Trading Stories

Shehan Karunatilaka, winner of the Booker Prize, has been commissioned by Powerhouse to write about objects in the Powerhouse Collection. In this work he shows how the business world embraces storytelling as much as novelists do.

Trading Stories

Pick a few objects and write about them, they said. Seemed simple enough. Was anything but. When browsing a museum as extensive and as eccentric as the Powerhouse Collection, shortlisting a handful from a half million is a very particular challenge. You begin by clicking anything that catches your eye (which is most of everything), curate your own warehouse of the strange and the enchanting, and then get lost in labyrinths of story, history and curiosity.

Then, after a while, a few objects begin speaking to you. And you listen as carefully as you can and go in for a closer look. The curiosities are whispering across time and sharing variations on a familiar tale, one that has recently colonised your thoughts.

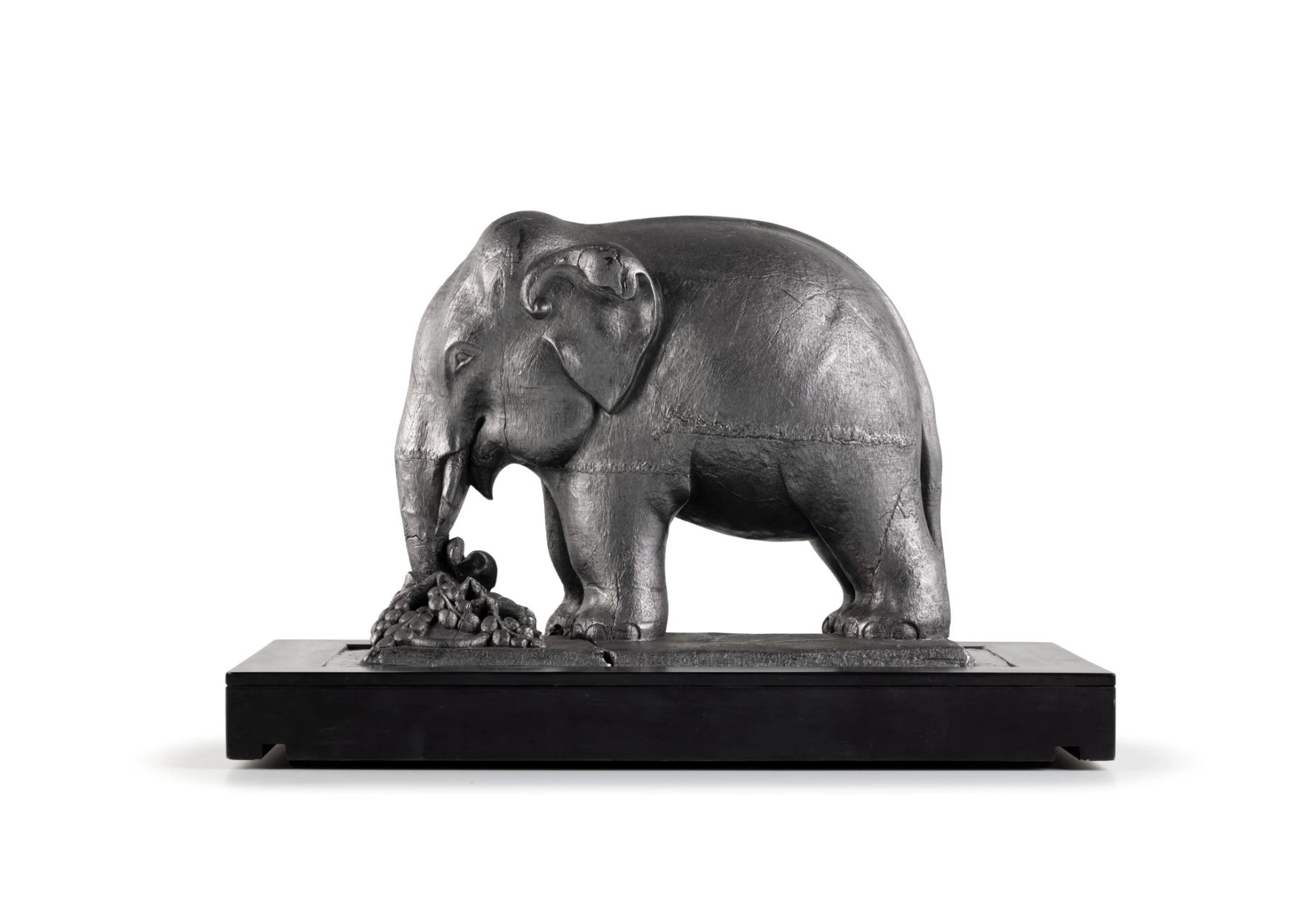

I ended up with four objects, each from a different century, made in a different country. A coin, an elephant, a calculator, some sunglasses. One made of gold, the others of metal, graphite and plastic. These treasures share neither design nor function, neither texture nor colour, but to me, they tell similar stories, articulating ideas on commerce and invention, tales I am only just beginning to grasp.

Each would’ve been a minor innovation of its day, reflecting an economic paradigm shift of its time: the minting of currency, the automating of finance, the wearing of technology. Two of the objects are innovations of science, two are works of artistry. Each reflect the changing face of commerce over the centuries and prompt reflections on business, fiction, objects and obsolescence.

Let’s begin with Object No. 2009/21/1-77. A gold 1 Mohur coin from the British East India Company, minted in Calcutta or Murshidabad in 1774 in the name of Shah Alam II, who signed over tax collecting rights of Bengal, Bihar and Orissa to the East India Company nine years earlier, subcontracting the state’s power to a marauding corporation. The coin’s cursive inscription, curved symbols and dazzling sheen remind me of the Sri Lankan , a traditional pendant made for young children to ward off the evil eye.