In his carvings, Evans lavishes close attention on sartorial details: the woman wears a bracelet, and the man a waistcoat, bow tie and watch chain; Artemis is adorned with a delicate crescent moon coronet on her forehead. The fabric of their clothes billows and drapes; fine lines mark out their folds and shadows. Evans’ figures are gestural, mid-movement. The gentleman extends his right hand towards the ground, almost as if he is giving way to someone. The woman holds her arms up in a graceful stance, as though she’s admiring something in the distance. Evans’ figures look to the side, not towards the viewer; they are each preoccupied by something unseen, just out of the frame.

The voyage Evans took to San Cristobal on the whaling barque Jane was an unhappy one, culminating in the disappearance of five men, and the prosecution of the ship’s captain for deliberately abandoning them. The facts of this incident were sharply contested in court, with eyewitnesses disagreeing on whether the men had deserted the Jane or been stranded to die at the hands of hostile locals.

What’s known is this: the Jane departed from Sydney in April of 1851 to the South Sea fishery with a crew of 30 men, including Evans as its cooper. By 16 October, the Jane had reached San Cristobal, where it stopped for wood and water. A week later, the Jane had the supplies it needed, and Captain Brazier gave the barque’s crew 24 hours of shore leave so that the men could wash their clothes in a local waterhole. Most of the crew had returned to the boat for dinner at 1.30pm, or a little later in the afternoon. By dusk, the captain sent a boat to shore for the remaining men, but only three returned. Whether by design or by accident, five of the Jane’s crew – John King, George Miller, Samuel Setter, Alexander Smith and Stephen Watts – were left overnight on the island.

The next day there was still no sign of the lost men and Captain Brazier ordered the Jane to lift its anchor and stand at sea. When challenged about why he wasn’t making a greater effort to find the men and asked how he could leave them ‘to the mercy of the islanders’, Brazier took a boat to shore with his second officer, navigator and four local boys. The boat was gone for two and a half hours. No witnesses could say whether it had actually landed or not. When Captain Brazier returned, George Russell – who’d been manning the ship’s wheel – overheard him say: ‘They will all be dead men in a month, and a good job too, the bastards.’ According to Russell’s testimony, the captain returned accompanied by ‘a strange islander whom the crew had not seen before’.

In Brazier’s trial, Russell testified that Captain Brazier ordered the Jane should set sail on a course for the south of the island, where the boat idled for three more days. He made no effort to find the missing men – neither lowering a boat nor dropping anchor for the entire three days – and swiftly replaced them with seven locals who joined the boat from their canoes. After this incident, Russell and two other crew members mutinied. They refused to continue whaling and were put into irons. The Jane didn’t touch land again until December, when it reached Port Jackson, at which point Captain Brazier had the three men thrown into Darlinghurst Gaol and committed to trial for conspiring to break up the voyage.

Russell’s fellow informants, James Hudson and Thomas Morgan, mostly agreed with Russell’s testimony, but Russell’s account was later called into question because he failed to disclose that he’d had a serious altercation with Captain Brazier a few months earlier, in which he had threatened legal proceedings against him, and was subsequently severely beaten and punished by being forced to make sennit – a plaited cord – for a fortnight on the ship’s deck.

The Jane’s chief officer Joseph Woods offered a differing account of the voyage. His memory was hazy, he claimed. He remembered the difficulty in coaxing the men back on board, and the captain saying, after the attempted rescue the following morning: ‘Those men will die of fever and ague, they are very foolish people so to leave the ship.’ He also claimed that a change of weather and a heavy current meant that it was too dangerous to attempt rescue again.

The second officer testified that the weather had been ‘dirty’ during the men’s shore leave, and that George Miller initially returned to the Jane at dinner time, before returning to shore by insisting that his clothes were still drying on the island, and then refusing to return to the ship. The second officer also testified that by the time the captain reached the island that evening, the men had vanished, and the coastal islanders reported they had gone to the mountains, where there were hostile tribes. He claimed the captain had offered the coastal islanders two axes for each of the men – objects which were highly valued – and extracted a promise from the chief to look for them, but who subsequently reported the men were beyond recovery, even when further rewards were offered.

The second officer testified that it was Russell and his fellow informants’ refusal to continue whaling that forced the Jane’s return to Sydney. The ship-keeper and navigator Charles Wentworth testified that the men had deliberately deserted and were prepared ‘to take up their abode in the island’. Alfred Evans corroborated this account, and the magistrate dismissed the charges. The five men left on San Cristobal were never found.

Somewhere on this calamitous voyage – either before or after the disappearance of the five men, and the subsequent mutiny of three more – Evans was etching his microscopically fine, controlled lines into sperm whales’ teeth.

The only other small glimpse into what life might have been like for Evans on the Jane comes from the best-known whaling scene in Tasmanian colonial art: a brutal skirmish called Offshore whaling with the Aladdin and Jane by William Duke. While the Jane operated mostly out of Sydney and Auckland, it also occasionally worked out of Hobart. In Duke’s canvas, the Jane floats serenely in the background, its blousy sails a pale wash over the Derwent. In the seething waves of the middle-ground, a flotilla of rowboats and harpooners rise and fall in the chop as they attack two sperm whales, one of whom is only represented by its disappearing tail. In the painting’s foreground, a whale’s mouth – open in agony, it seems, or exertion – reveals the sharp white rows of teeth. At the time Duke painted his canvas, whales were so plentiful in the Derwent that those who lived close to the river complained that the din of whale song at night kept them from sleeping.

Because sperm whales are unfathomably large, it’s natural to contemplate their size on a more human scale. The largest of the Odontoceti order (the toothed whales), sperm whales reach up to 24 metres in length, weigh up to 50 metric tons and have the largest brain of any creature on Earth. Put another way, they are roughly as long as a standard tennis court, or just shy of half an Olympic swimming pool. Primarily hunted for oil, spermaceti and blubber – material for candles, lighting oil, soap, varnish, paint and lubricant – sperm whales live throughout the warmer waters of the world’s deep oceans between 40 degrees south and 40 degrees north, fuelled by giant squid and fish. Travelling the world in pods of between 15 to 20 animals, they communicate by sonar clicks – known as coda – at the volume of a rifle shot, loud enough that nearby divers can feel the reverberation in their bodies. Over the centuries some sperm whales have learned to avoid whaling vessels and warn nearby pods to stay away.

Their monolithic heads are square, with a shallow trapdoor of a lower jaw counterbalancing their bulbous spermaceti organ. Around 24 pairs of teeth on their lower jaws – ranging between 13 and 20 centimetres in length – nestle into deep sockets on their toothless upper jaws. The largest teeth of a sperm whale on record – collected from a specimen caught between Argentina and Uruguay – weigh more than 1.8 kilograms apiece. Drawing on scenes he witnessed firsthand on Atlantic and Pacific whaling boats, Melville describes the stubborn extraction of a sperm whale’s tooth as being akin to an ox in the Michigan woods dragging out the stump of an old oak tree.

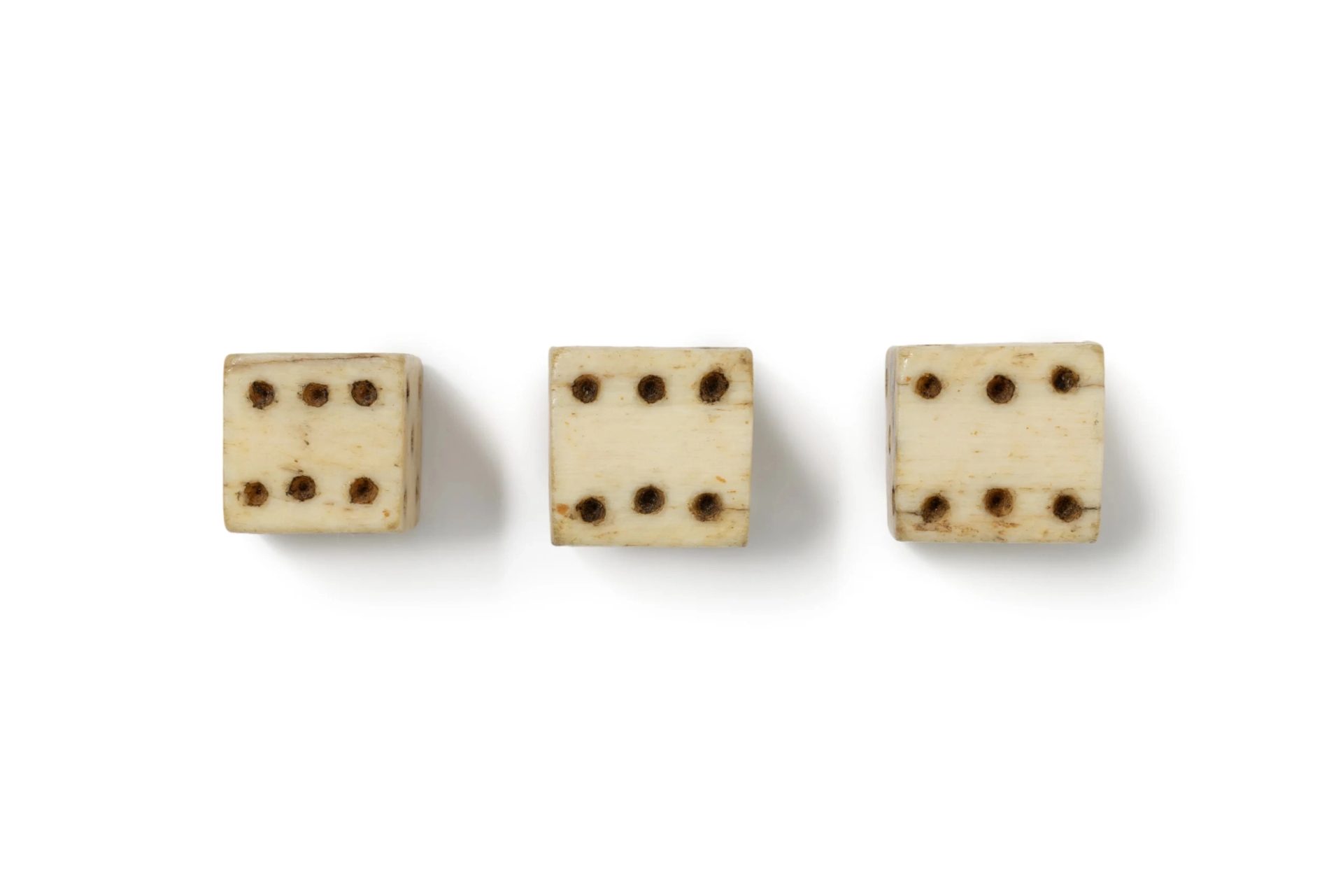

While sperm whales’ teeth were initially incidental to the hunt, they became prized by the whalers, who would trade tobacco or do additional chores to extract a tooth from the second mate for scrimshaw. Tooth in hand, the whaleman would work quickly, as the material could harden when exposed to air. Using a file, he would abrade the ridges of its surface, then polish it with dried shark skin or pumice, then cut lines with a sail needle, jack knife or other sharp point. Sometimes the strokes would be relatively artless and coarse; other times they would be fine as a filament, solid or stippled. Occasionally whalers would trace images from newspapers or other sources onto the tooth’s surface by pricking through the paper into the enamel: a ghostly transference. Rubbing the grooves with soot, oil, Indian ink or lampblack helped the image stand out in relief.

The process was painstaking and slow – but the men had nothing but time.