Collection Digitisation

Come behind the scenes at Powerhouse Castle Hill and meet some of the people digitising the Powerhouse Collection.

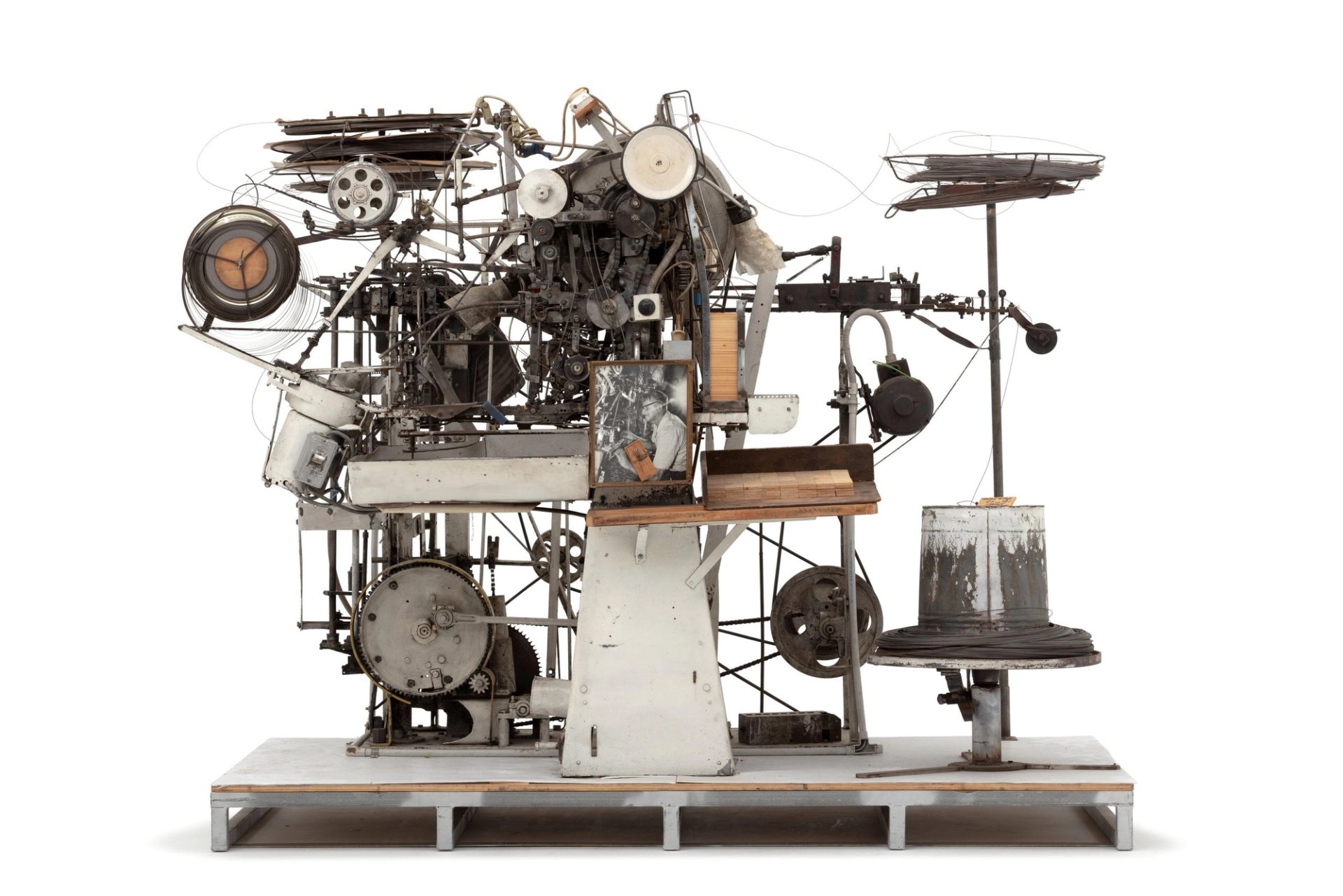

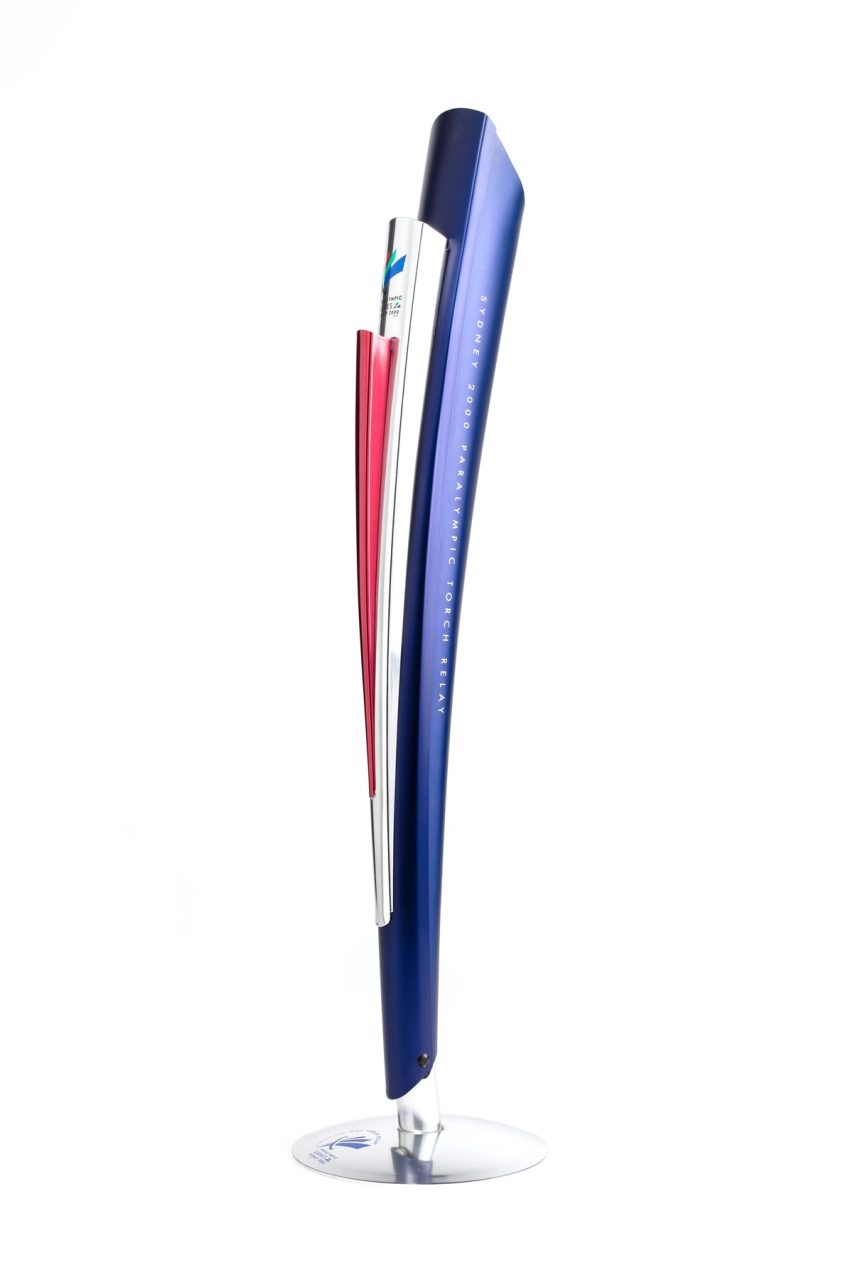

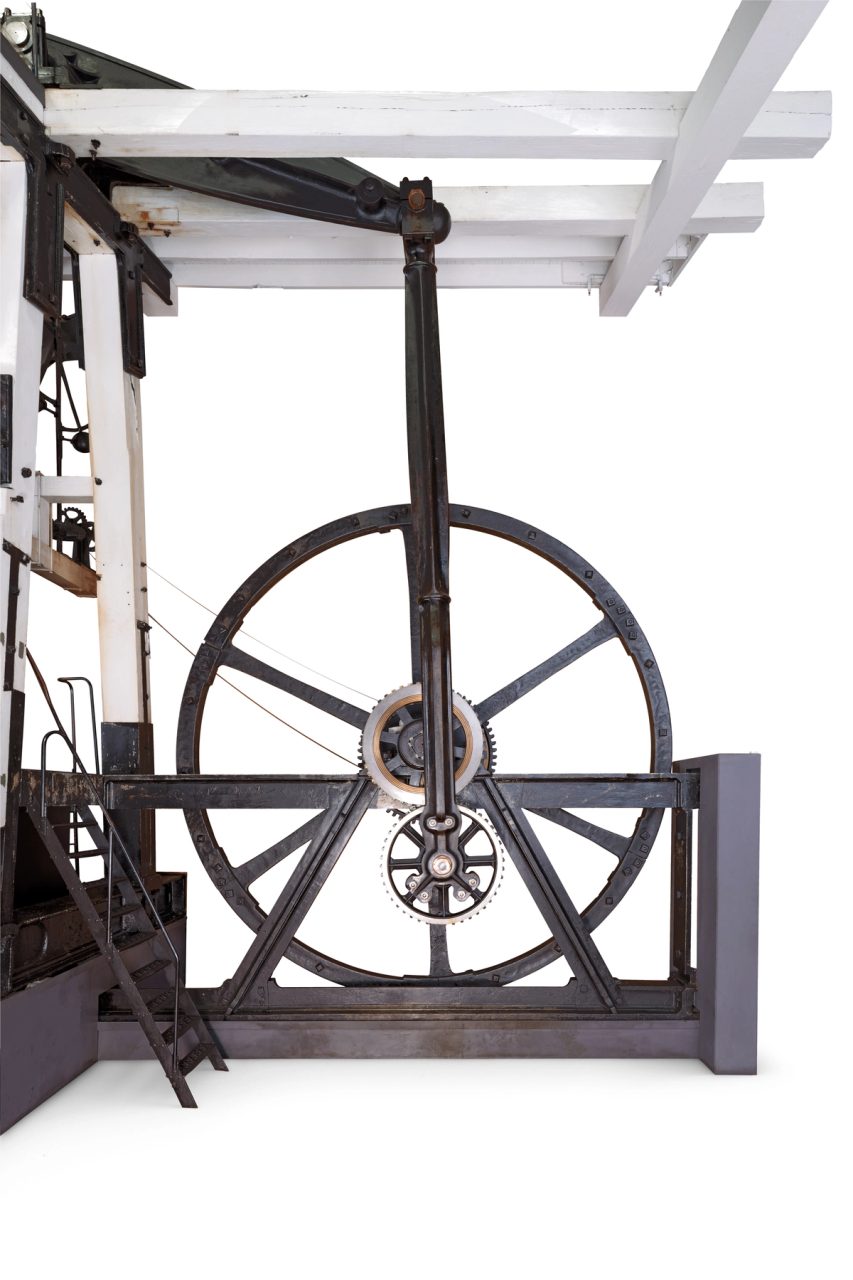

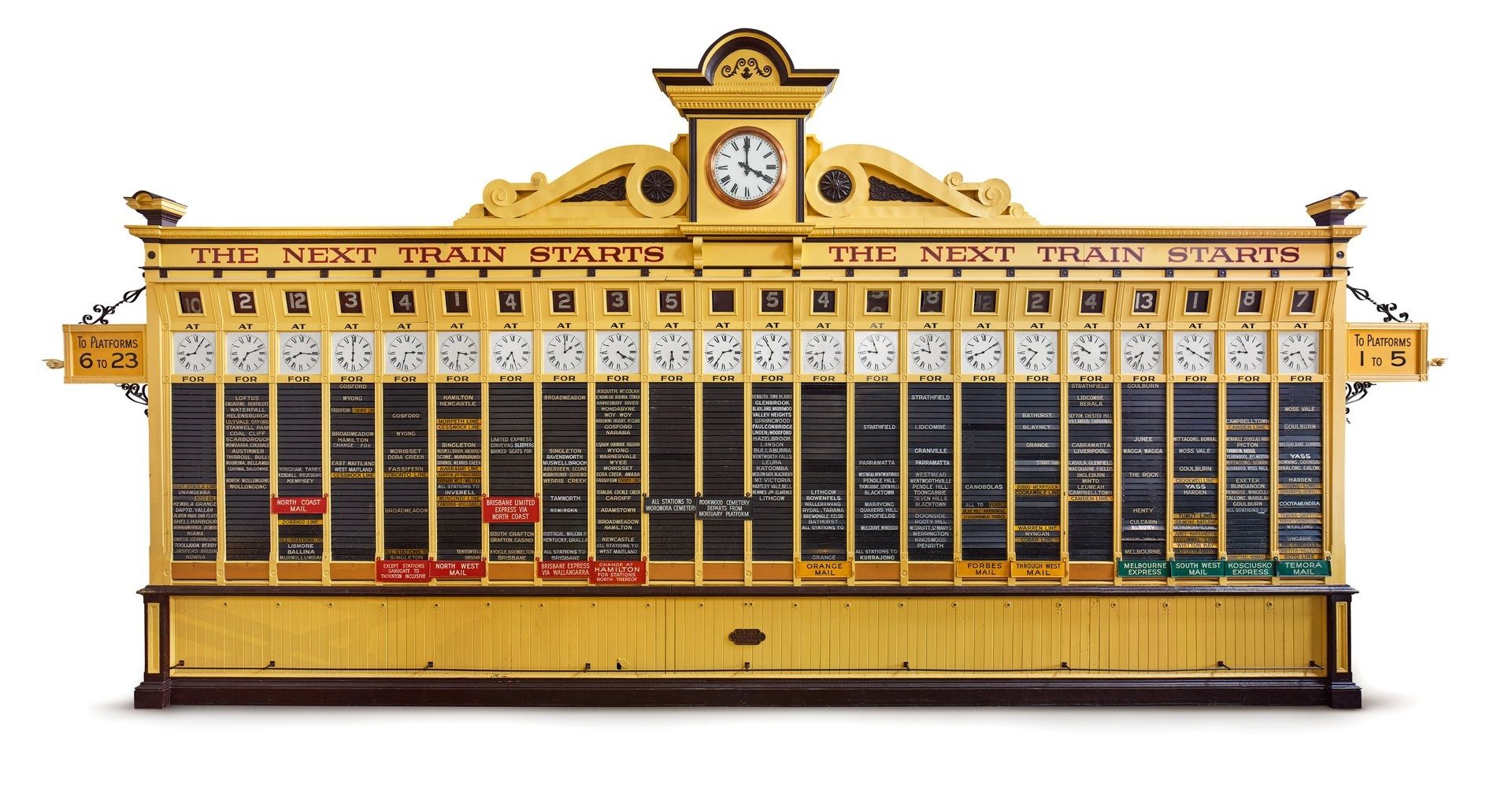

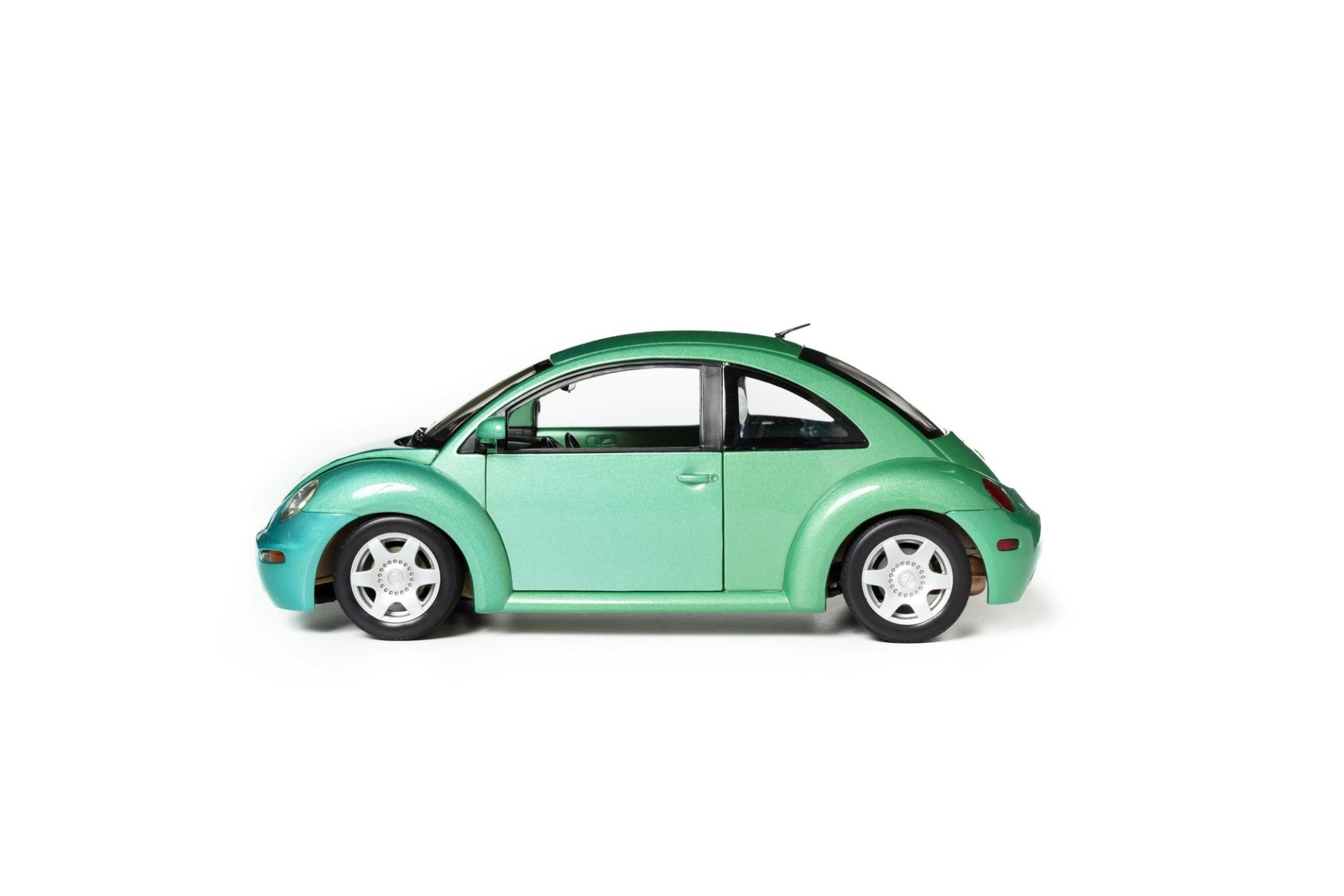

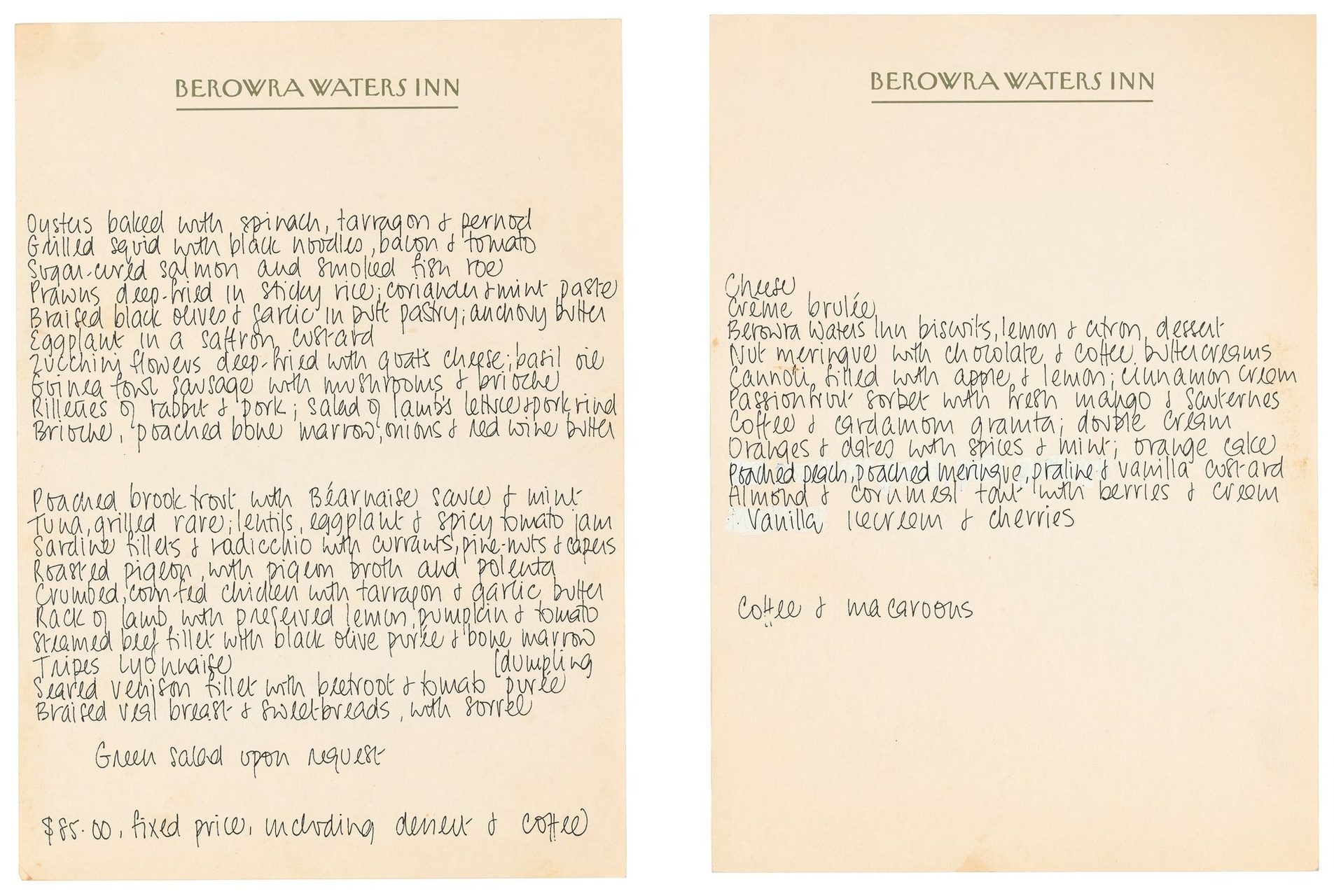

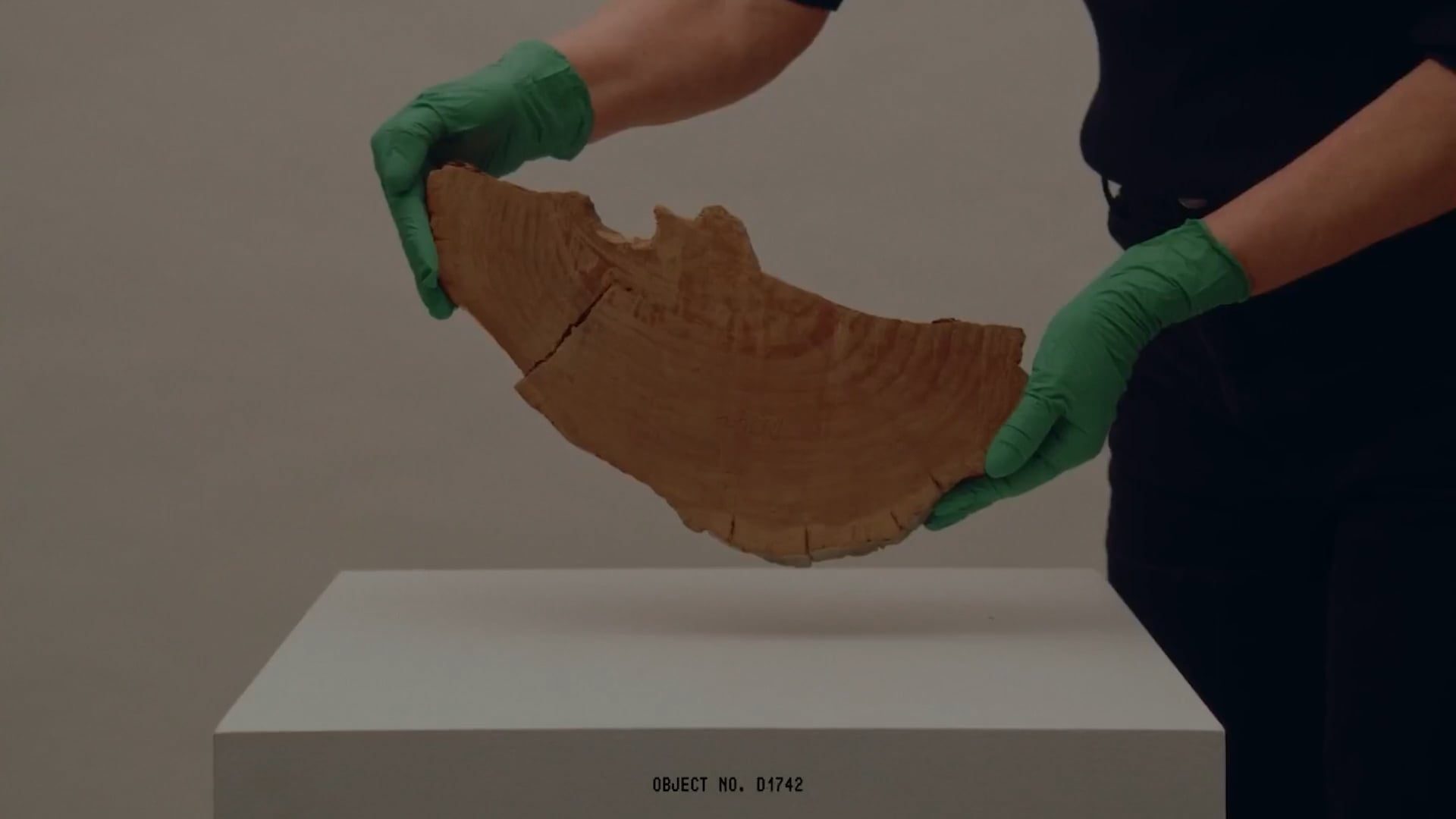

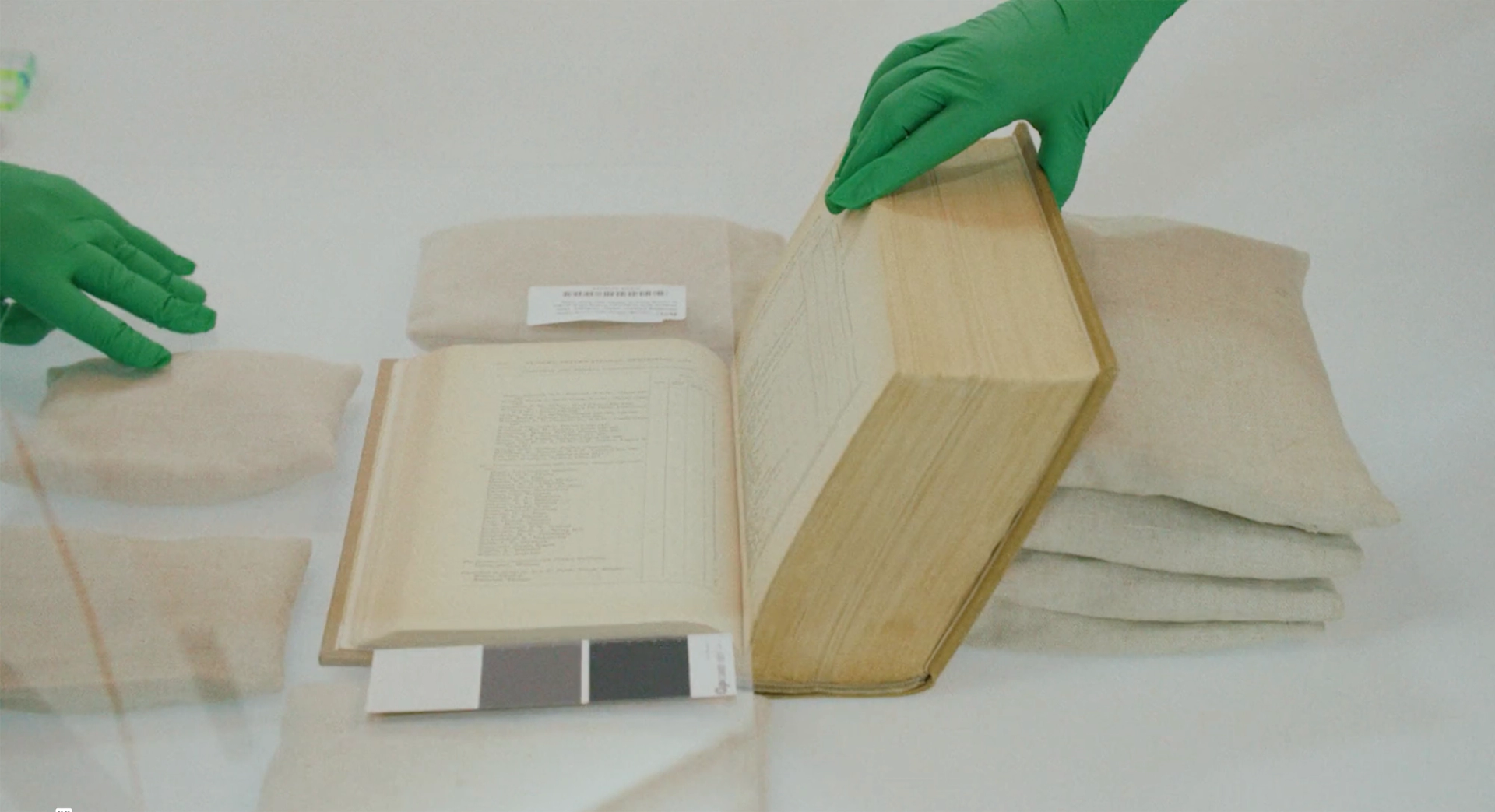

Collection Digitisation plays a key role in preserving and expanding access to the extraordinary Powerhouse Collection. The Collection Digitisation team consists of specialists with expertise in photography, registration and digital collection management who collaborate to create high-quality digital representations of collection objects. The digital collection is vital for conservation, research, programming, education, publications and access.

Nick Kleindienst

Manager of Collection Operations and Digitisation Projects, Collections Project

‘I’ve always worked in the cultural sector: I started as a creator, then worked in collection management for institutions in Australia and abroad, though what motivated a move to Sydney was the opportunity to work with the Powerhouse Collection — the history and materiality of the collection are second to none.

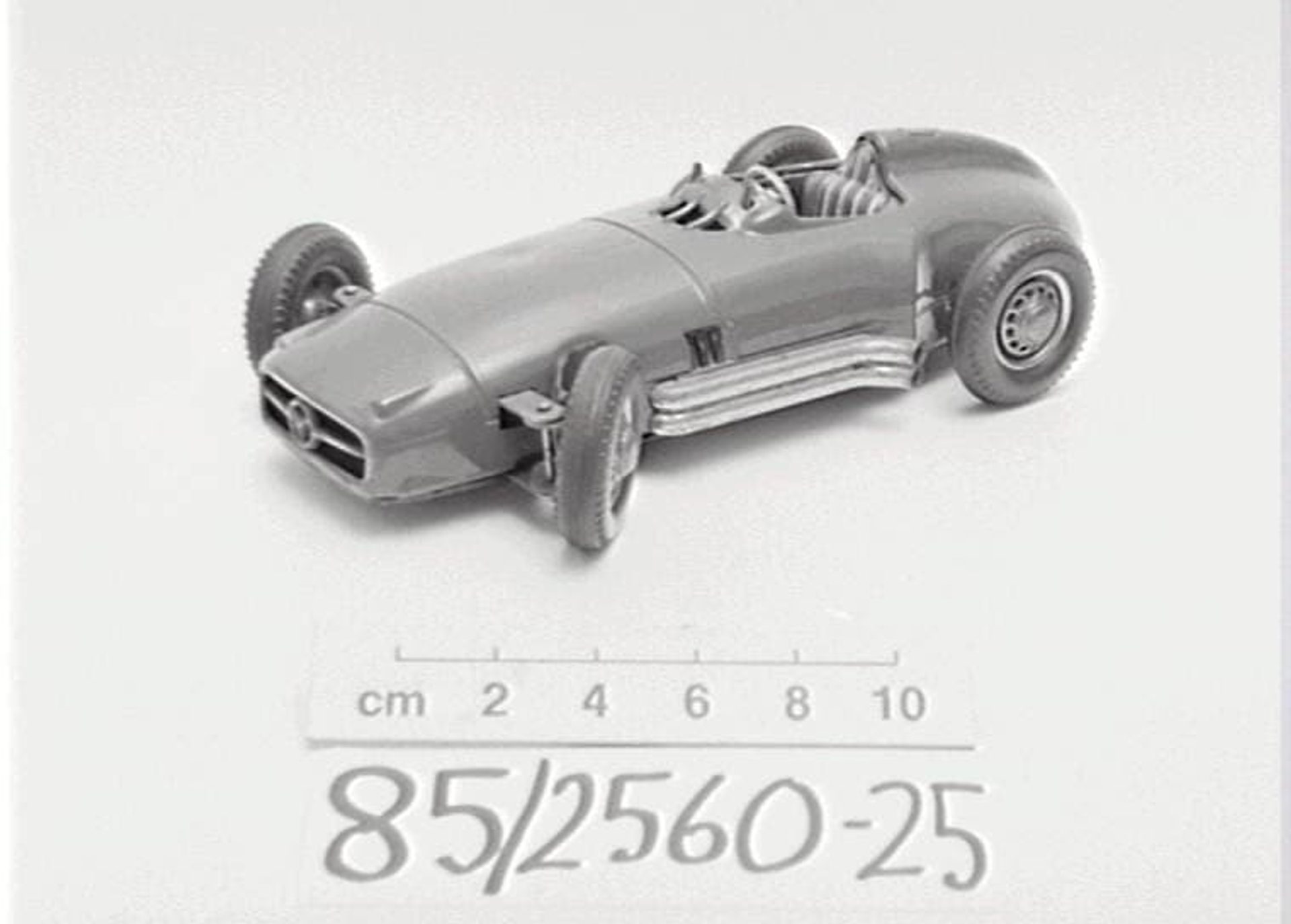

Our Collection Digitisation team builds on decades of museum imaging expertise, from the establishment of a dedicated photography unit in the 1970s to the museum’s Image Resource Centre in the 1990s, which produced more than 100,000 collection images.

In 2019, we launched our current digitisation project with the goal of capturing 338,000 objects. By the time the project concluded in 2024, we had photographed more than 360,000 objects, generating more than a million digital files. Today our team is structured into three key areas: photography, registration and digital asset management.