Honey

Culinary archive podcast Season 2

Join food journalist Lee Tran Lam to explore Australia’s foodways. Leading Australian food producers, creatives and innovators reveal the complex stories behind ingredients found in contemporary kitchens across Australia – Milk, Eel, Honey, Mushrooms, Wine and Seaweed.

Honey

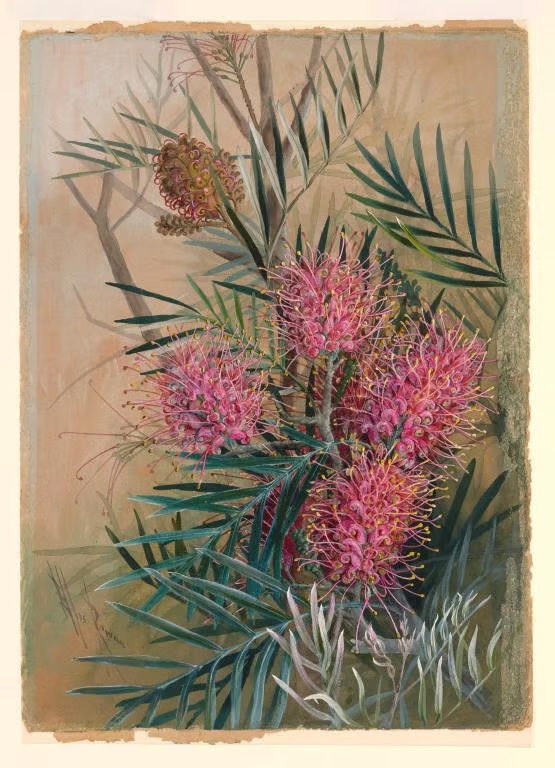

Australia is home to one of the world’s oldest honey cultures. For thousands of years, Indigenous people have harvested honey from sugarbag bees and honey ants which inspired kids TV and Japanese comic books. Australia’s native sweeteners probably predate the honey found in Egyptian tombs, which still proved edible 3000 years after it was buried. Contemporary Australians have found multiple uses for honey, whether in our food, on our skin or in our hair.

‘For centuries, beekeepers kept beehives on platforms in those trees to keep them away from bears. Look at the bark and you can literally see the scars from bear claws as they're trying to climb these trees.’

Transcript

Lee Tran Lam Powerhouse acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the ancestral homelands upon which our museums are situated. We pay respects to Elders, past and present, and recognise their continuous connection to Country. This episode was recorded on Gadigal, Yawuru and Wurundjeri Woi Wurrung Country.

My name is Lee Tran Lam and you're listening to season two of the Culinary Archive Podcast, a series from Powerhouse Museum.

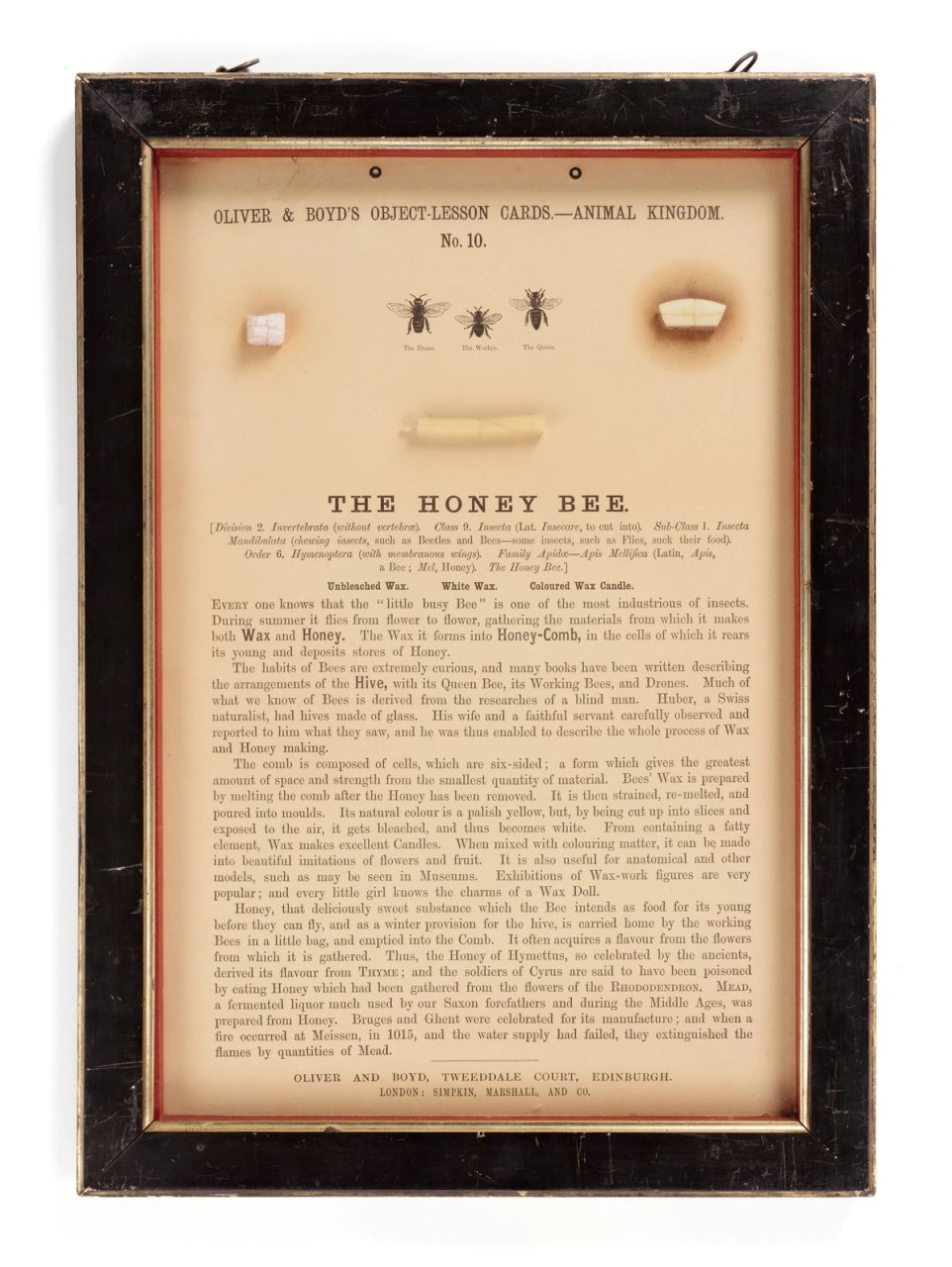

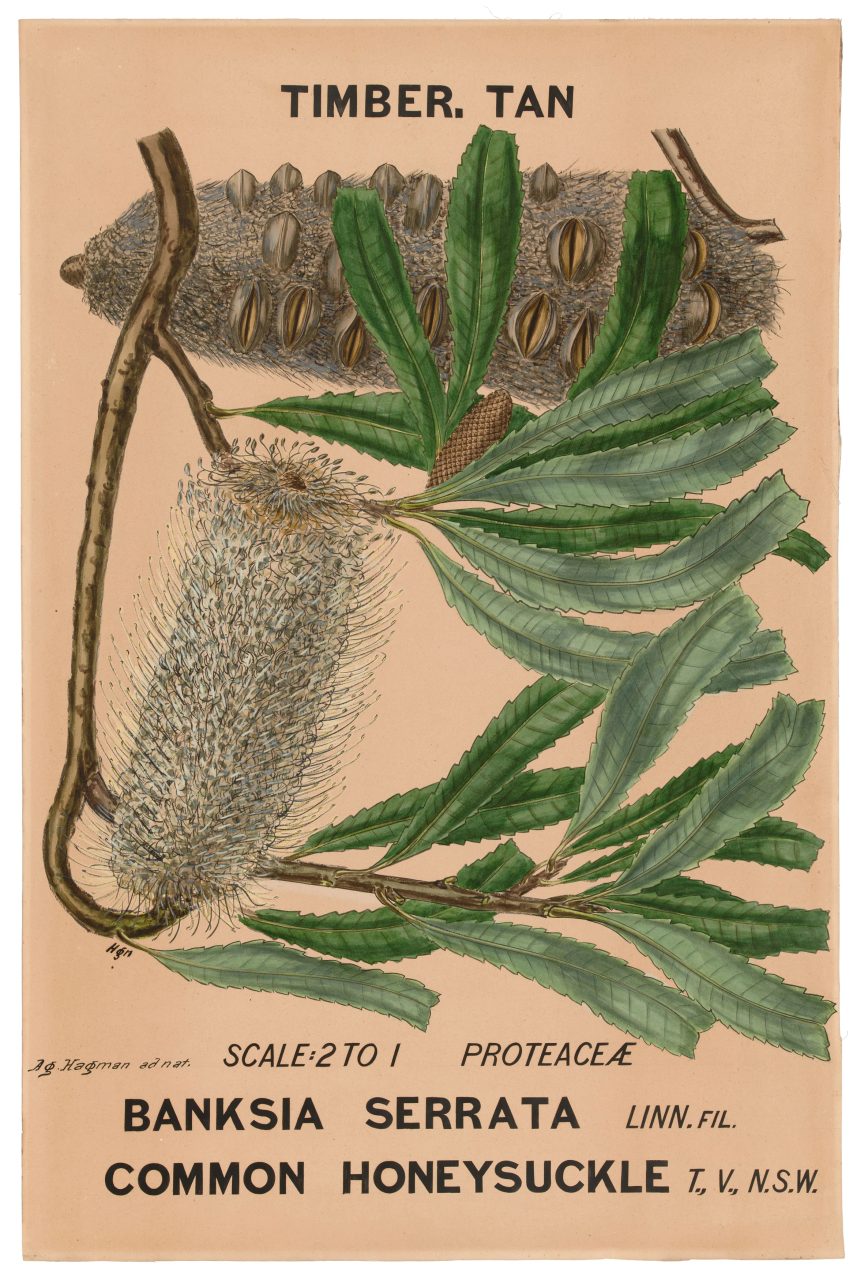

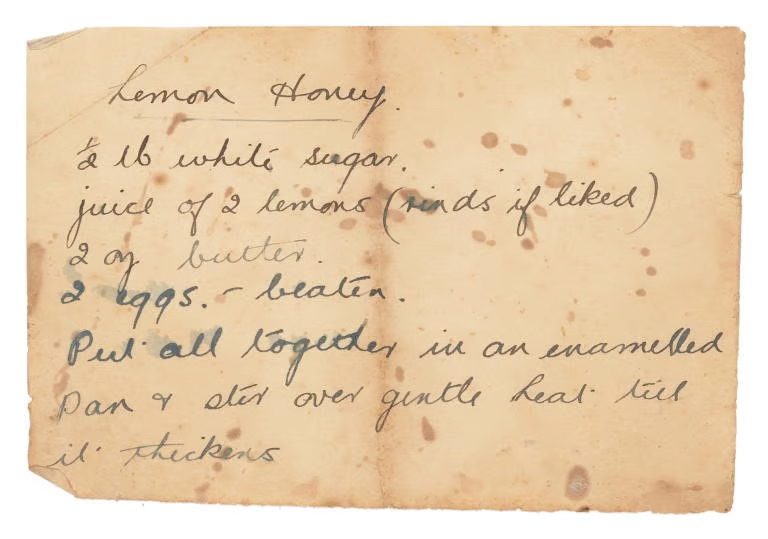

Located in Sydney, Powerhouse is the largest museum group in Australia. It sits at the intersection of the arts, design, science and technology with over half a million objects in its collection including a from the 1880s; a handwritten ; and The collection charts our evolving connection to food.