JG Another huge influence has been Neil Perry.

KK Neil was a wonderful mentor — and after the first squeamish five weeks at Rockpool, I started feeling more relaxed. I was in the larder washing the garden salad and he said, ‘Kwongie, if you can prepare the garden salad at Rockpool perfectly, then you’re going to be all right.’

It was about choosing the most beautiful leaves. Then washing and preparing them mindfully, spinning them so there was no water. Then making the vinaigrette. ‘Kwongie, there’s a way to make a salad, adding the right amount of dressing so you don’t drown the leaves, so you don’t make them greasy, but so it’s tasty. Putting it on at the right moment so it’s not drenched by the time it reaches the customer.’ It was this beautiful, simple, Zen lesson.

JG God is in the detail.

KK I was ready to hear those lessons and I became obsessed. He was so inspiring. ‘Kwongie, do you know how lucky you are, coming from your Chinese heritage? Chinese food’s one of my most favourite cuisines. It’s so elegant, it’s complex. It’s sweet, it’s sour, salty. You should be very, very proud of where you’ve come from.’ And he said that in front of everyone. Well, that was a moment for me. He instilled me with confidence and made me feel proud of my heritage.

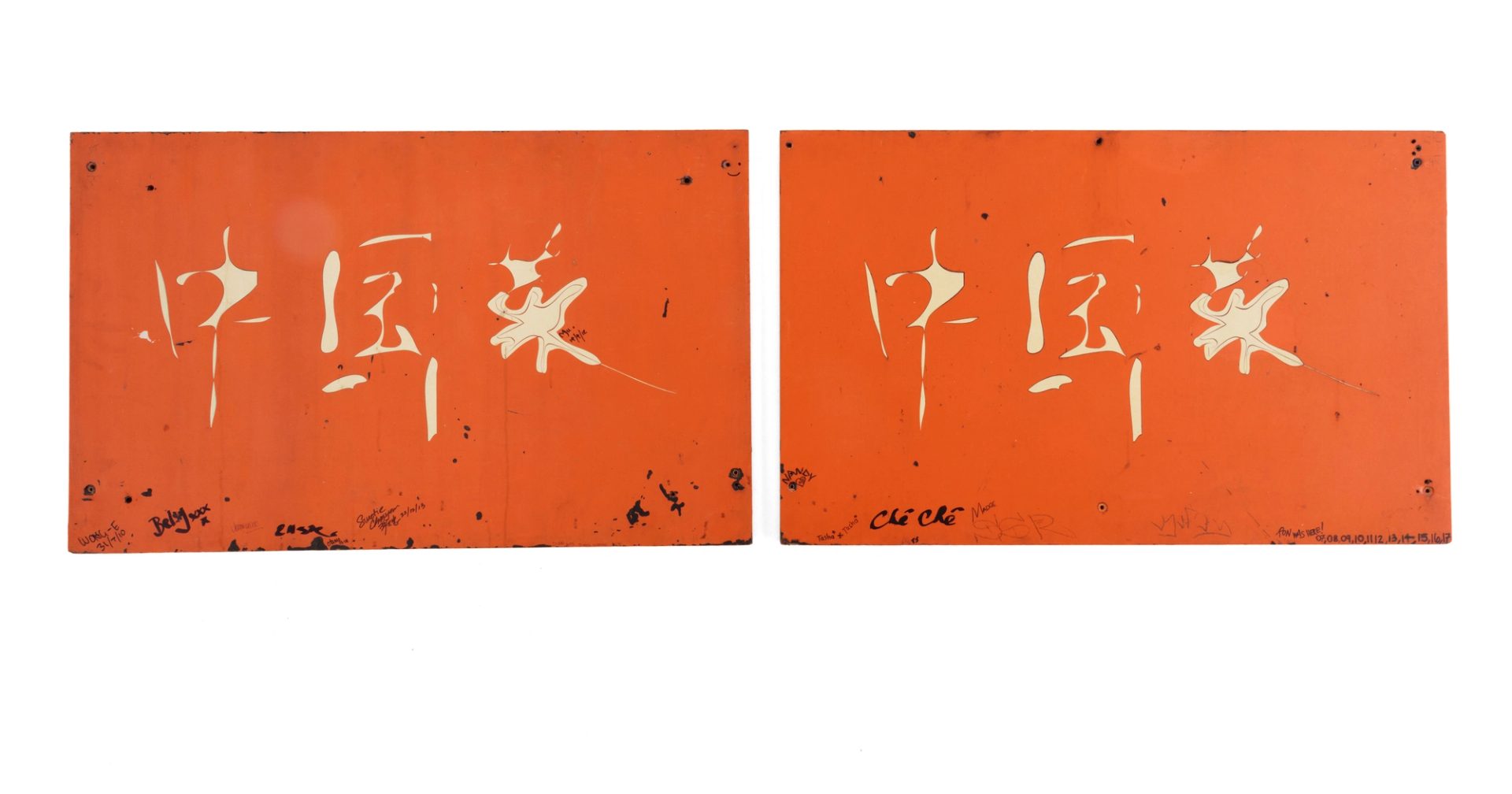

JG Billy Kwong opened in May 2000 — your first restaurant.

KK I wanted to open a quirky little hole in the wall, an arty eating house with an open kitchen where I could feed my family and friends and customers, and serve beautiful, fresh, simple, flavoursome Cantonese-style food. And the first night, I said to Mum, ‘I’ll be happy if we do 20 [customers].’ Well, I think we did 90. And it was a hit. Then in 2006, my father died. I was so sad, and that’s when I started opening myself up to community work, because it was very healing. I started getting into the fair-trade movement, community work, and I’ve never stopped, which kind of brings me to where I am today, I think.

JG Then you met another mentor, René Redzepi [then head chef at Noma, in Copenhagen], which was life-altering?

KK In 2010, René gave a keynote address at the Sydney Opera House. He started by saying, ‘Hey, Australian chefs, you know, I’ve just arrived here and I don’t see any kangaroo on the menu, or any of your Australian ingredients ... Guys, what’s happening?’

And then he spoke about his wonderful philosophy, how it’s an expression of time, place, history, culture, memory, emotion of the country. It’s very important to use the produce that’s grown in our own backyard. He used the word Indigenous and we were all just blown away.

Ben Shewry, of course, had already started using Indigenous produce, and the rest is history. It was a light bulb moment for me. And from the week after that, I started using native ingredients, which I would source through Mike and Gayle Quarmby of Outback Pride.

JG You then outgrew the Billy Kwong space in Surry Hills?

KK I moved to Potts Point in 2015, three times the size, dream restaurant, because the original Billy Kwong became so hard to work in from a practical point of view. Noma did their Sydney pop-up in January to March 2016. All the Noma staff would come in to eat at Billy Kwong, Potts Point. Having René, my mentor, so close and around the corner, his feedback gave me confidence and inspiration to stick to this path I was on. And then he invited me to the MAD Yale [Leadership Summit] week, where you could combine academia in the kitchen.

He taught me a whole other way of thinking about food and biodiversity and history. And that helped me go deeper into my practice. I thought, ‘Wow, what we’re doing at Billy Kwong, with our saltbush cakes, wallaby buns and stir-fried native greens, is actually a political statement.’ Being a chef, you can be really powerful, just by putting things on the plate.

JG And you found your First Nations mentors Aunty Beryl Van-Oploo and Clarence Slockee?

KK Of course, I wanted to learn from the Traditional Owners. Aunty Beryl had a Yaama Dhiyaan stall at Carriageworks Farmers Market on a Saturday, where I had my Billy Kwong stall. It was this instant connection.

She’s a local Kamilaroi Elder, an educator, a key community leader in the Redfern community and one of my most favourite people. Aunty Beryl and I went on to do masterclasses at Carriageworks regarding bush foods and how I started to integrate native edible plants into my Cantonese-style cooking. And I invited her to be the guest speaker at several of my Billy Kwong events. I also connected with Cudgenburra/ Bundjalung man Clarence Slockee, who is an award-winning horticulturalist and a bush food specialist.

JG Clarence grew produce specially for you?

KK When I opened Lucky Kwong at South Eveleigh, Clarence looked after the green space there and I asked him to plant a whole lot of edible native plants for me: old man saltbush, Warrigal greens, Geraldton wax, native bush mint, Karkalla, which is pigface. Every day we would harvest these native plants from the rooftop garden, which was 200 metres from the restaurant, and we were able to integrate beautiful, fresher-than-fresh ingredients into our dishes, telling the story of First Nations ingredients to our customers.

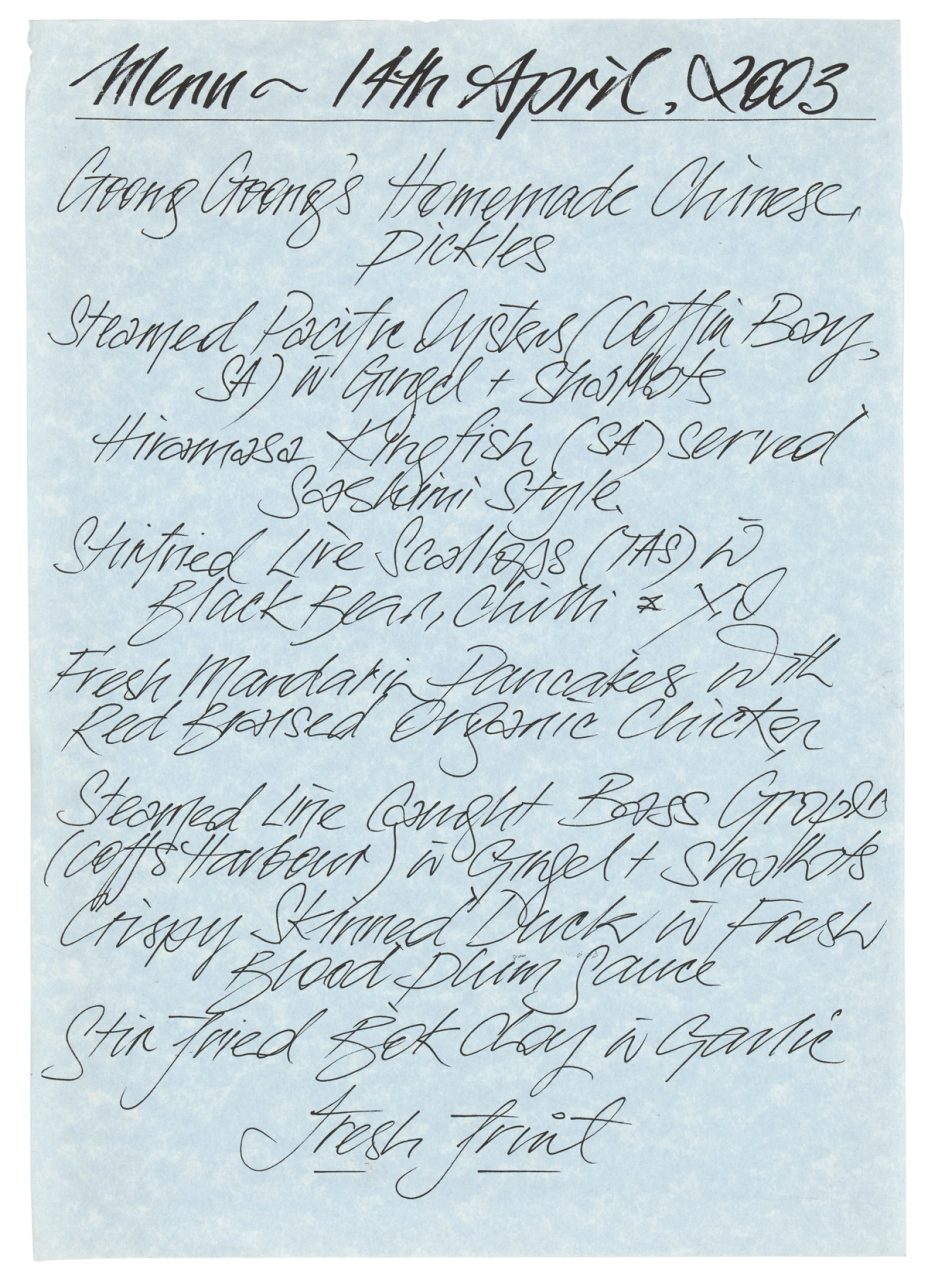

JG Describe the path that your duck dish took.

KK When I opened Billy Kwong in 2000, our most popular signature dish was the crispy-skinned duck with orange. And then sometimes seasonally I would use plums – European plums or blood plums. In 2010, when I made the discovery of Australian native edible plants, I became aware of the beautiful native Davidson’s plum, from the Byron Bay hinterland. It’s dark burgundy, really fleshy and delicious, and so sour, which I love. I thought, ‘Why am I using European plums in my signature dish when I now have access to Australian native plums?’

JG Do I recall that you would sometimes also use quandongs with that dish?

KK Australian native quandongs also worked perfectly. Sometimes I’d do the crispy-skinned duck with Davidson plums and quandongs, or crispy-skinned duck with tangelos and quandongs. We were not only offering our diners an authentic and meaningful version of traditional Australian and Cantonese food, but hopefully inspiring them to think about the First Nations story. So that to me was really powerful.