The Persian Tar: A Living Instrument

‘It's a very classical Iranian instrument. It carries the whole history of the Persian Empire – the literature and all that we know about the history of this country. I could see that in one instrument.’

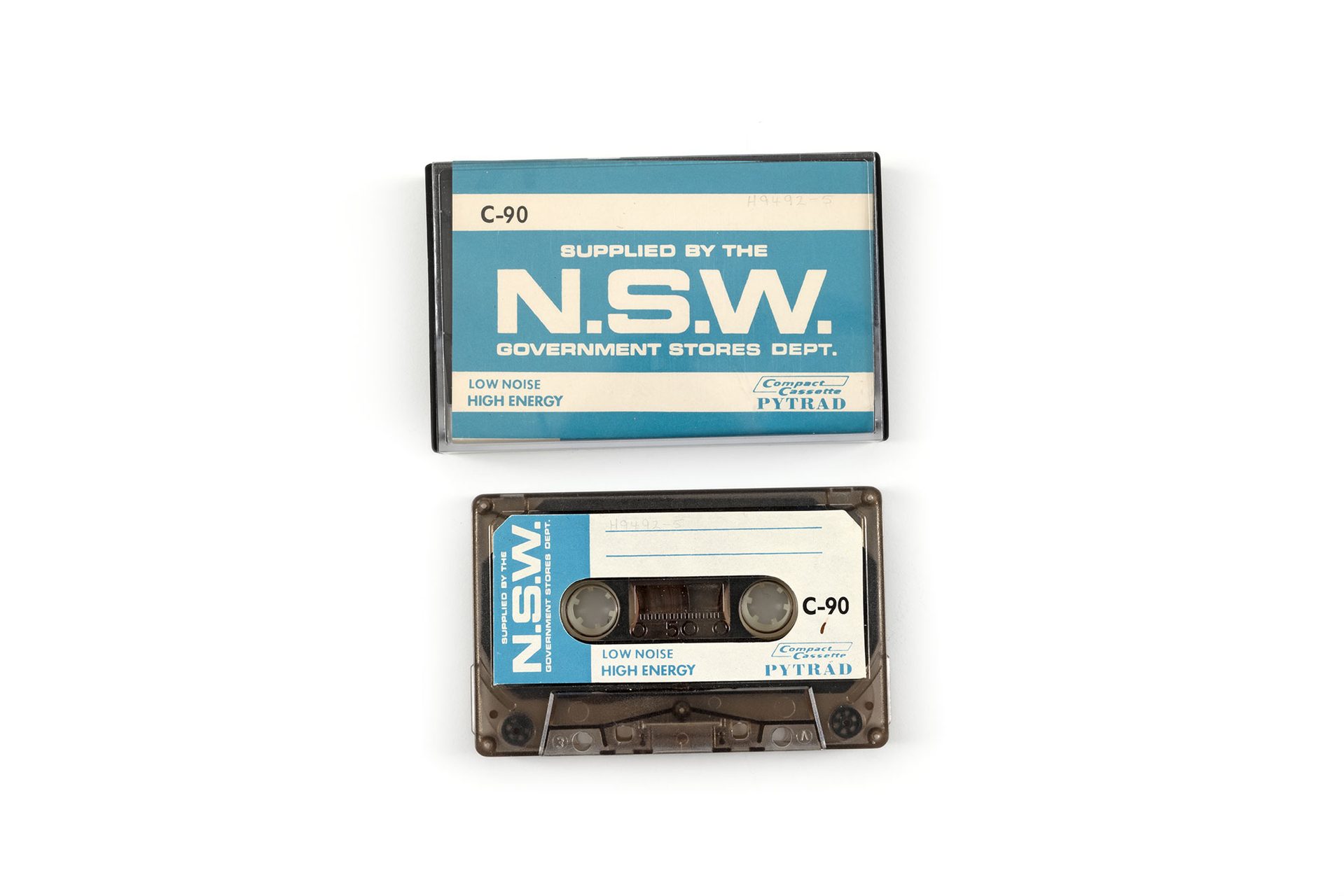

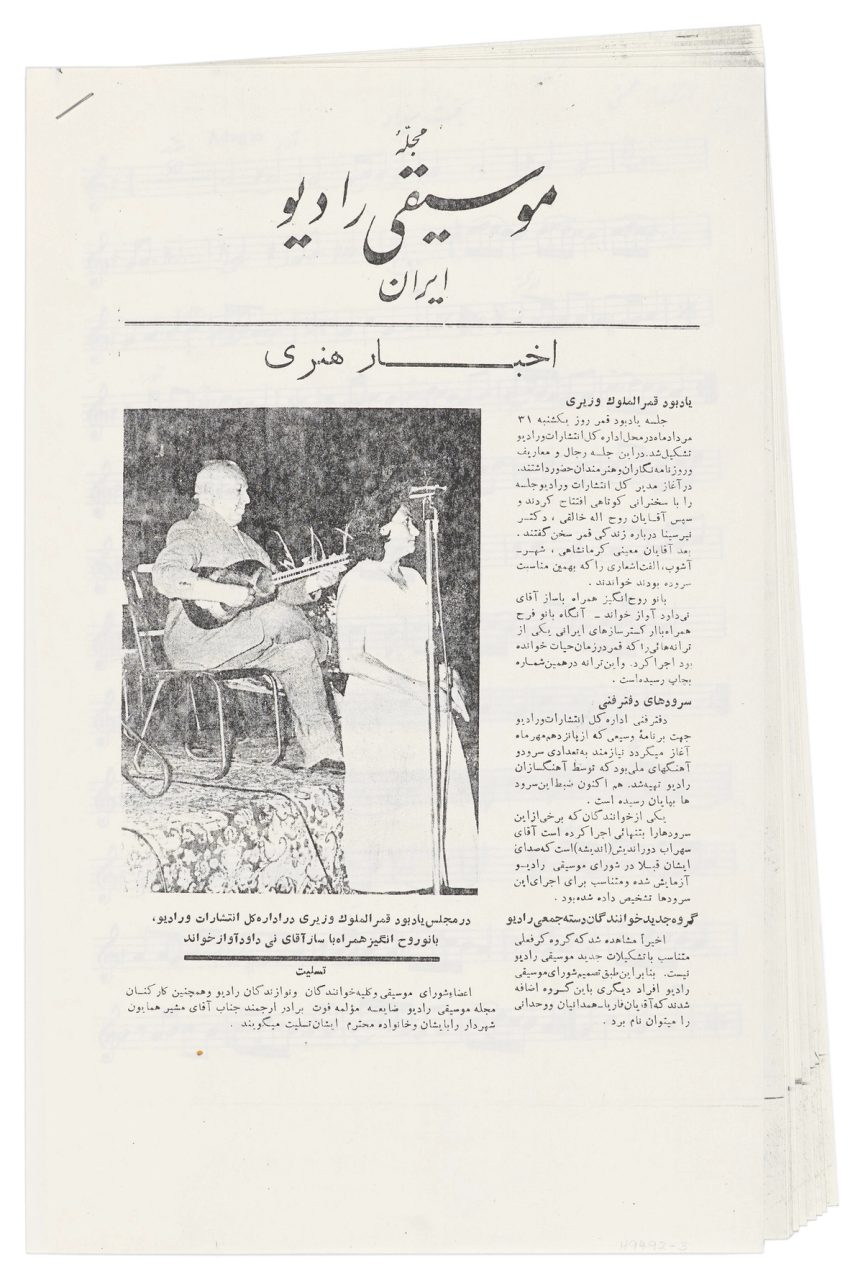

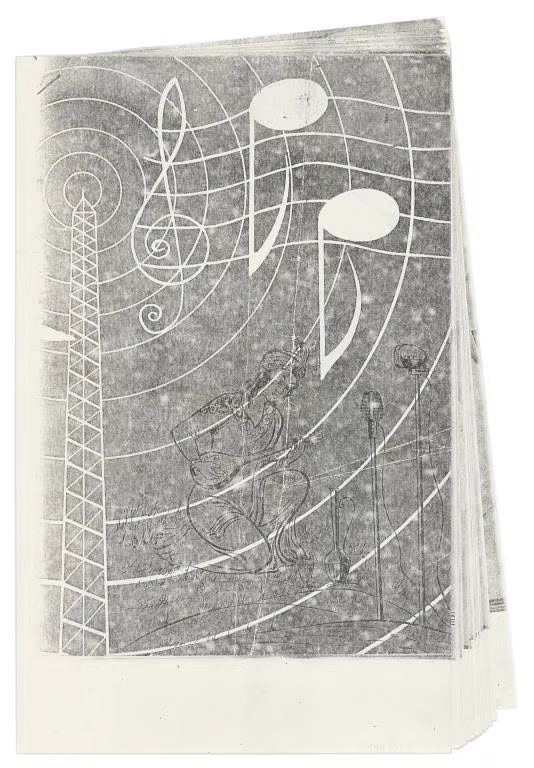

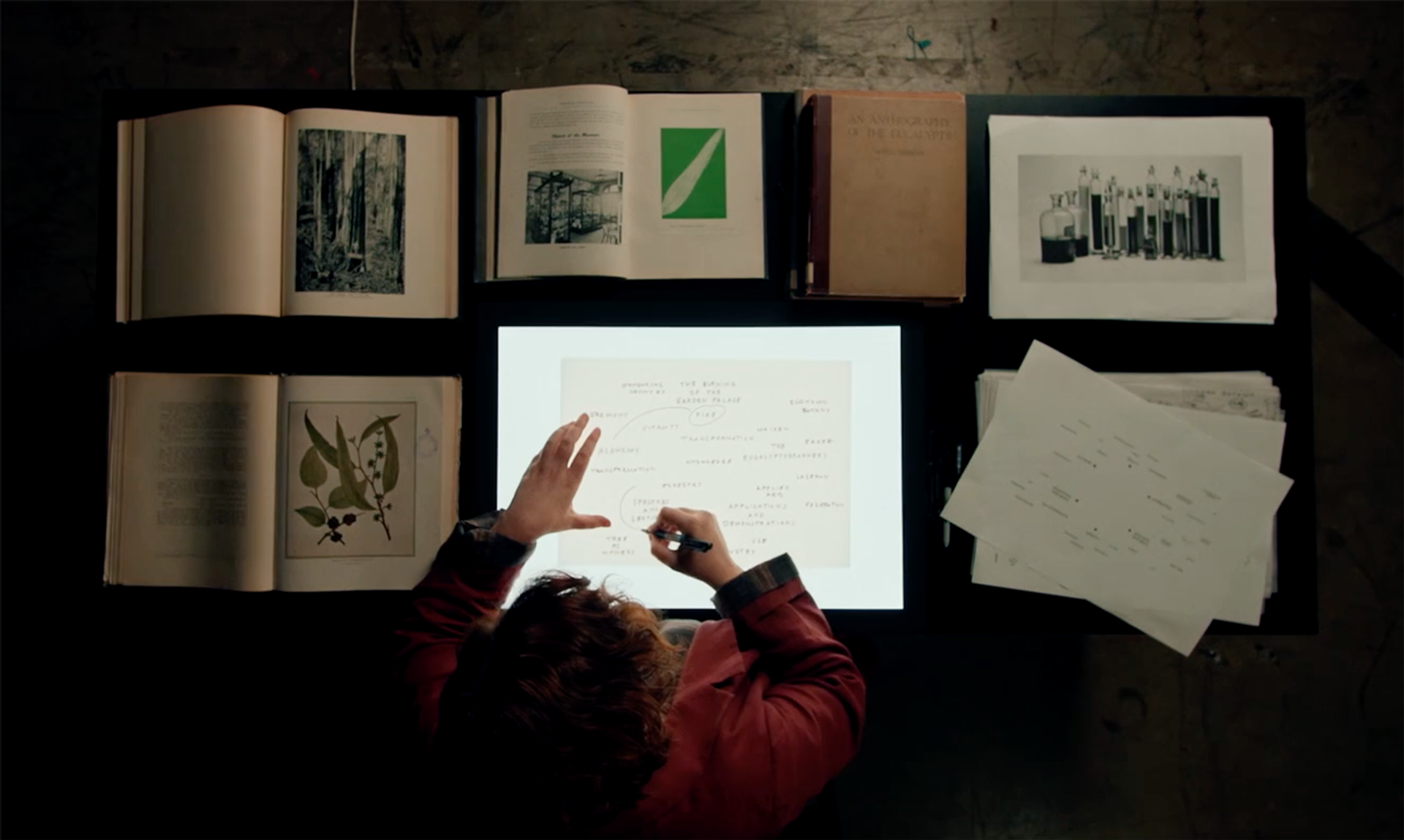

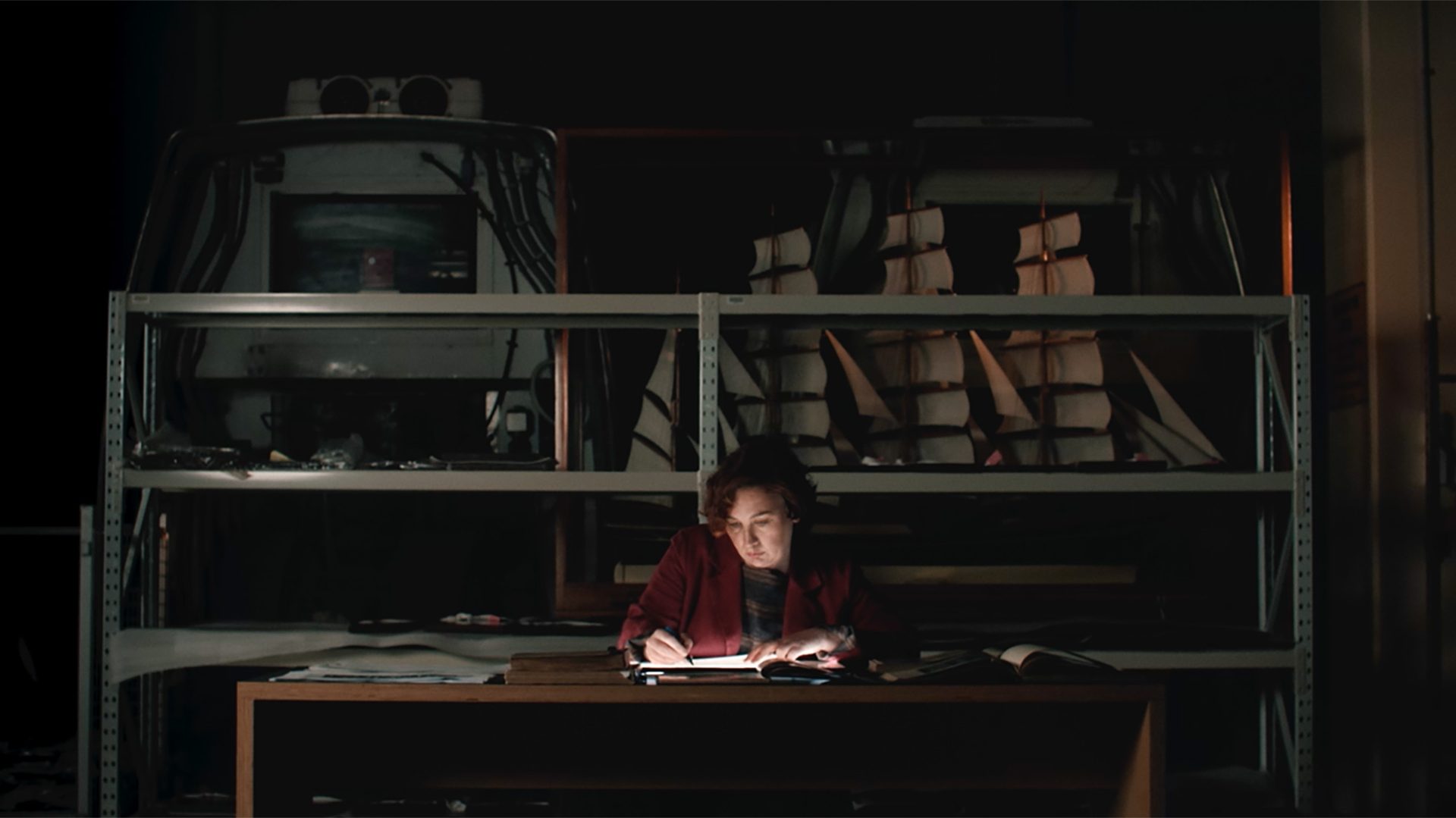

Musician Hamed Sadeghi examines the tar, a Persian 6-stringed instrument, in connection to his personal experiences and in the greater context of Iran’s rich classical musical history. Between 1956 and 1979, a radio program known as Golha, or Program of Flowers, broadcast new compositions daily, showcasing one of the most prolific periods of Iranian music in the 1900s. Much of the program’s output was lost, and while documentation is rare, traces of its influence remain in tape recordings and sheet music.

Learning to play the tar

The tar has a droning sound, but it is also a very melodic instrument. This instrument, it's got a storytelling character.

It's got a language that you have to learn, and you have to have a very strong relationship with the poetry. So, you get to read a lot of stories, a lot of poems, and you listen to a lot of singers and try to copy them on the instrument. You become the storyteller, with no lyrics, on your instrument.

A 1000-year design evolution

This shape of the tar that we see now is fairly new. It goes back only 250–300 years ago. But it did exist earlier. It was first seen more than a thousand years ago, somewhere in Shiraz, in Iran. It then got adopted everywhere else in the country and also Caucasia in Armenia, Azerbaijan, Turkey, and Afghanistan. But it kept changing.