The Universal Machine: Uncovering Ada’s Legacy

Toby Walsh, a global authority on AI, has been commissioned by Powerhouse Museum to write about objects in the Powerhouse Collection. In this work he uncovers the legacy of Ada Lovelace, the world's first computer programmer.

THE UNIVERSAL MACHINE: UNCOVERING ADA’S LEGACY

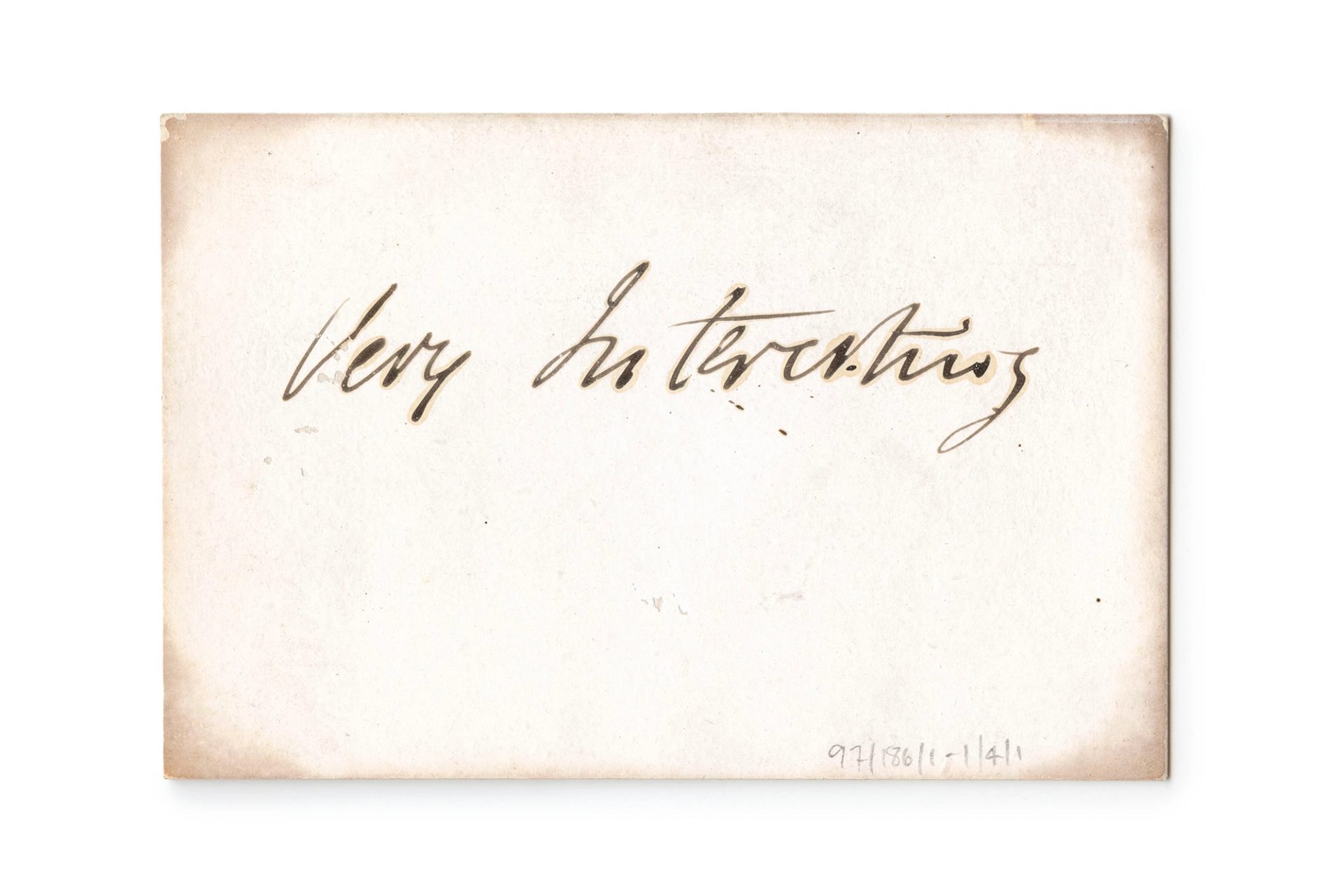

The visiting card has just two handwritten words on it: ‘Very Interesting’.

I can’t help myself from speculating what Ada’s marvellous mind found so very interesting. And whether it was about the future we are now inhabiting. After all, we live – to adapt that famous but apocryphal Chinese curse – in very interesting times.

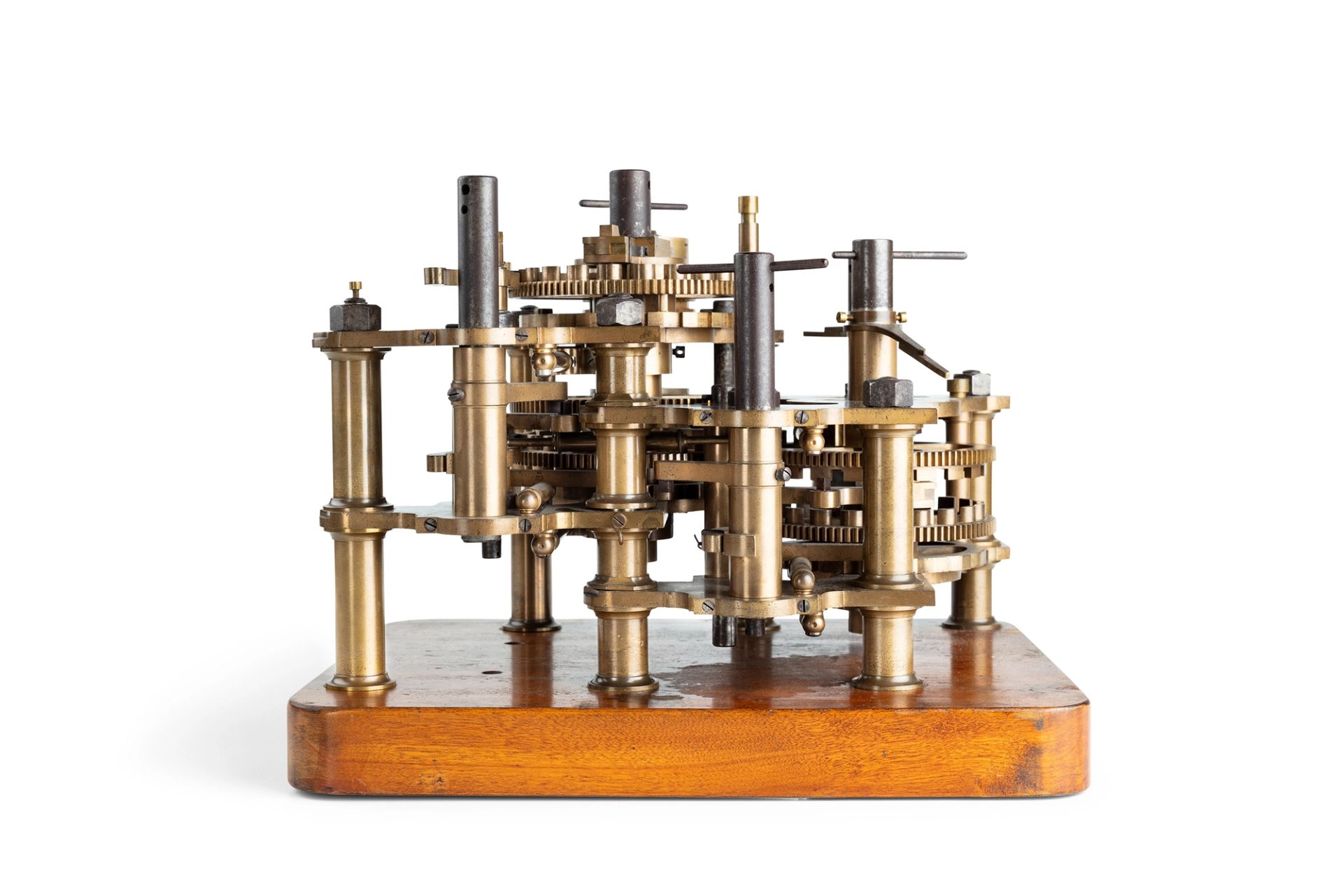

Is AI taking us to a digital dystopia? Or to a virtual nirvana? It’s hard to tell. But here, in the Powerhouse Collection, I uncover a trail of artefacts that lead from Ada to that artificially intelligent future.

My journey starts with Ada’s visiting card.

Abandoned early on by her famous father, the poet Lord Byron, she was, by all accounts, a gifted and, as was necessary for women at that time, a partly self-taught mathematician. Charles Babbage, to whom she had sent the card, admiringly called her an ‘Enchantress of Number’. Unsurprisingly given her father, she also brought a fine appreciation of the arts to her scientific studies.

Ada’s visiting card came in an envelope. I open Google Street View and type the address on the envelope: 1 Dorset Street, Manchester Square. It is an elegant street in Marylebone, London. Unlike the fine Georgian properties either side, number one is now a modern six-storey apartment block. Perhaps a bomb dropped here in the Blitz? I zoom in. I spot a round green plaque on the wall of the building. It is a plaque put up by the . And it bears the engraving: ‘Charles Babbage (1791–1871). Mathematician and pioneer of the modern computer’.