Telling Time

‘Time is the longest distance between two places.’

How do we tell time?

How do we mark time?

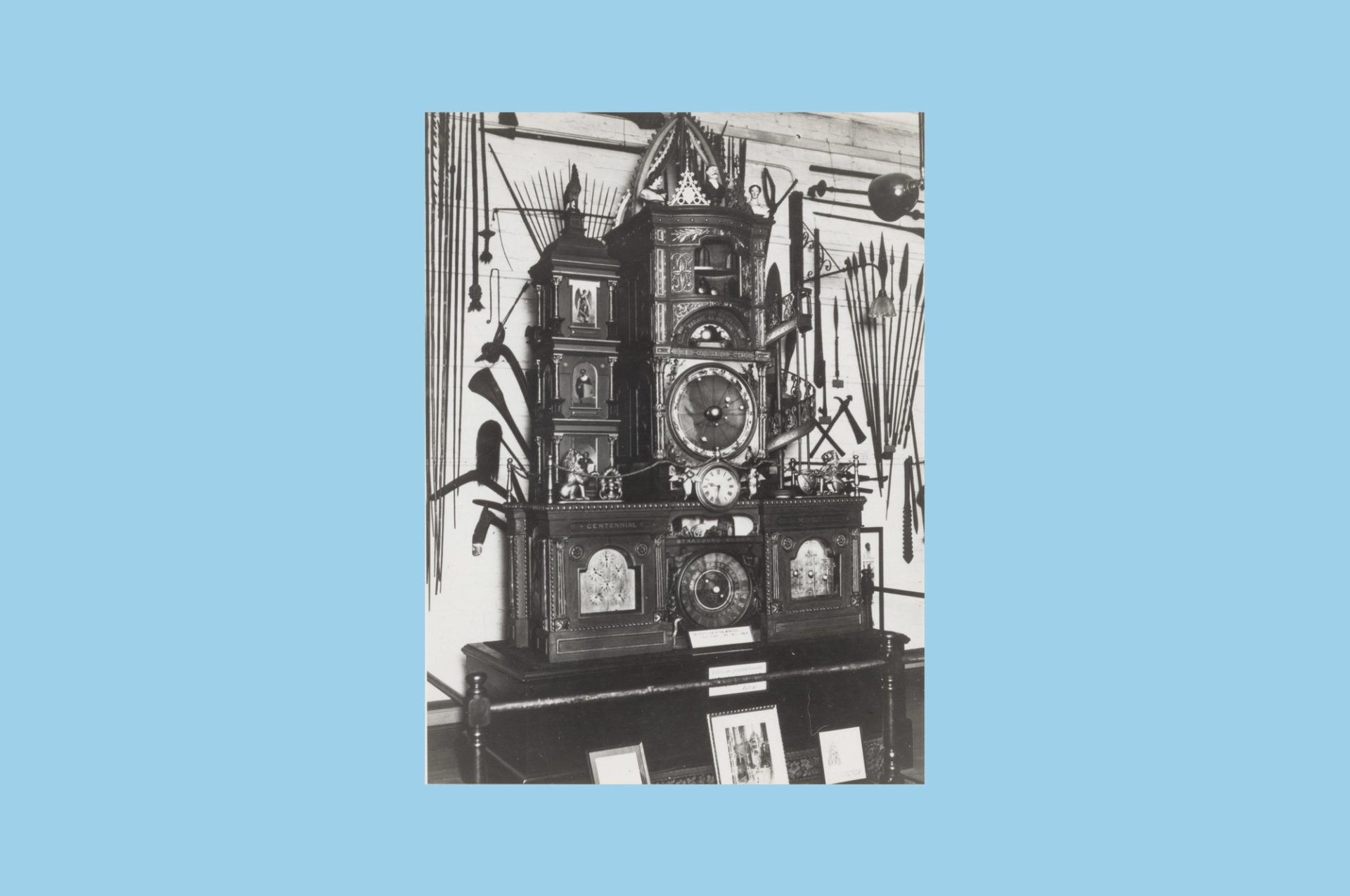

Is it with the tock and tick of a clock, the chime of the hour bell? Is it with the waiting for and the weighting of a clock’s pendulum?

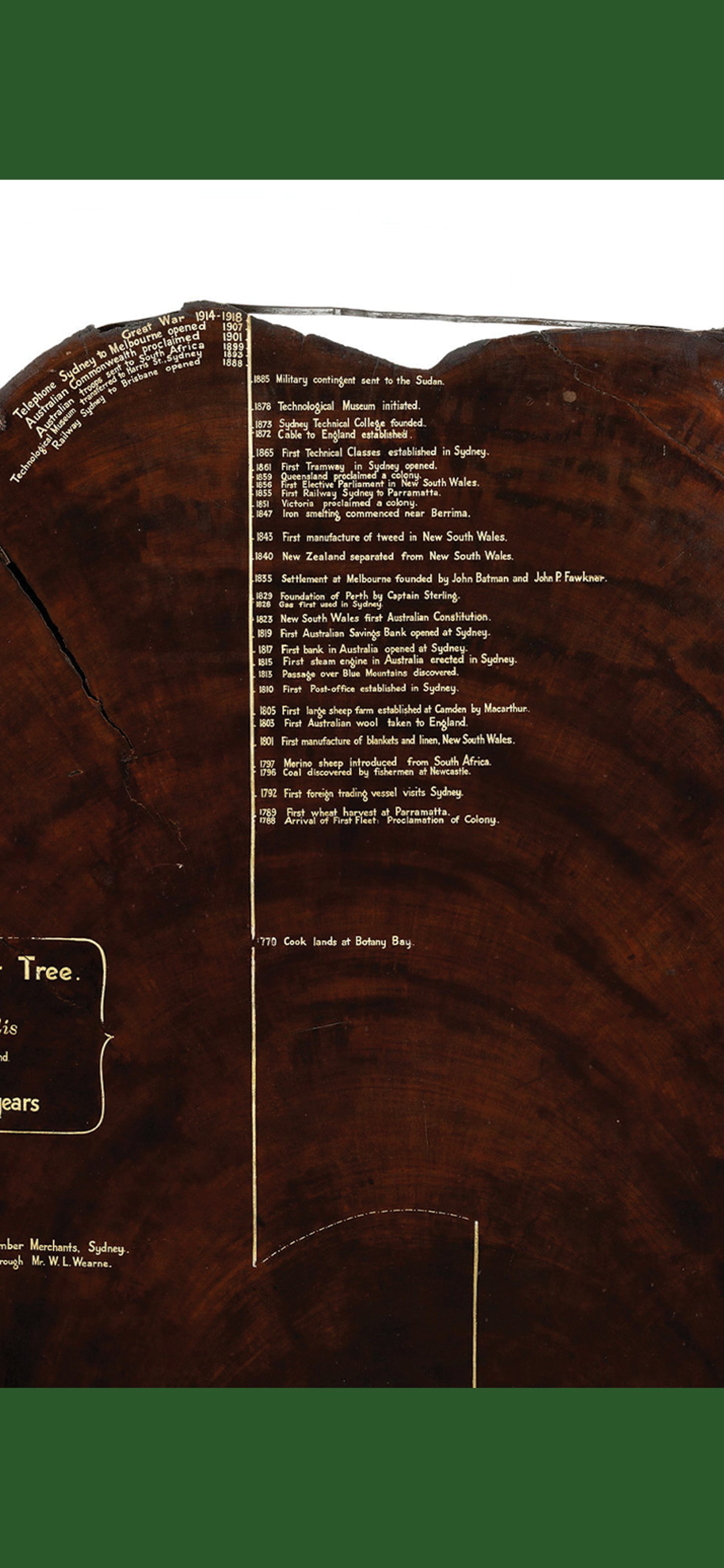

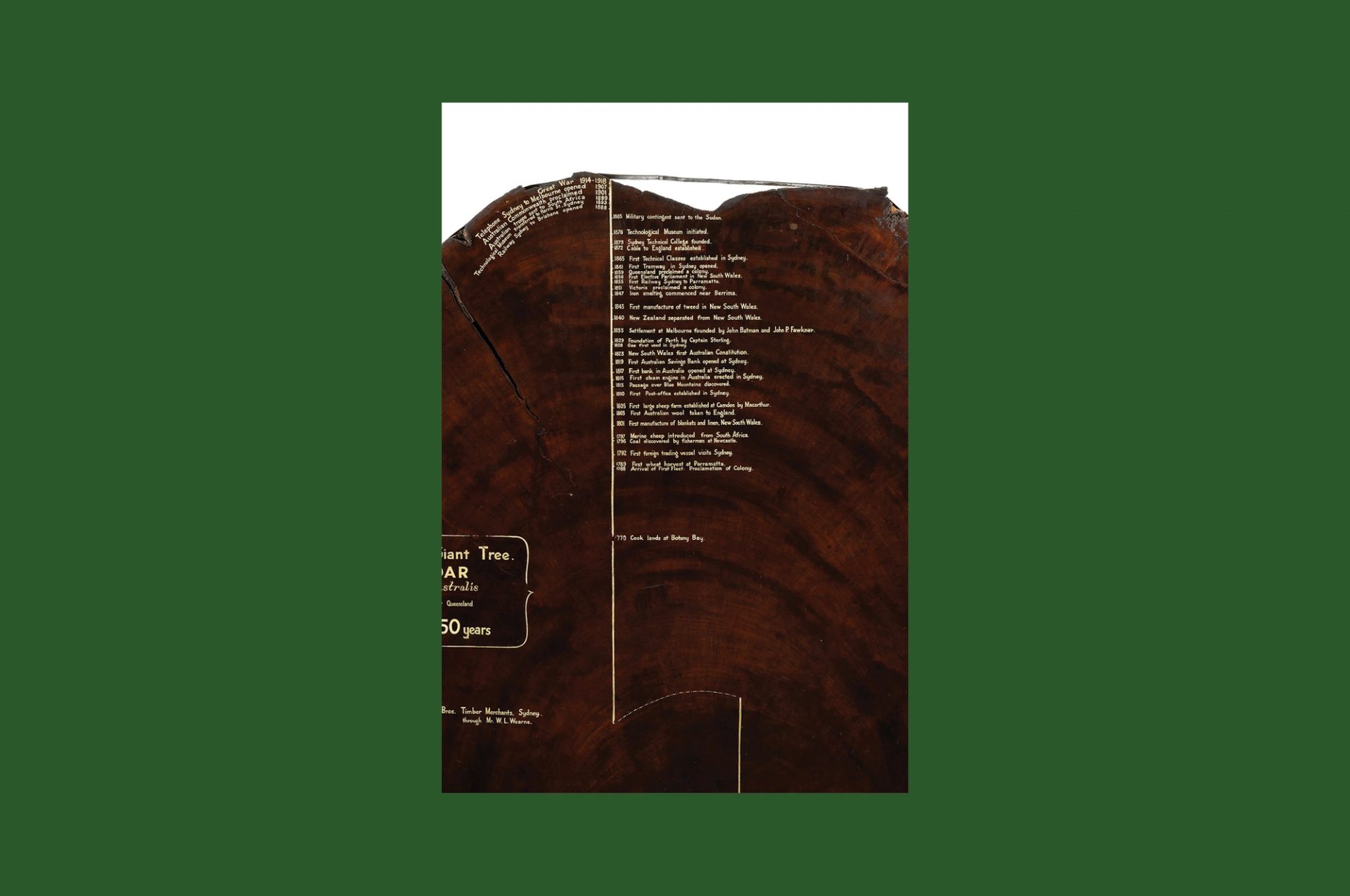

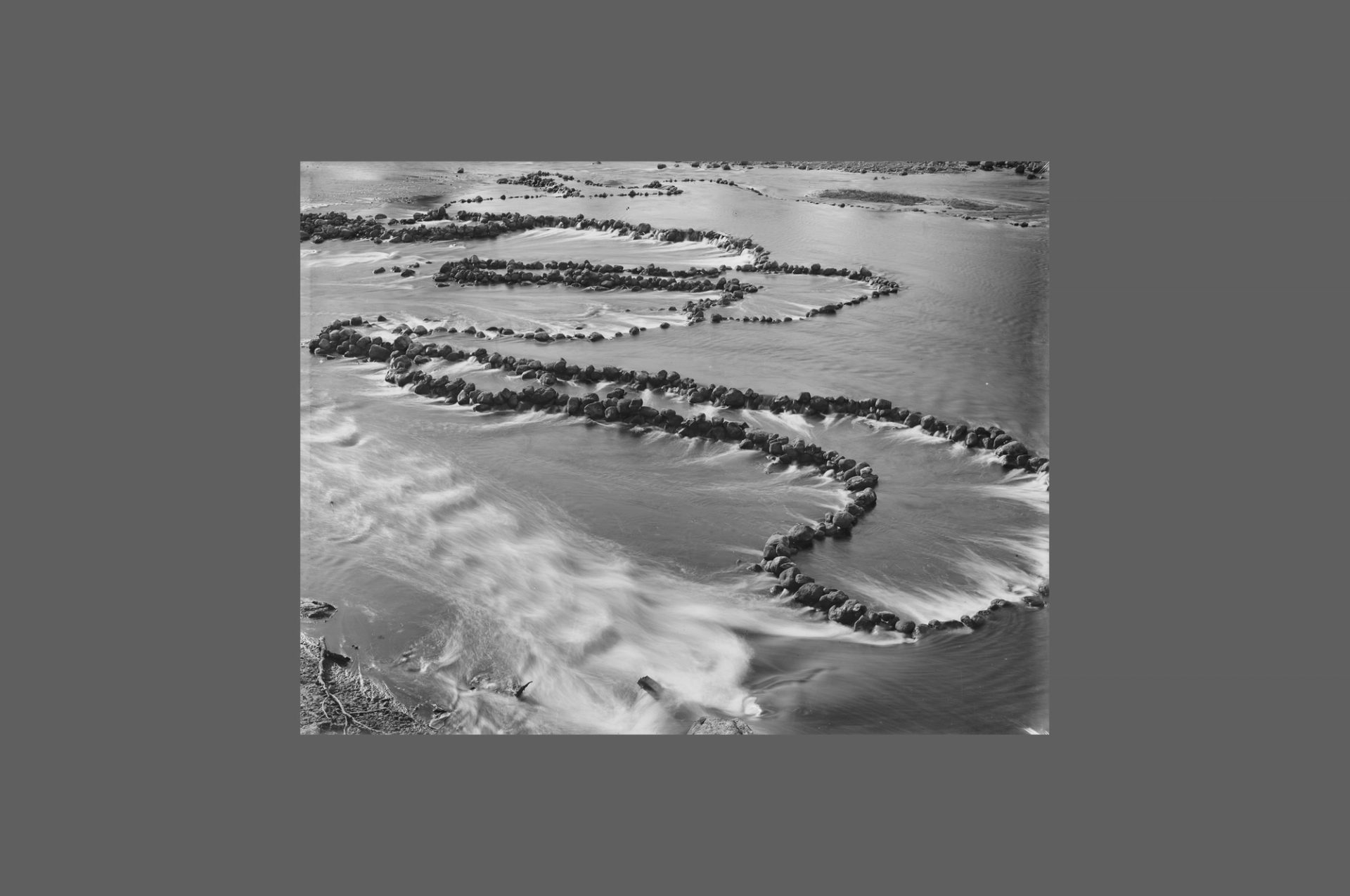

Is it with the growth rings through wood, every atom pulled from the ground and added to the tree’s girth, year by year an accumulation of weight and space? Is it in the distance we travel, from place to place, around and around, back and forth, the tick tock of our lives?

Or do we mark time with the sway of the bassist’s body, suspending us in a sonic universe where time is a note and the note must die for another to come? Do we mark time with song? Is a melody a slow unravelling of time’s gears, a surrender in sound? We sit inside a song and its time is our own; it is all the matter in the world.

And what does time tell?

What does time mark?

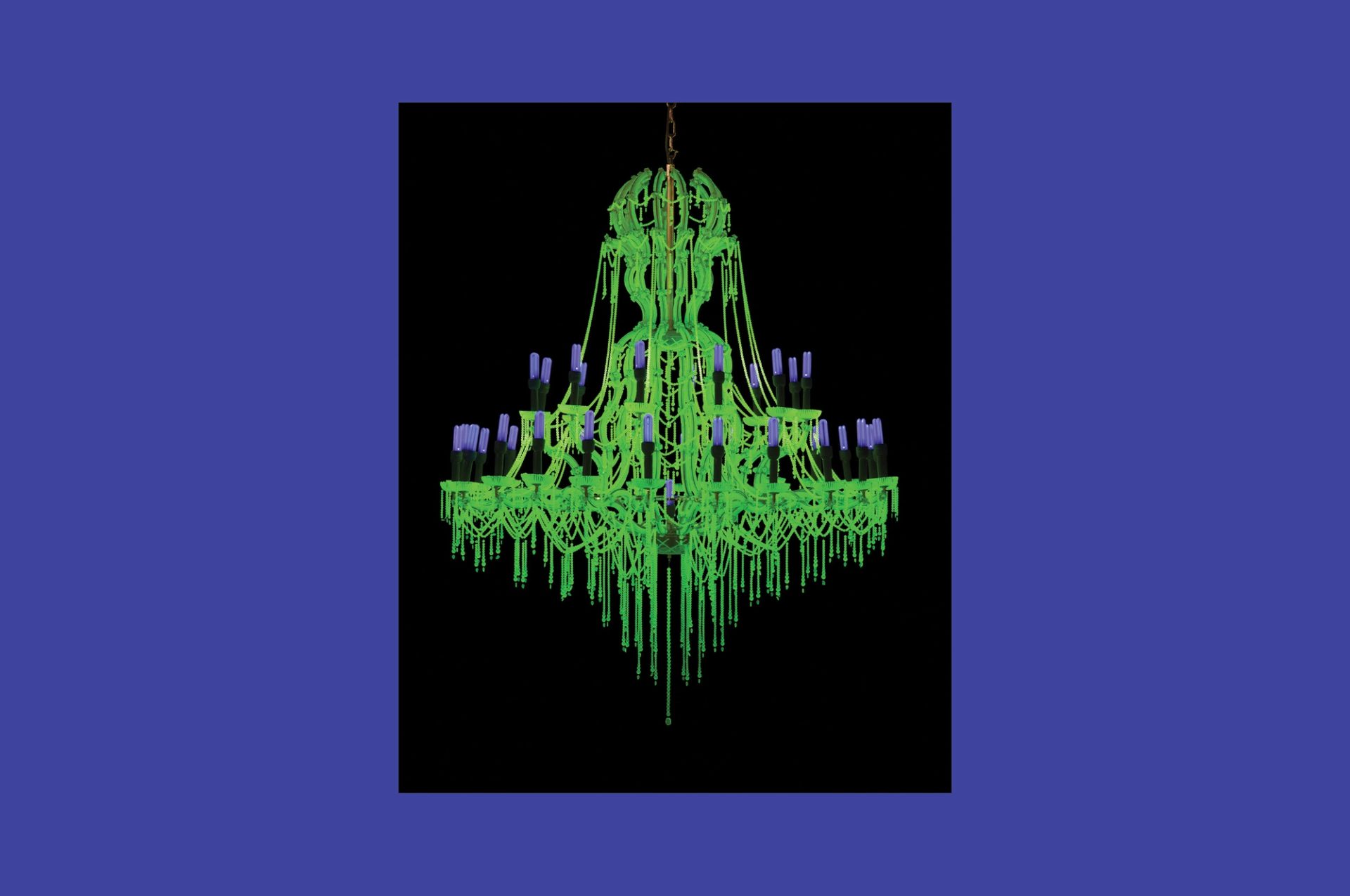

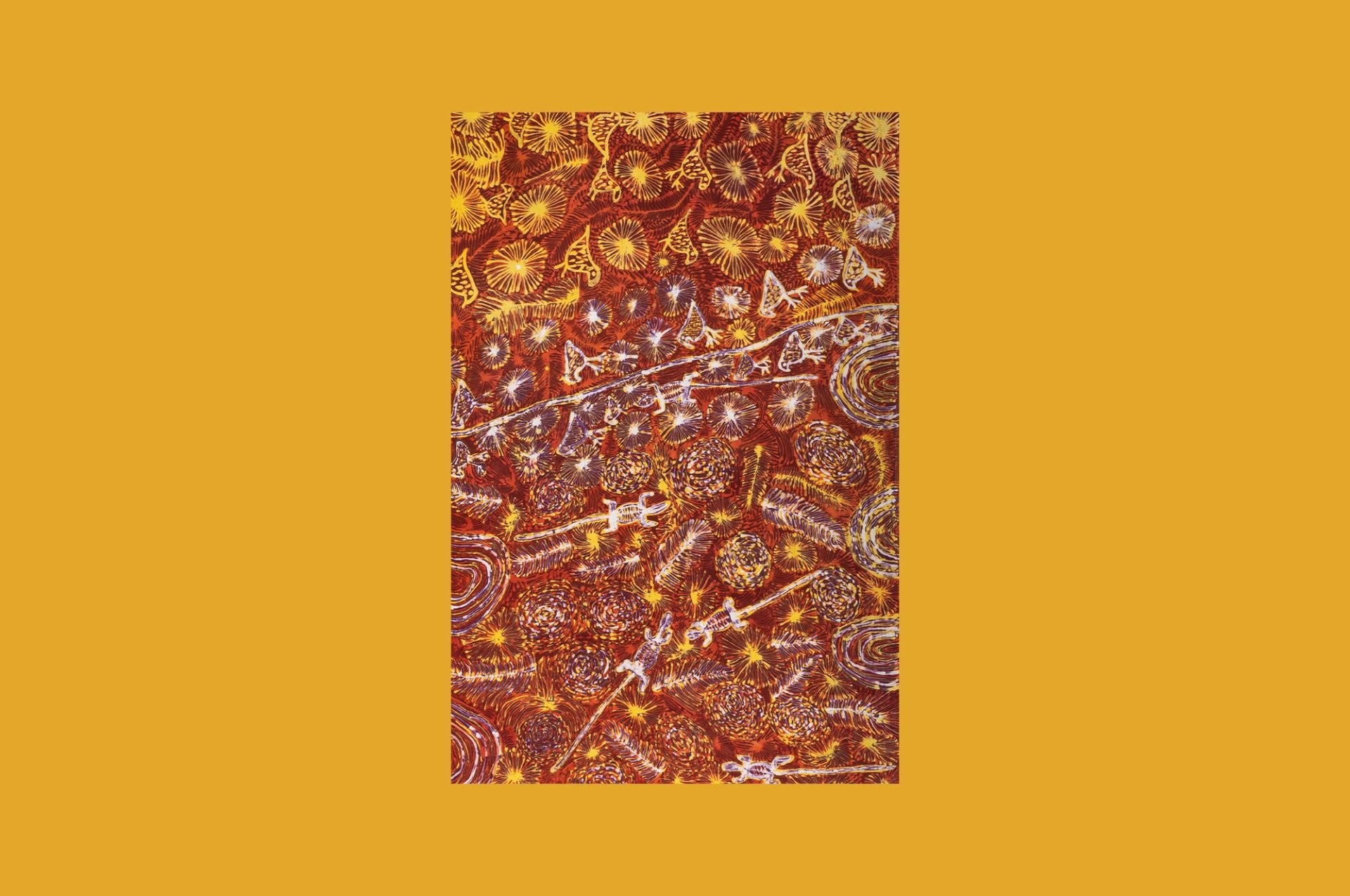

Three objects stand before us, all telling time in their own ways, all with their own marks of time, markers of the natural, the mechanical, the musical and the spiritual.

At the heart of this trinity is a wood specimen, a hunch from a red cedar tree 400 years old. Severed to reveal the years pushing outwards, a neat hand listing colonial events in straight lines across the curves of time. The writer starts a little rashly in the centre of the trunk, perhaps anticipating pithy events; more detail is added to the descriptions and the timeline shoves over to the left, a jolt in the space-time continuum. A polite reformatting, inviting other histories, other lists. Over time the cedar has splintered from itself, its weight no longer holding it together but tick by tock, gram by atom, wrenching it into a thick star. Here is a tree that has stopped growing and yet continues to transform. Time still makes its mark.