South Pole Dreams

New York Times bestselling author Leslie Jamison looks at the role of talismans in extreme situations, following the dreams and shadows of James Castrission and Justin Jones across the Antarctic. Commissioned by Powerhouse for the Writing Objects series.

South Pole Dreams

Trekking towards the bottom of the world, two men daydream about English breakfast tea, vegemite on toast, washed socks – utterly ordinary things turned extraordinary by distance. We daydream about extremity inside banality, and banality inside extremity. In 2011, James Castrission and Justin Jones – Cas and Jonesy, best mates – skied together to the South Pole. 90 South: ‘home to some of the most inhospitable beauty on the planet’, as Cas put it. The allure of an inhospitably beautiful place is not unlike the allure of an inhospitably beautiful woman: pulling you close and pushing you away at once.

Their South Pole trek was an expedition fuelled by daydreams in two senses: they were motivated by the dream of doing something that had never been done before – reaching the South Pole without assistance, and then making the return journey – and they were sustained by daydreams along the way, the dreams that occupied their long hours pulling sleds across the ice. They daydreamed about wedding speeches, one-night stands, bucks parties, elaborate desserts. Cold bottles of Singha on a hot beach. Keynotes delivered to crowded rooms. They lived on daydreams through a season of endless days: a Southern Hemisphere winter of night-less light.

The scale of their trip was pointedly extreme: they travelled 1130 kilometres from the geographical coast to the South Pole (and then turned around and came back again), through blistering winds and the vast, unrelenting white of the world’s emptiest continent. It took them 89 days, burning 9000 calories a day, temperatures hovering at -20°C, their faces darkening with frostbite. For them, their trek marked ‘the boundary of what was possible’.

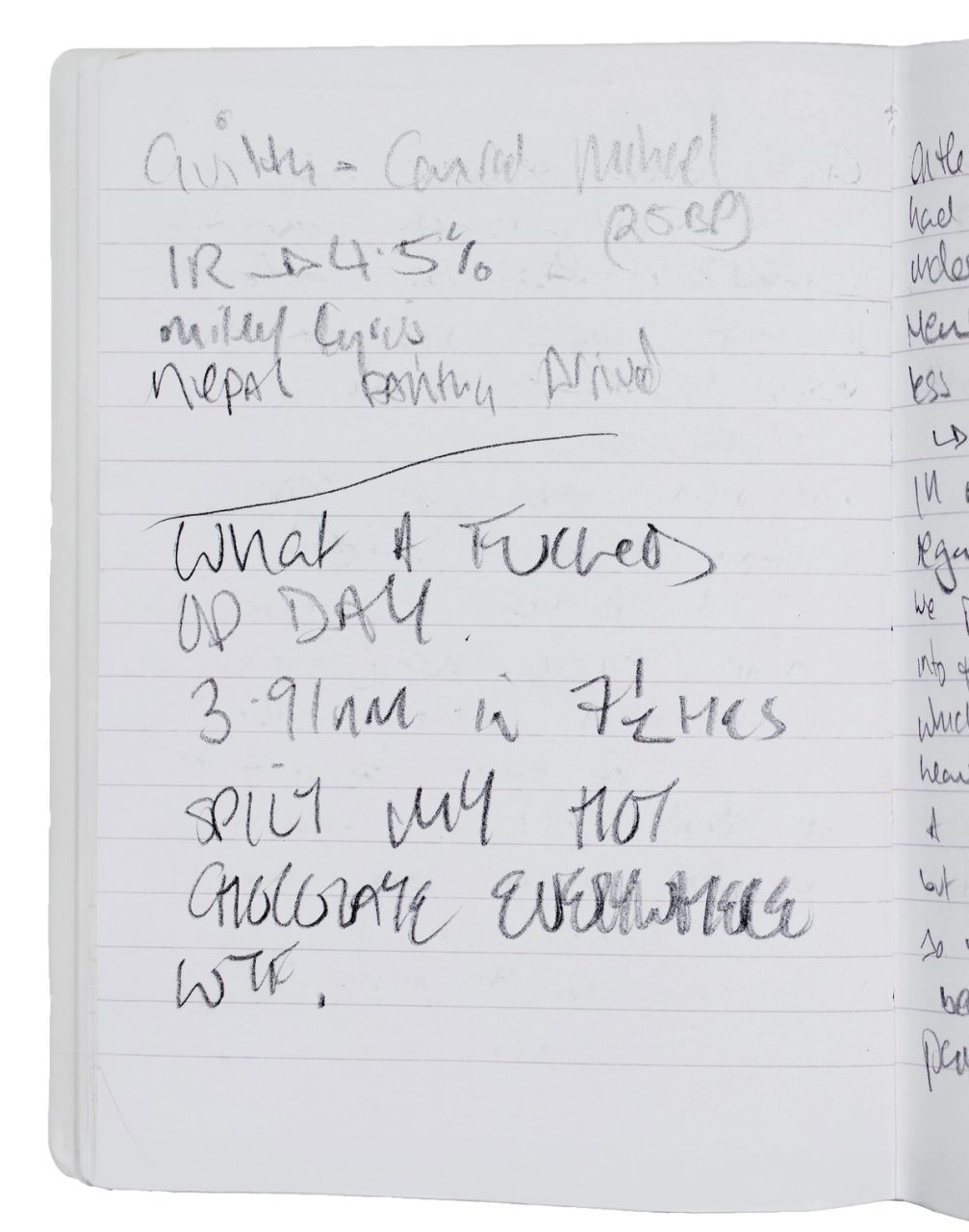

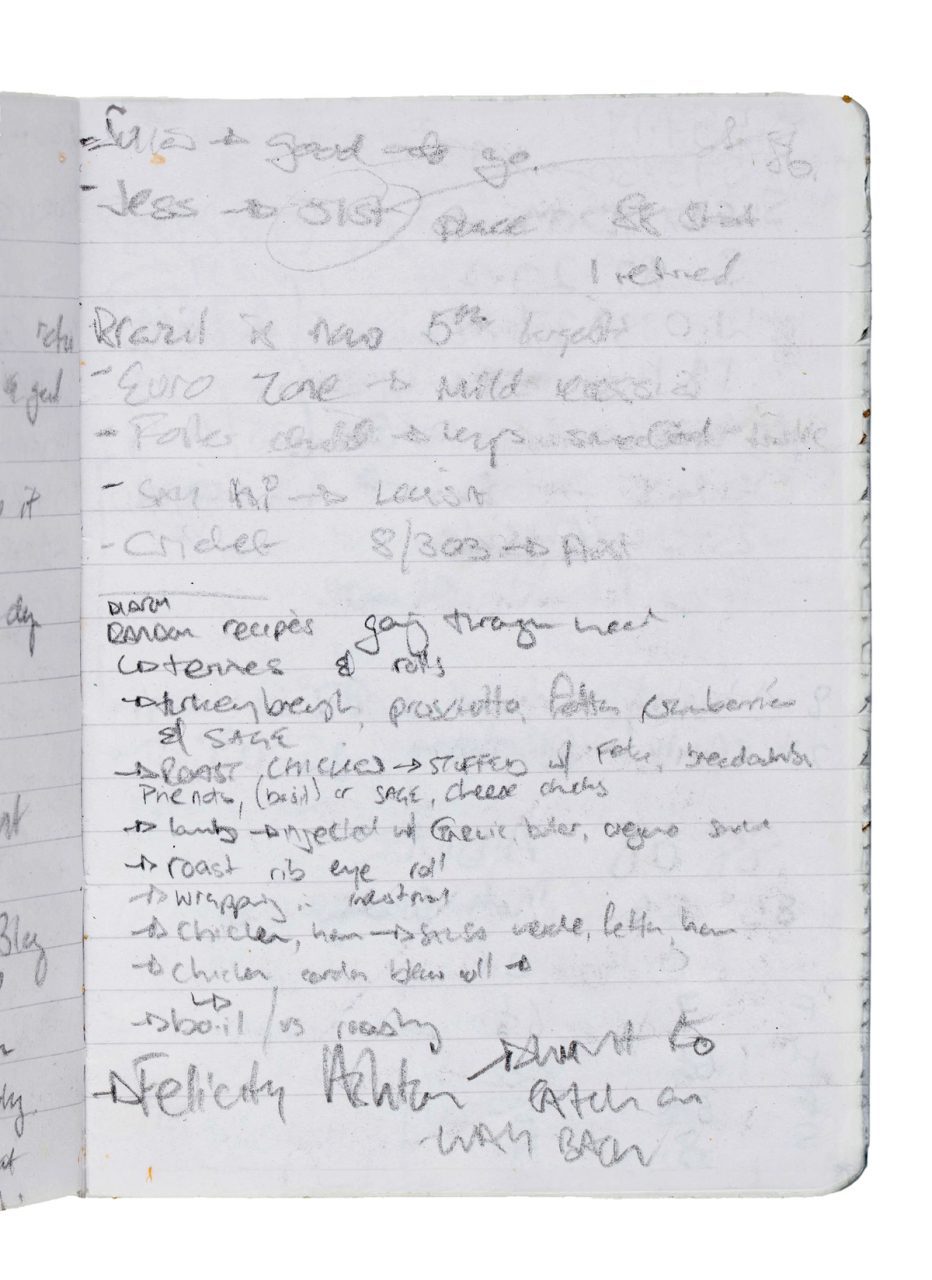

Back home, the pair led very different lives: Cas was getting married a month after they returned to Australia. Jonesy was still a bachelor. In his diary – writing in a cramped tent, with a shrinking pencil – Jonesy writes about the difference between their lives: ‘I rely on Cas too much – probably unfairly as he’s entering a new phase of his life. To tell the truth … I’m scared the depressed Justin will come back under the facade of the happy social Justin.’