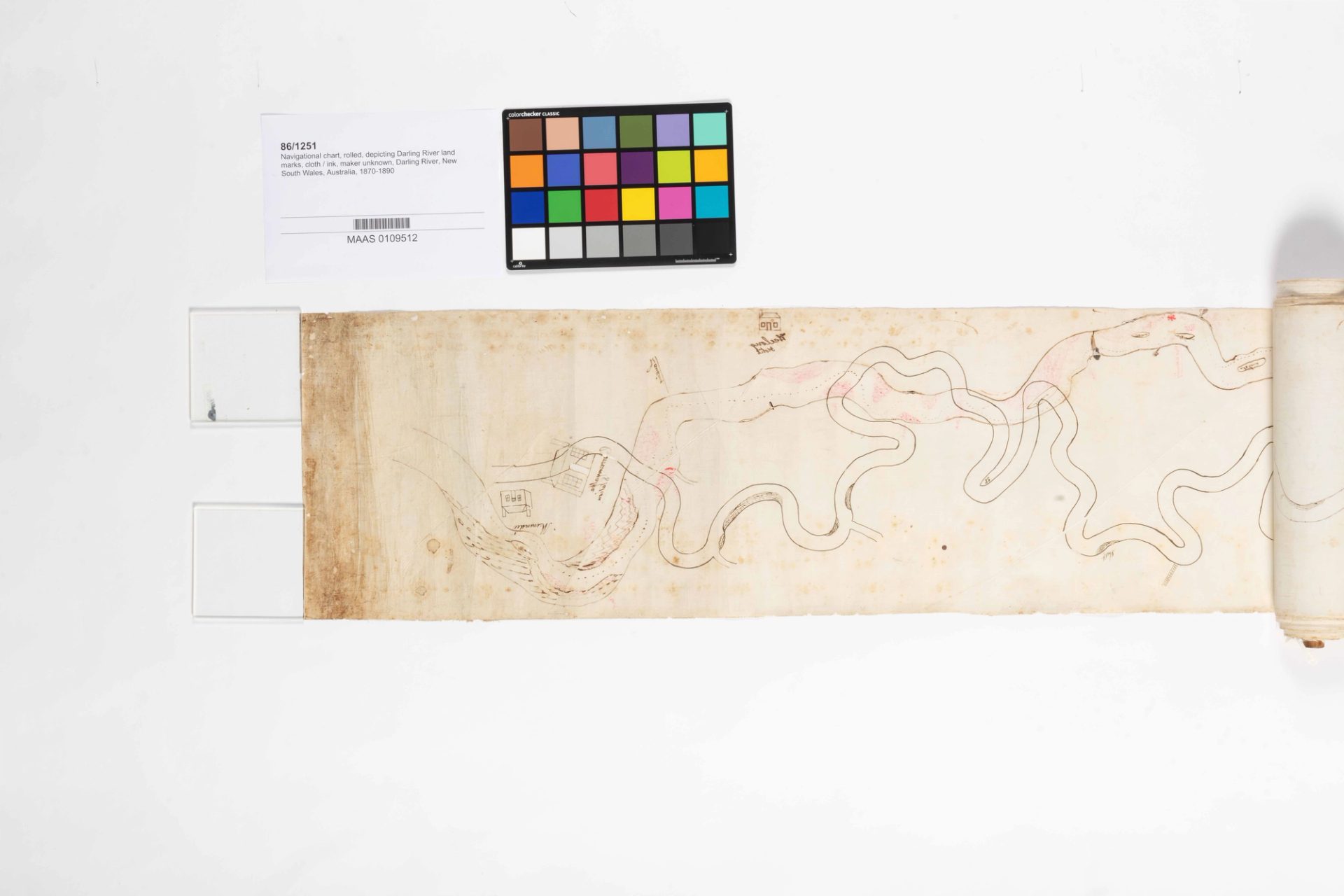

Digitising and conserving Powerhouse Object 86/1251

Since 2019, Powerhouse has been undertaking one of the largest digitisation projects internationally. Our ambition is to digitise the whole collection which is comprised of more than 500,000 objects. At 39 metres, Object No. 86/1251 ‘Paddle steamer captains’ navigational chart of the Darling River’ is one of the lengthiest objects in the Powerhouse Collection. It was repaired and digitised for the 2023 exhibition A Line A Web A World and is now accessible online.

Paddle steamer captains’ river navigational chart

The Barka / Darling is one of the longest rivers in Australia, wandering from its source near Brewarrina and Bourke in north-west New South Wales across roughly 1500 kilometres of mostly flat plains to meet the Dhungala / Murray in the south at Wentworth.

From the mid-1800s it was a major freight route across NSW with around 100 paddle steamers and barges carrying passengers, farm supplies and up to 40,000 bales of wool each year. But by the turn of the century drought and expanded rail freight services had put most paddle boats out of business.

Powerhouse Collection Object No. 86/1251 is a navigation chart, or river map, that was drawn and used by Australian paddle steamer captains on the Barka / Darling River in New South Wales between 1870 and 1890. The river’s course, landmarks, woolsheds, hotels and homesteads from Menindee to Wentworth were hand drawn on the chart in iron gall ink with notes about rocks and dangerous river sections.