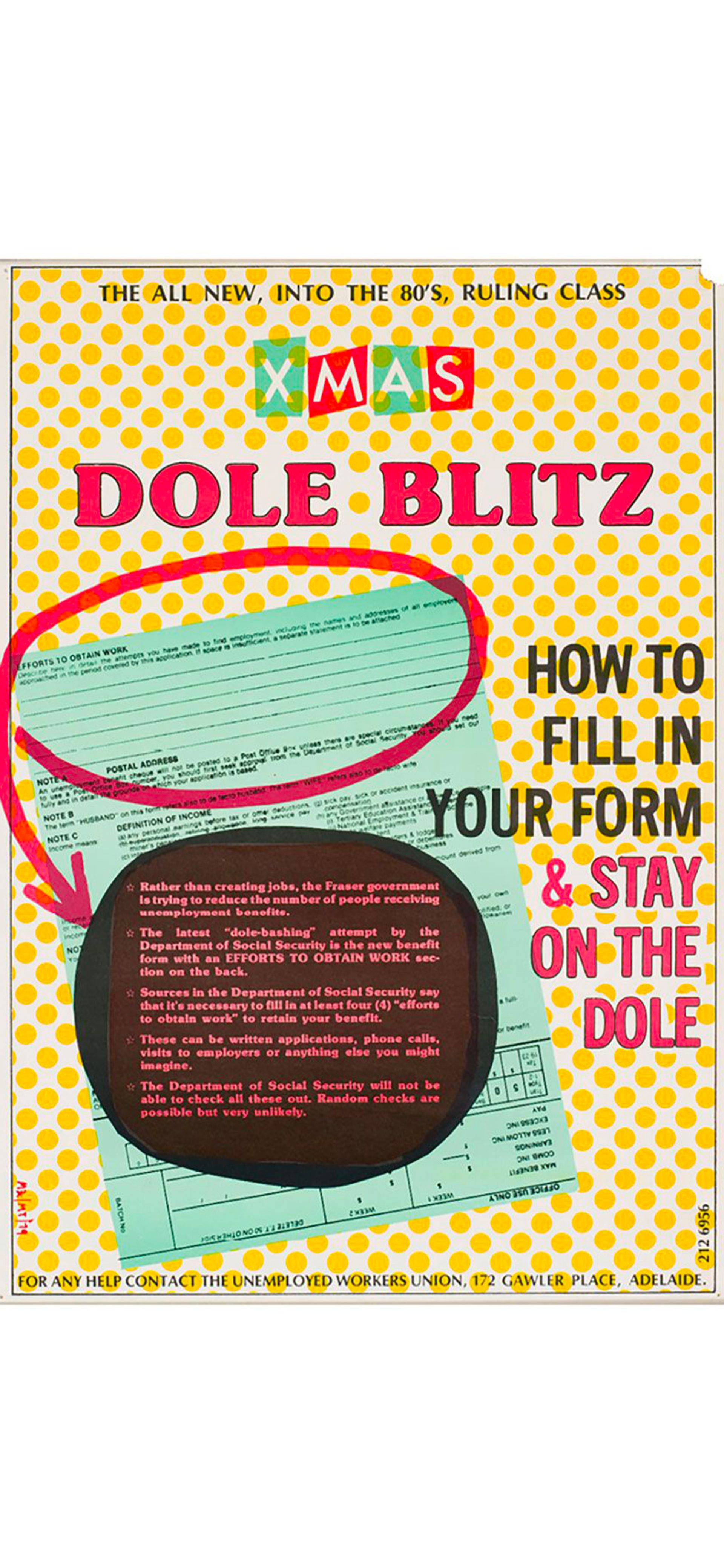

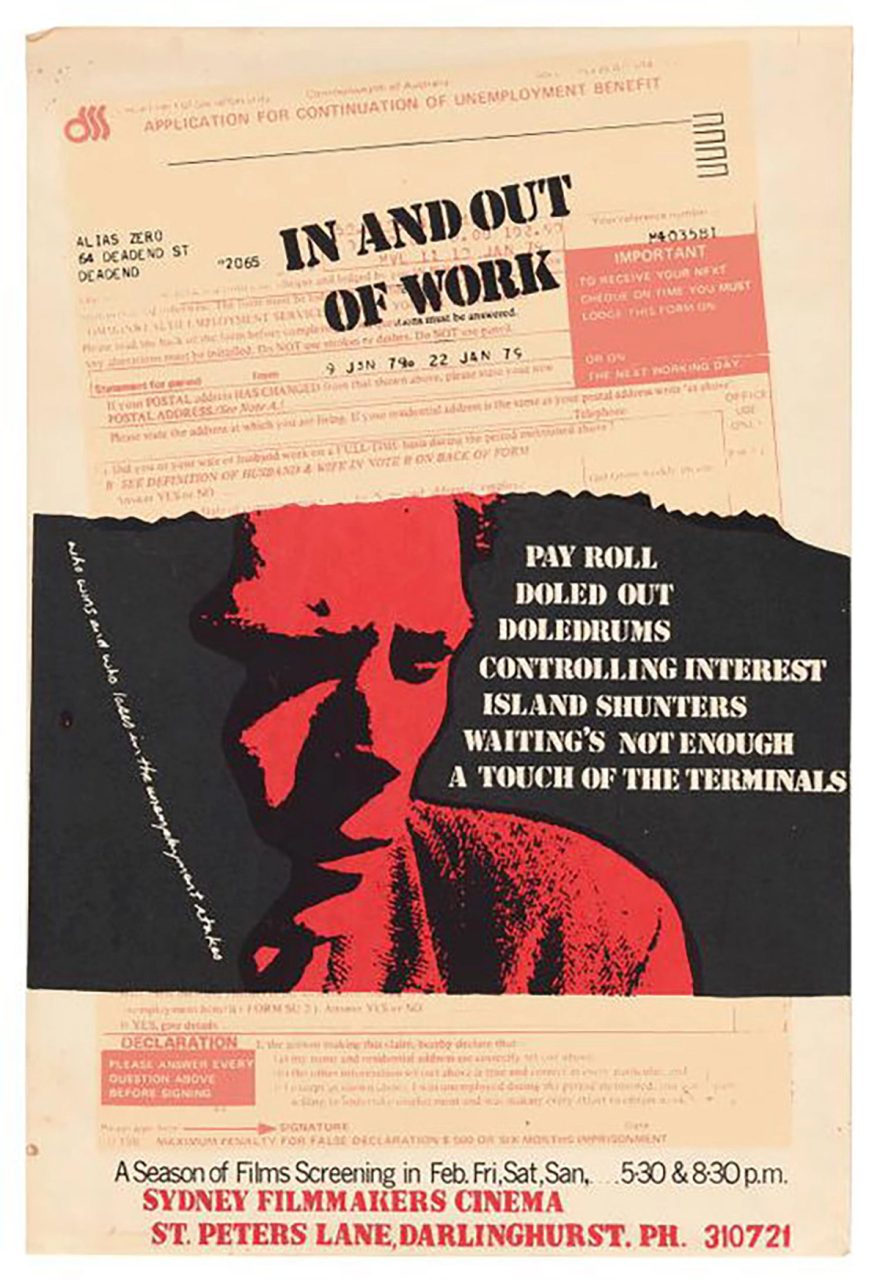

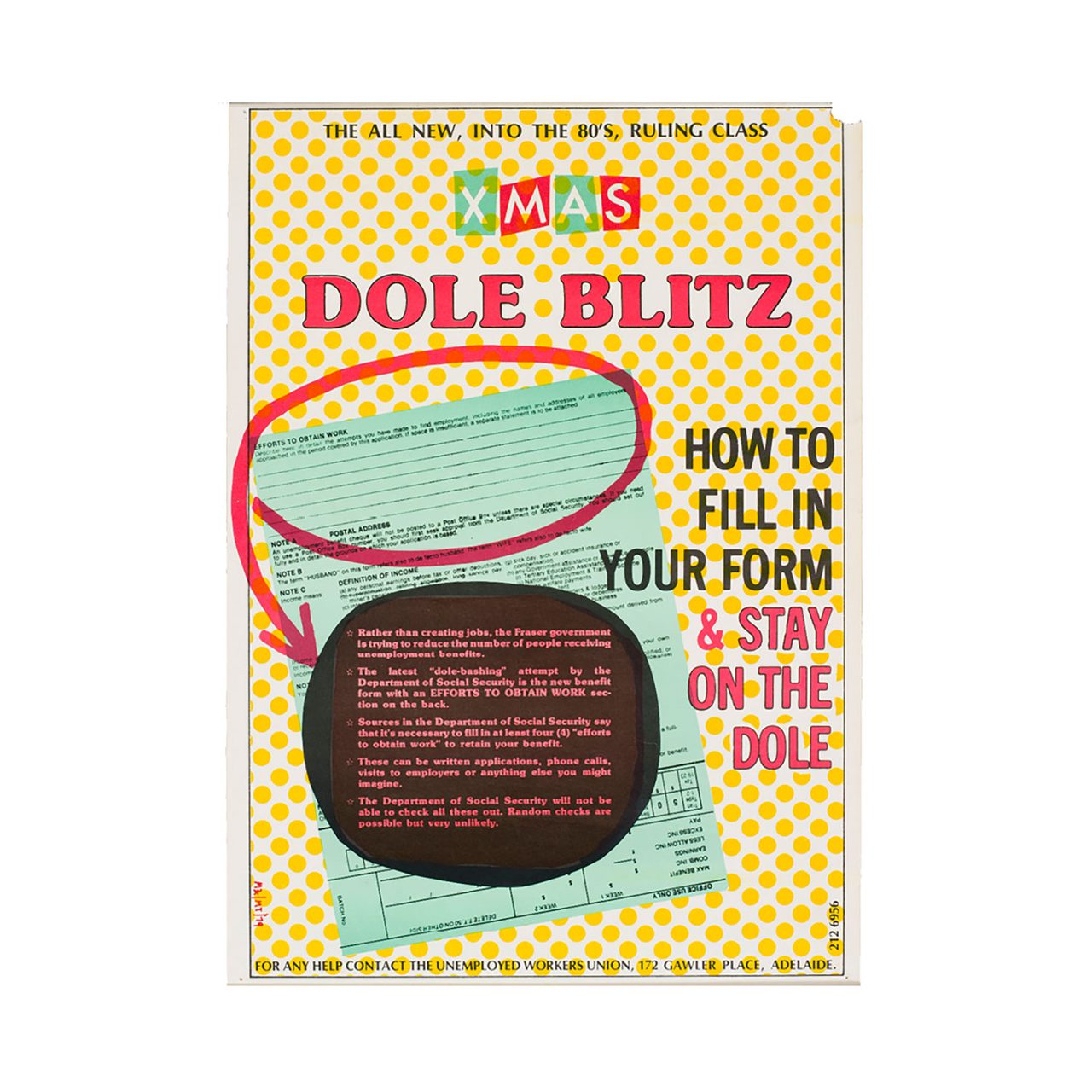

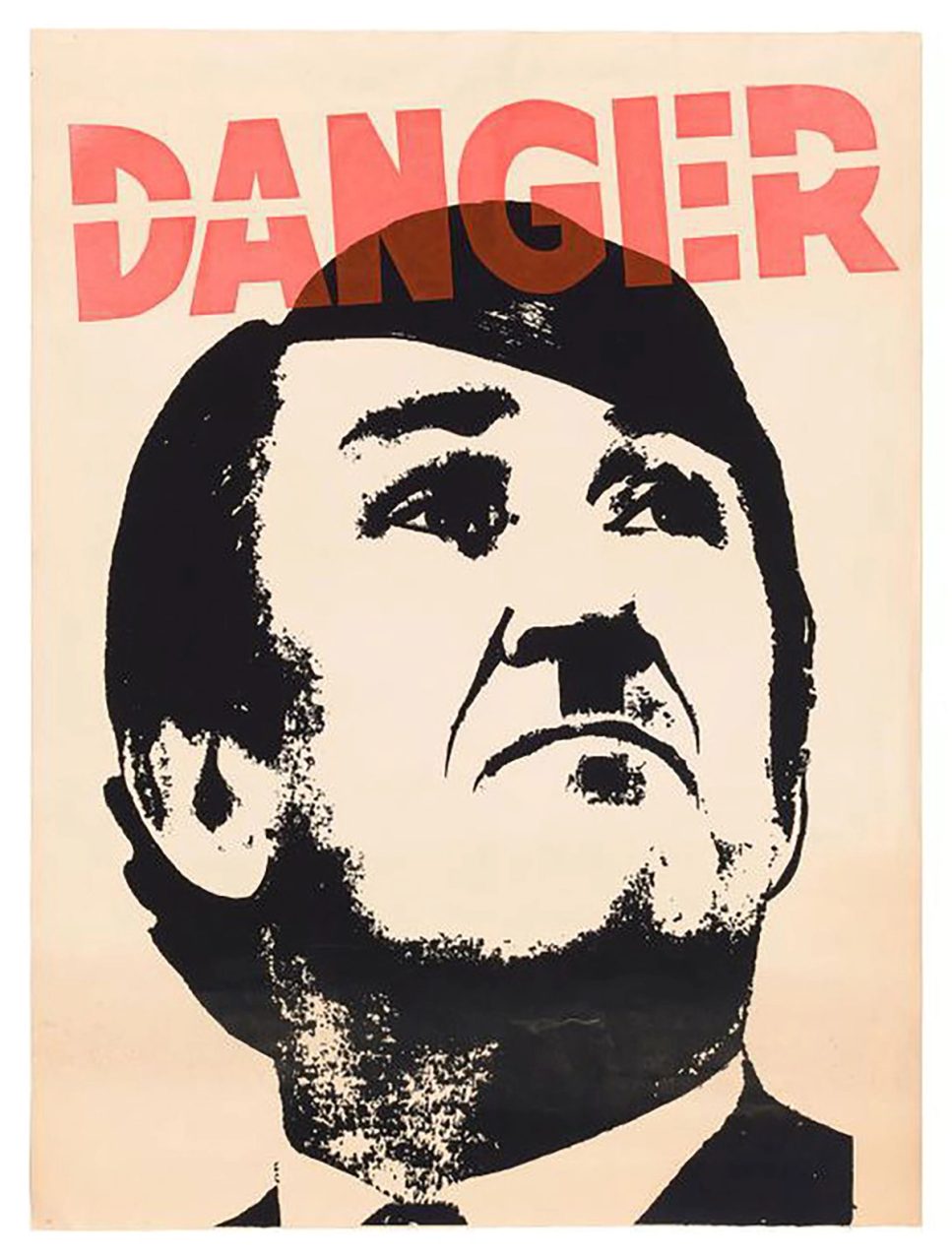

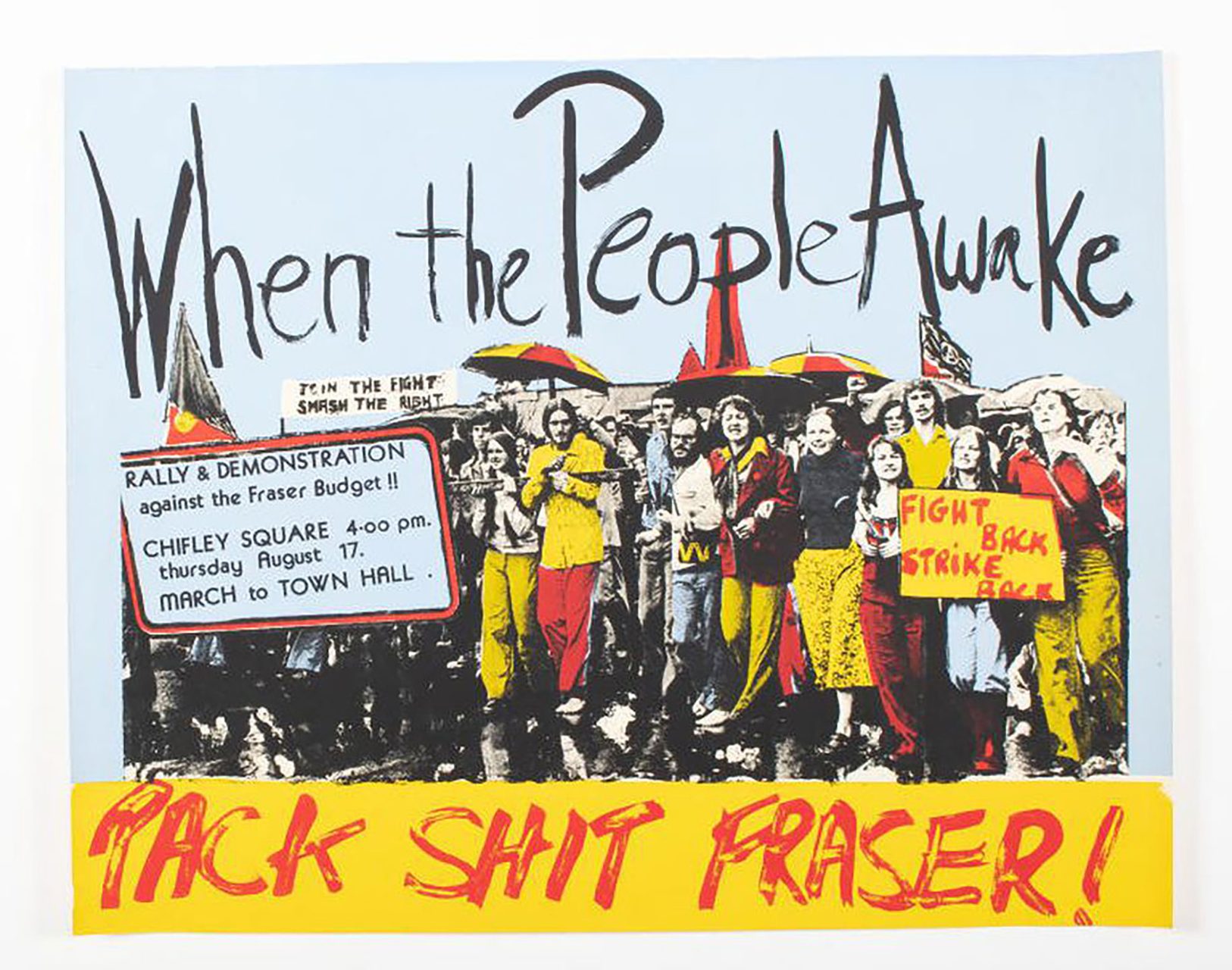

Mutual Obligation looks to unemployment activism in 1970s Australia to track the links between unemployed worker unions, the origin of the ‘dole bludger’, and the unemployment policies we live under today. Featured within this story are posters, badges and other paraphernalia created by unemployed workers movements since the 1970s found in the Powerhouse Collection.

‘The Dole Bludger of the Year in 1979 won a surfboard, suntan lotion and a six pack of beer; a send up of Fraser's paranoid vision of the surfing, beach bumming welfare cheat.’

Transcript

Sally Olds In 1975, the economist Milton Friedman was a kind of political theory pop star. That year, he embarked on a tour around the globe that included a stop in Australia. First, he met with Augusto Pinochet in Chile. Then, he boarded a Qantas subsidised flight to Australia, where his tour was funded by a Sydney stockbroking firm. He gave speeches in three capital cities. He met with politicians. He appeared on primetime television and the mainstream presses eagerly reported his ideas. Here he is speaking to some of his acolytes in America.

Milton Friedman What do you do with displaced 40, 50-year-old workers who, for practical purposes, really can't be retrained for another profession or put out of work?