In Relation – Spectres and Sentinels

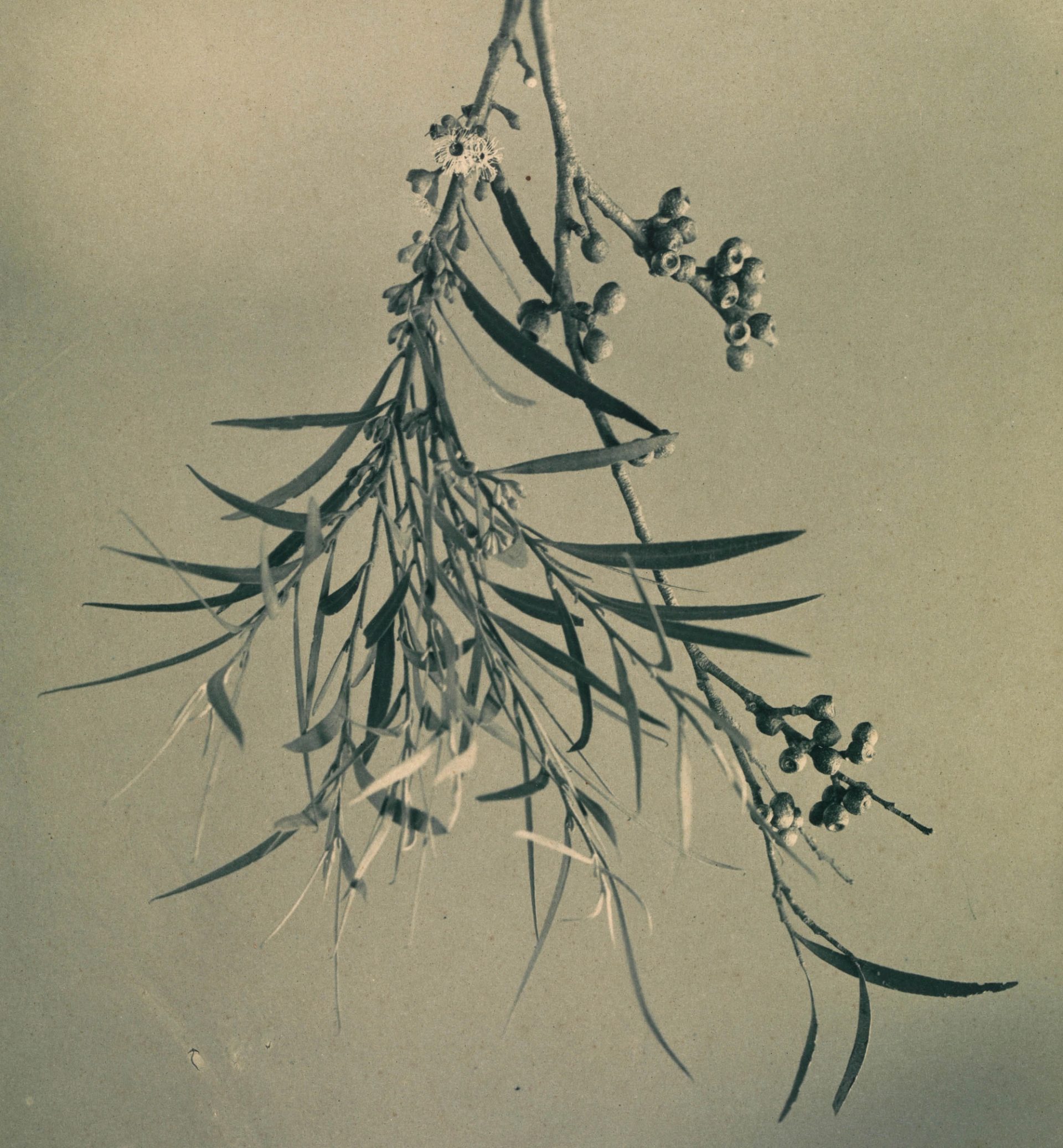

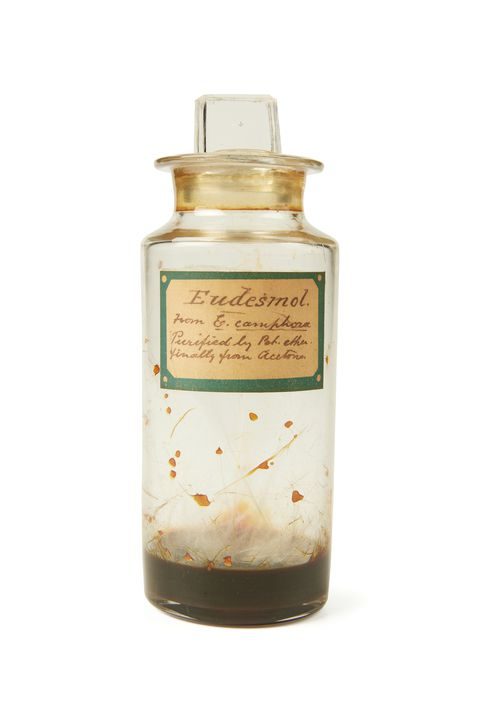

‘Spectres and Sentinels’ is the final episode of In Relation, a five part podcast series by Powerhouse inspired by eucalypts and the Powerhouse exhibition, Eucalyptusdom.

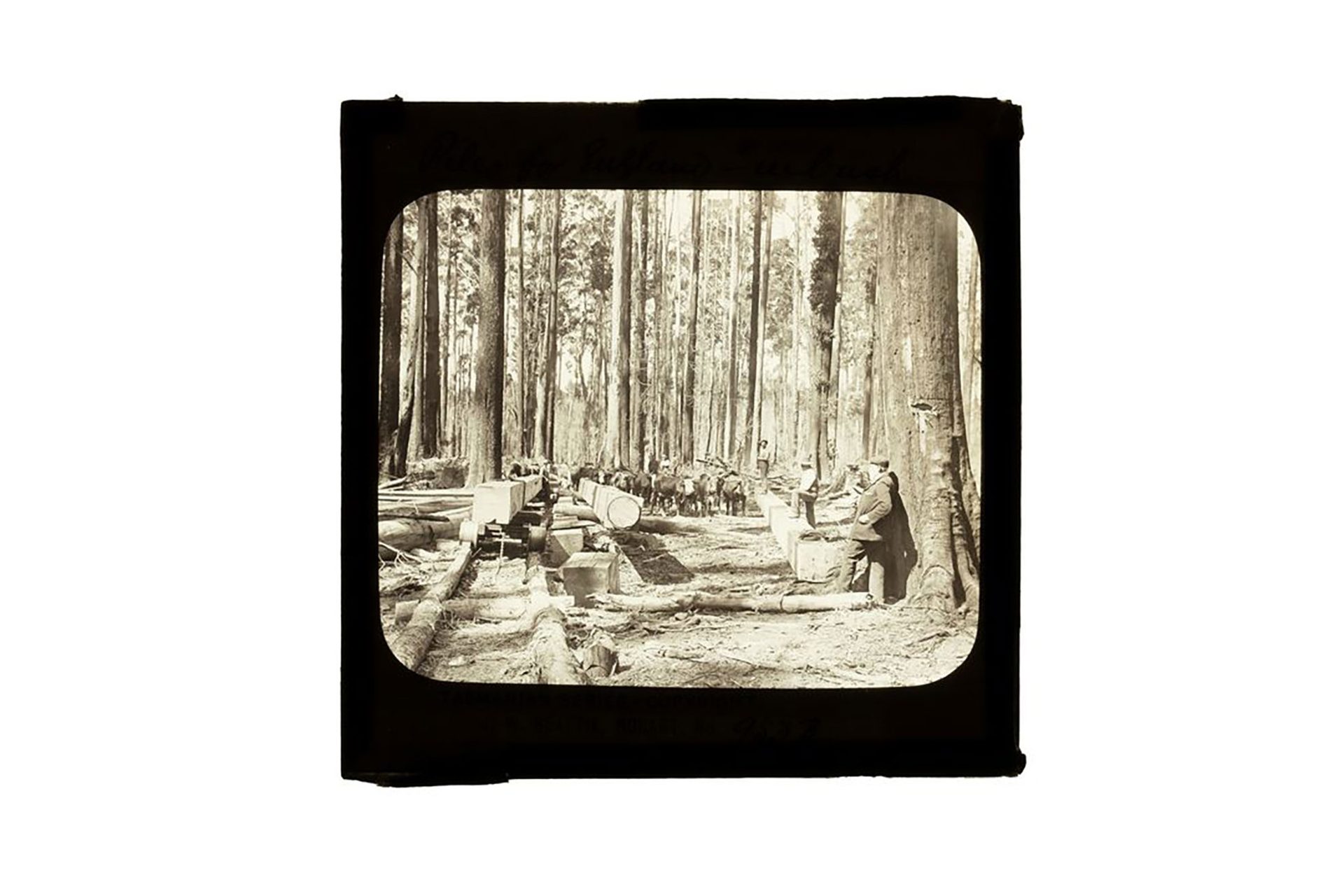

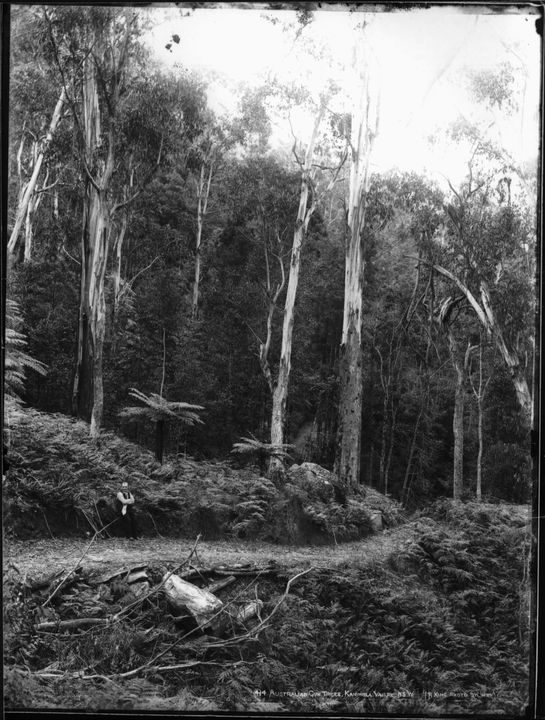

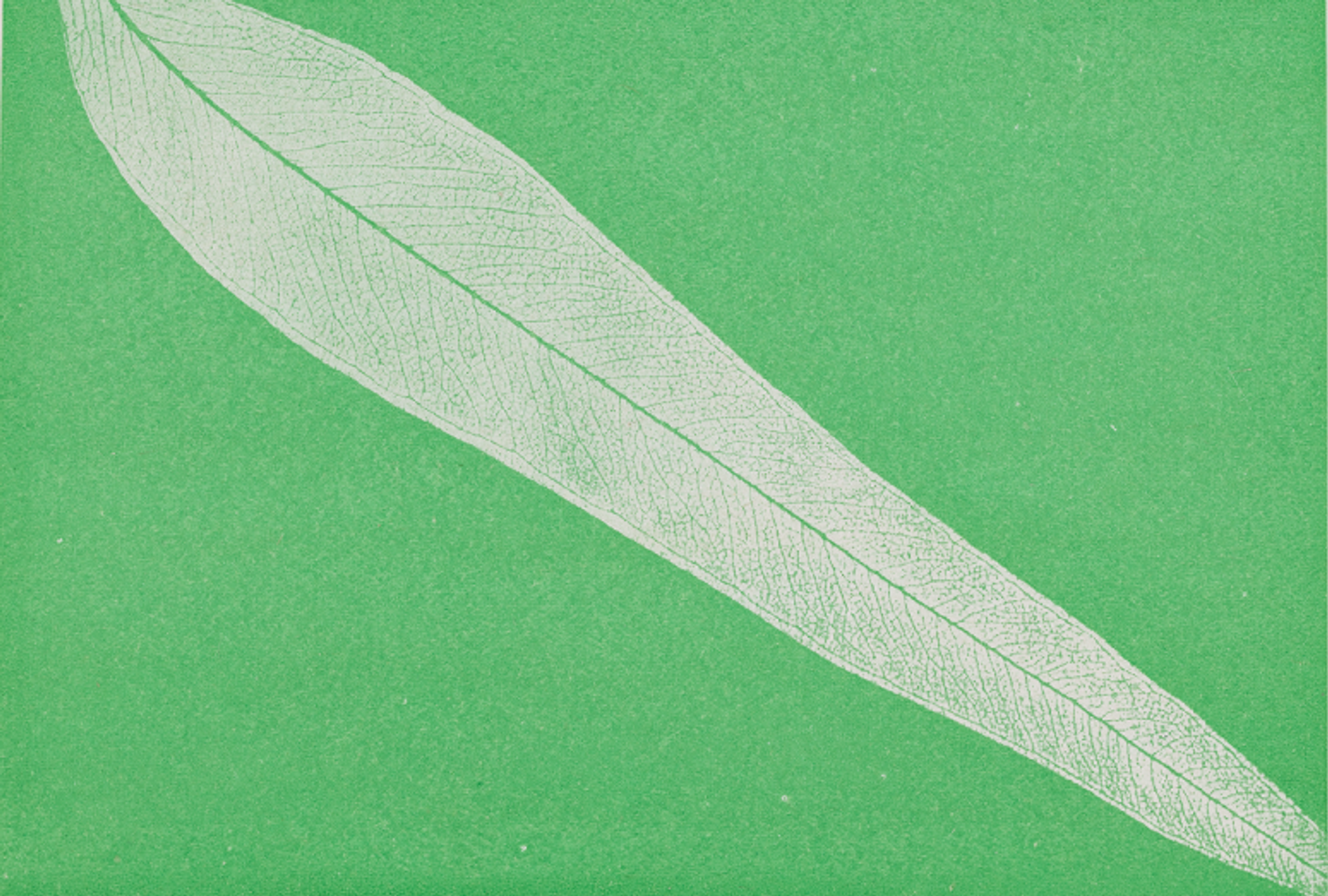

We discuss the eucalypt as sentinel and witness to contested, obscured and enduring histories in Australia. What can we learn from trees that have withstood and absorbed the past, and what can this teach us about our futures?

‘Some of the Country where the trees are, I grieve when I visit, and other places are struggling to regain themselves in a way. But if a tree is living, there's hope, it's still part of a network.’

Transcript

Agatha Gothe-Snape The Powerhouse honours the Traditional Custodians of the land on which our museums are situated. We respect their Elders, past and present and recognise their continuous connection to Country.

We respectfully advise First Nations audiences that Eucalyptusdom and this podcast, In Relation, address the museum's colonial collection practices and include objects and materials of and from Country. This episode also contains references to colonial violence and the removal of children.

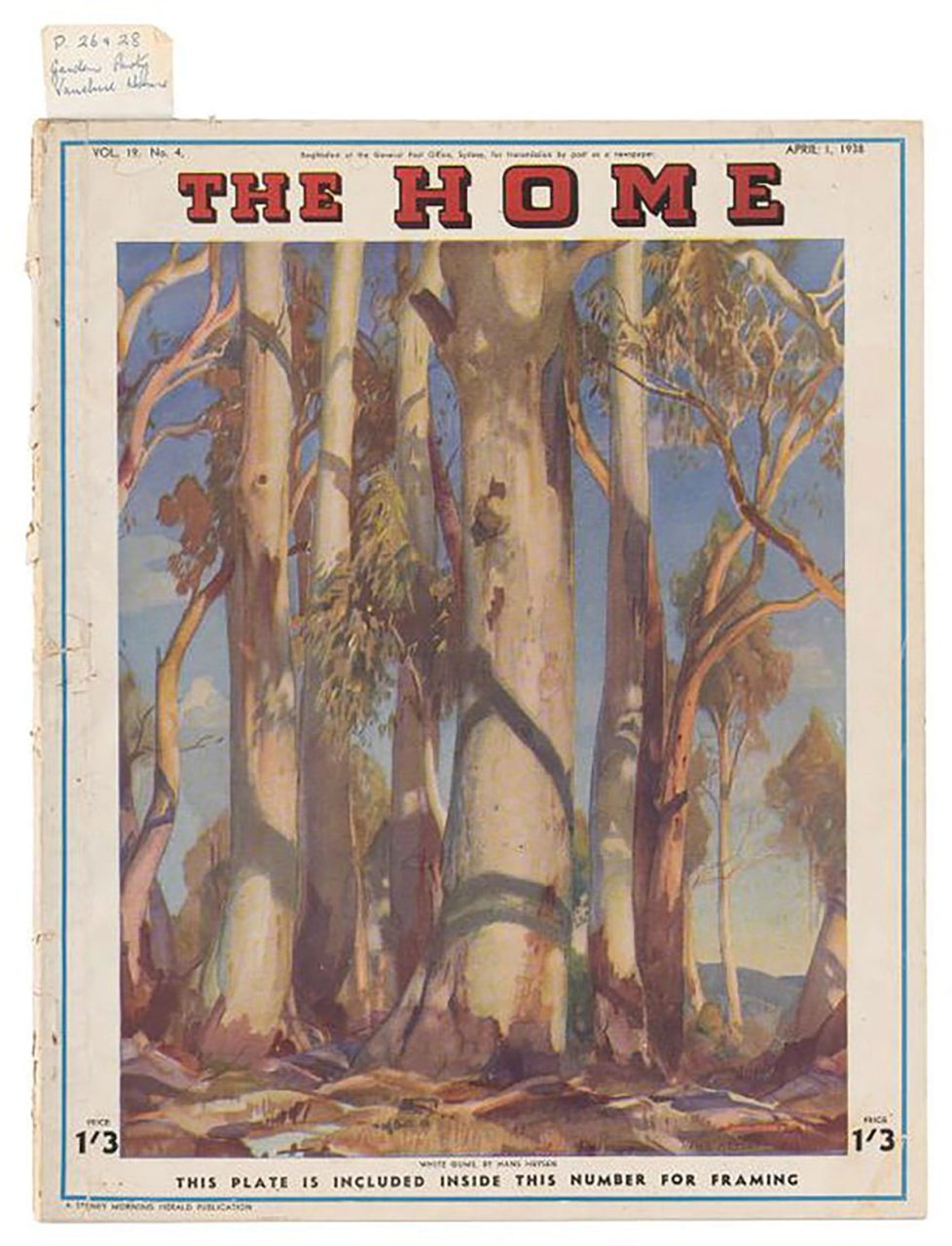

I'm Agatha Gothe-Snape, and I'm an artistic associate at the Powerhouse museum in Sydney, Australia. I co-curated the exhibition Eucalyptusdom alongside Nina Earl, Emily McDaniel, and Sarah Rees. This exhibition reckons with our cultural history and ever-changing relationship with the gum tree. It contains over 400 objects from the Powerhouse collection alongside 17 newly commissioned works.