.BM The Boon Wurrung tree we were very fortunate to work with. Of course, N’arweet Professor Caroline Briggs AM and also David Tonia, they both agreed that we could become custodians at Monash University at Caufield campus. This happened at the same time as Tree Story or just before and we made a short film about going out onto Country and collecting the tree, going out with a crane, a truck, and delivering it to Monash and to MUMA for the purposes of not only the potential public art piece, but also for Tree School and Tree Story.

The significance of that tree, trying to understand how the probably small canoe that was carved taken out of the bark and the small coolamon, how that was made from the tree and how these cultural practices, I mean, this tree is potentially the small canoe or shield – most probably small canoe – and coolamon that was taken out of the bark would've been must probably precolonial. So, we're looking at a cultural material that's at least 200 years old, plus that in itself becomes a story. And so how that intersects with Tree School made sense. It became central in this interaction between peoples as well. And that sort of reiterated that idea of the agency of trees, the agency of Country.

AG-S Sophie also contributed to Tree Story with her essay, Spiralling, developed through the harsh Melbourne lockdowns. It's a series of vignettes that jumped through time and space at once, tracing a history of Sophie's relationships with trees and sharing her embodied understanding.

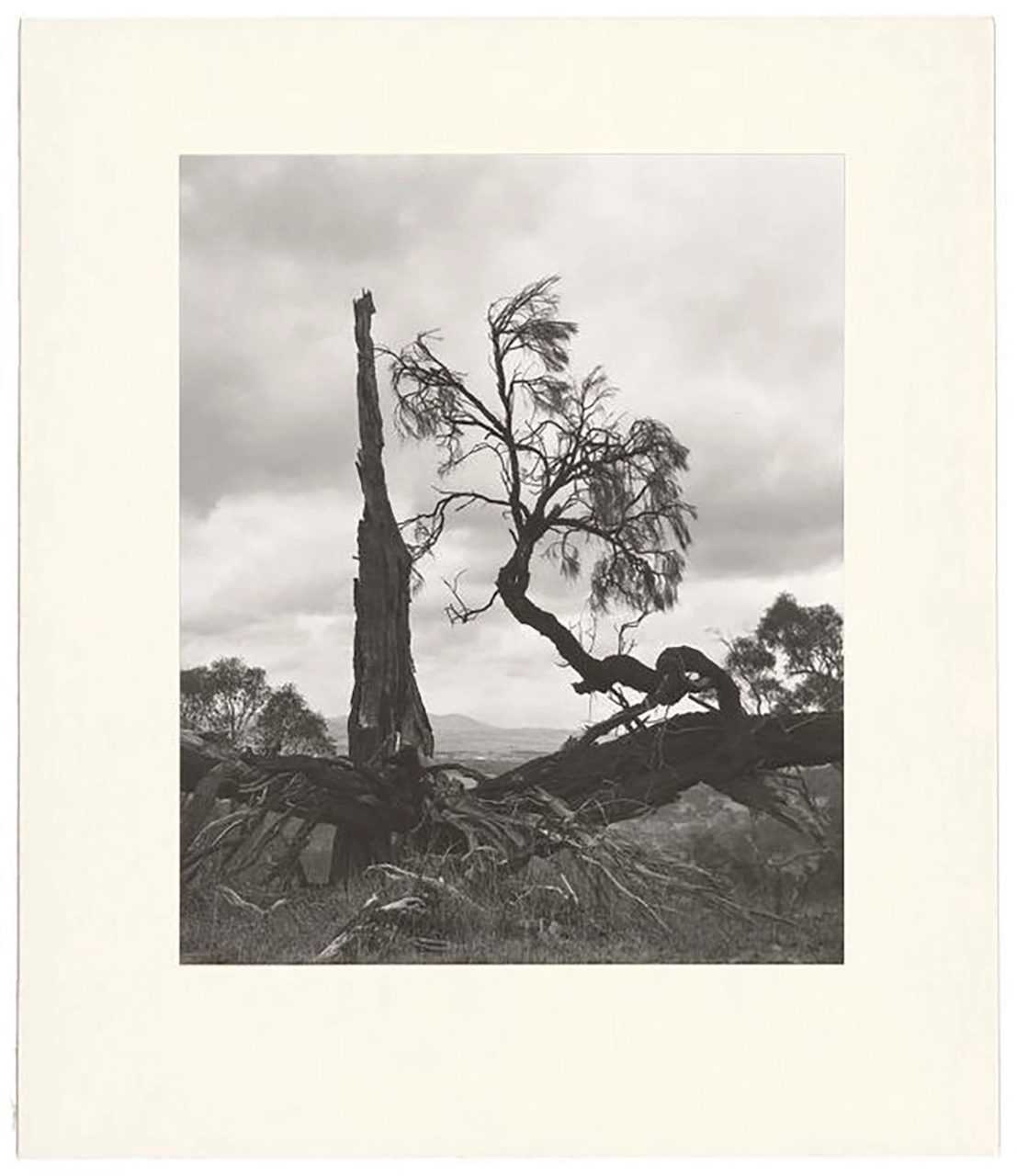

SC I'd originally wanted to write about a particular tree, possibly Ada, a Mountain Ash, but I couldn't get anywhere. And then I started to just think about the @sophtreeofday, which is an Instagram I have, and my attempts to kind of continue to keep some connection with trees and their stories, despite the fact that I was sort of trapped in Fitzroy. And so, I wrote first about the trees within the 5kms that I could see during lockdown. As I started working on that lots of different things came to me about the grief of that whole time. Wasn't just the pandemic for me - it was the bush fires, which sort of led into the pandemic and that loss of animal life. So, I decided that I didn't really wanna write a conventional essay. I just really wanted to allow that sense of fragmentation and memories, different memories and ideas and knowledge about things I knew about trees, allow them to come to write about them.

SC And then I got the idea of writing back into time and out of time because one of the things that continues to strike me really is that in this kind of era, the era of fire is built on the era of the great forests and trees laying down and becoming carbon. And this sense now that this is all being burnt and destroyed and exploited, there's such a relationship between deep time and the very particular time we found ourselves in when I was writing that essay and I had, when I was researching city of trees, come across this idea that trees tend to spiral when they're stressed, and they show particular growth marks. As the kind of pressure grew in Melbourne, there was a sense of people were becoming very reactive and emotional. And I had a sense that that was the last thing we needed, that we just needed to calm down and get through what was going on; allow ourselves to be in the moment rather than judging it, which is sort of what trees do. Trees stand there, weather comes, weather goes, the soil changes. They interact differently with what's going on. And I do feel that trees can communicate in some kind of emotional way, but they just are. And so, I, what did actually find that kind of as, as a coping strategy, very useful as well is not getting kind of as overwrought about how I feel bad, or this is not good. It just was where all the situation that was occurring that I felt phrase were kind of like an emotional role model for me in that well can imagine role model. Anyway, unlike Brian, I don't have that kind of historical and inherited relationship with trees. So, I was sort of, to some extent was finding myself, imagining what I believe the trees may or may not be feeling and how they might be coping.