Language of the heart

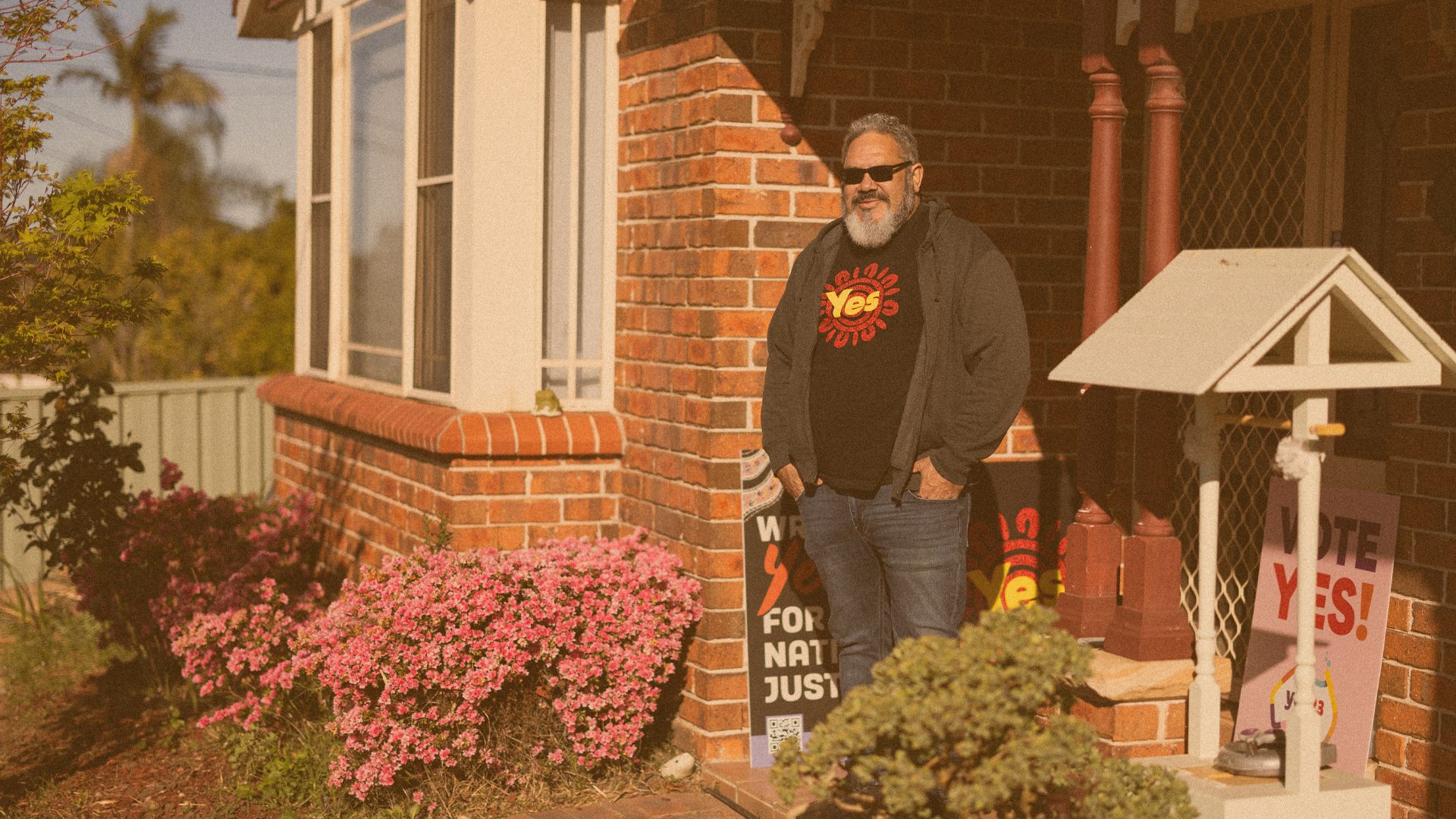

Speaking Tamil and connecting with the South Asian community in Sydney’s Greater West is central to the faith practice of pastor Jerulin Jones Sparks.

I suspect few people are as deeply aware of the threads between their present and past as my friend and pastor Jerulin Jones Sparks. She can’t talk about her ambition without talking about her father’s ambition, which saw him move to Merrylands in Sydney’s western suburbs from Chennai, India, without a single friend or family member on this continent.

Jerulin hasn’t lost her heart language, Tamil, and has gratitude for her mother, who banned English from their home.

We are in her office at the church we both attend, St. James Croydon, where she is an Assistant Minister. She tells me that most of the threads of her life weave together through the house church her family joined when she was a child.

Jerulin takes me back to when she was four. ‘One day, my mum and I were in Parramatta Westfield,’ she says. ‘I was running around more than I should have been, and Mum was calling after me in Tamil. This lovely man, Prabhakhar, recognised the language, came and said “hi”, and invited us to Bible study.’

I was allowed to sit and listen. It felt like a place of belonging.

On Saturday nights, between 20 and 40 people would gather at the house church in an apartment in Merrylands. ‘Everyone brought folding chairs. Lots of kids running around, lots of food, lots of South Indians.’ Jerulin remembers it as less of a traditional Bible study, more like a space for asking questions, for speaking one sentence in English and the next in Tamil, and to hang around for hours and have dinner. Importantly, it was a place in childhood where she wasn’t cordoned off to the side. ‘I was allowed to sit and listen. It felt like a place of belonging,’ she says.