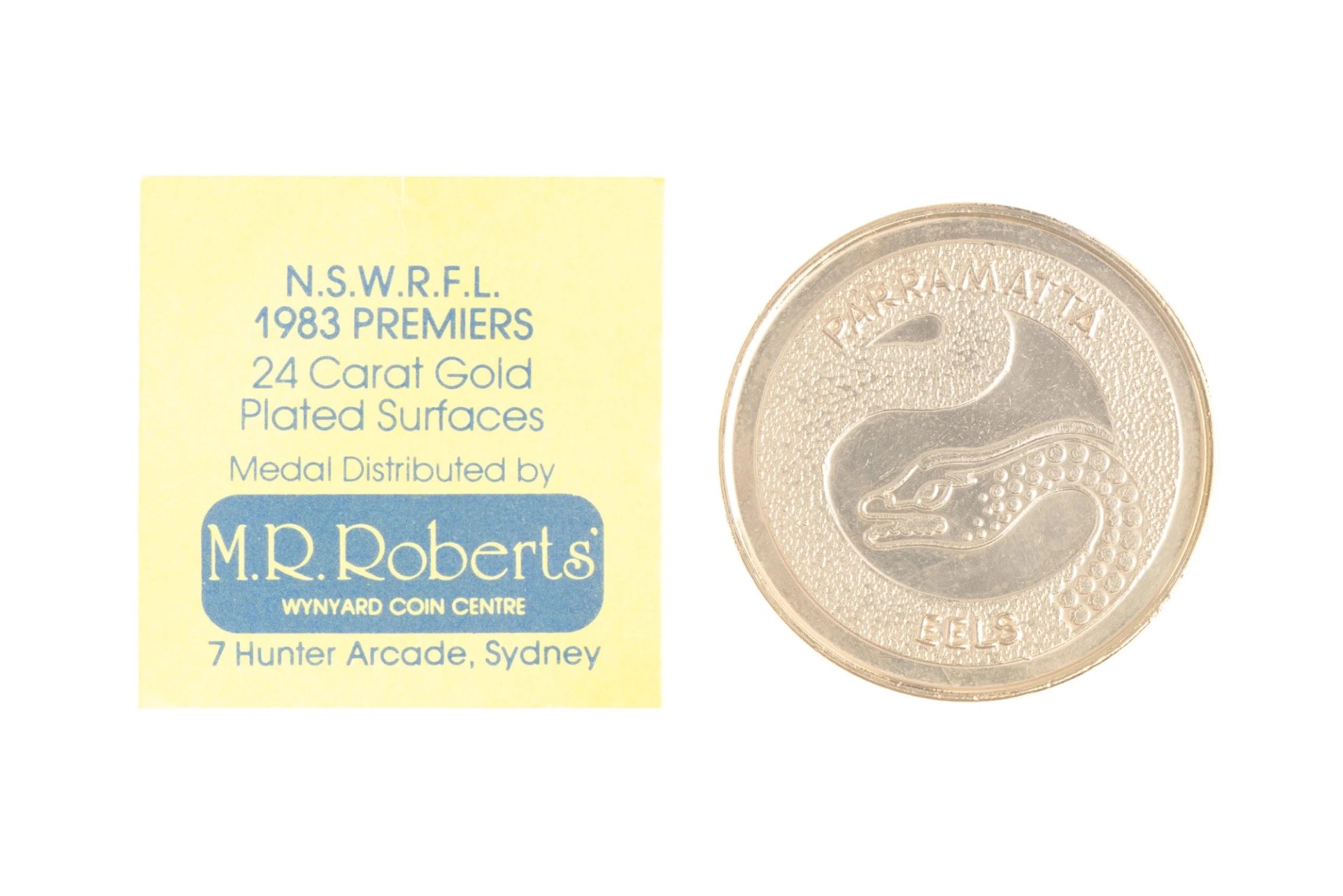

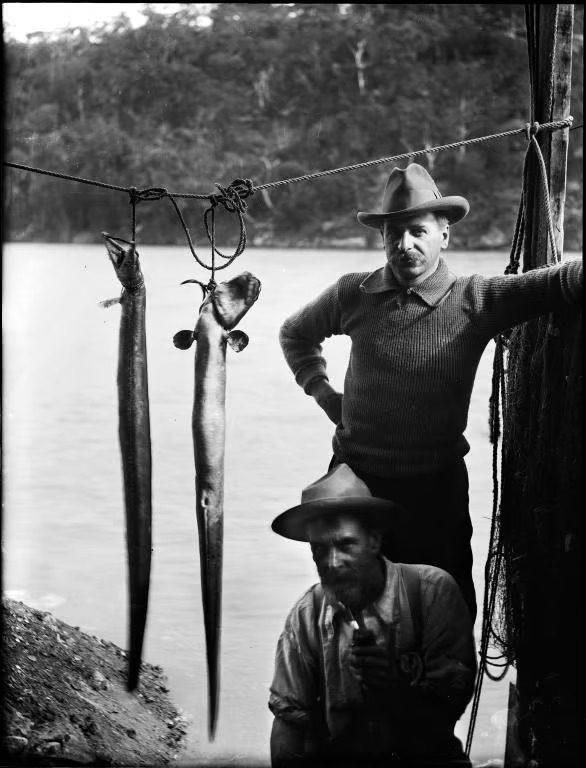

LTL In the Powerhouse Collection, you'll find a 19th century photograph of local fishermen with their catch of eel, back when the species was more plentiful. For a contemporary chef like Nik, it's important to preserve and maximise every part, as he does with Smoketrap Eels.

NH So, it's really a two-week process from once they first get in the net to sort of being on the plate. We don't waste anything and we kind of look for byproduct on byproduct. Originally, we even found little pockets of jelly that fall into the tail when you first smoked them that we were like, I wonder if you can get that out and try and sell that, because it tastes amazing, it's like this natural gelatine stock that comes out really smoky. The guys at Fish Butchery made a liver parfait with it for us once. Hearts are really iron-y and really not delicious, if I'm honest. People have used the skin to dry out for crackers. We've always been on this path to use every part of the eel as much as we can.

LTL There are other ways to source eels, too.

JN Depending on the eels that you buy, some eels have already been prepared for culinary use. A couple of eels I bought in Chinatown that literally came straight out of a tank and the attendant there dispatched it quite efficiently and then put it in a bag and handed it over the counter.

ED Eel is popular also in Tuscany, and if you go to the supermarket, if you want to buy an eel, you have to buy it live. They actually just pop it in a plastic bag for you and then like, you're going around in your shopping cart and your bag’s like, writhing around because they sell it to you live and you have to take it home and fillet it by yourself.

NH It's like a five- or six-hour process to do it all and yeah, it's not pretty — covered in slime and eel guts. But like I say, as long as they're like dead when you get them, that's cool. If they're alive, different story. After my experiences, I don't really mess with live eels.

ED I haven't yet dealt with my own live eel, partly because of their sustainability status. I'll eat it when it's served to me, because that would be an even bigger waste not to eat it. I haven't gone out to cook with it, even though where I live in Tuscany there is a real delicacy for eel there. But in Pisa, for example, and Livorno, about 30 minutes' drive from where I live, there's a traditional dish that uses newborn eels. So, they're very, very tiny. They're called ‘ce'e’, which is the local word for ‘cieche’. It means ‘blind’ because they don't even have their eyes open yet. They're like tiny, tiny newborn eels and they get fished as they are migrating from the sea into the rivers. So, in Pisa, they're making their way to the Arno River and just at the mouth of the river they get scooped up. They're protected now, so there's no fishing of cieche allowed anymore, but it was a delicacy. You would just be able to fish them yourself. You go there, you scoop them out, take them home, you cook them with garlic and sage and breadcrumbs and parmesan, and you eat that over polenta or with pasta. And in Livorno they would kind of cook them the same way but instead of the breadcrumbs, they would use tomato puree and eat it with toasted bread.

Glimpses: Smoke House (1979), Tasmanian Archives Smoked eels have a firm flesh and a delicate flavour. And once you're over the initial squeamishness, you wonder why you never tried them before.

NH We had these grand visions of making eel grey tea. We tried to play around with that, but there are just some things in life you realise no matter how much effort you put in, it's not really delicious. We've made eel soup but I think drinking it as a cup of tea instead of Earl Grey wasn't really a big vibe. The best things we found out of it is smoked eel vinegar. So, we take that katsuobushi dried eel and we soak it in half red rice vinegar and some sushi vinegar and a little bit of water so that as it hydrates, it just hydrates into it really gently. Soak it for six months and then cold filter it out and bottle it.