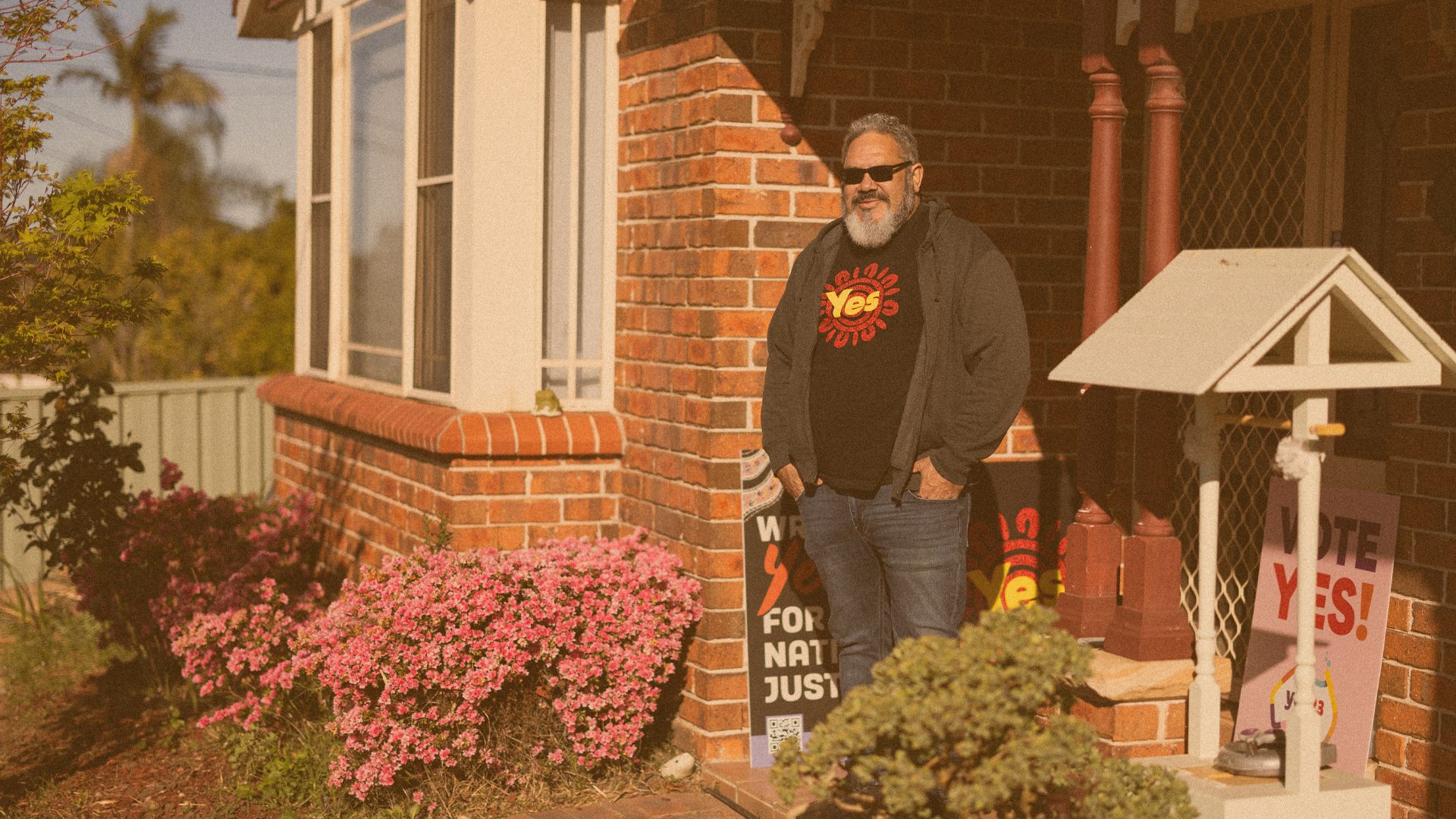

Parramatta Profiles: An introduction

An introduction by project editor Ellen O'Brien to 12 conversations with locals across Parramatta communities. A collaboration with The Writing and Society Research Centre, Western Sydney University.

How do you define a city? It depends on who you ask and when you ask them.

As a child, I often travelled from the small coastal town where I was born to visit family around the Parramatta and Blacktown areas, as well as in Penshurst and Hurstville and the Inner West. I viewed each residence as roughly the same, all located in Sydney, the big smoke, the perceived land of opportunity. I felt I needed to escape the place I was born to move to Sydney, anywhere in Sydney, to become educated and find work and live a ‘good’ life. It wasn’t until as a young adult, when I did exactly that, I realised the Sydney I saw as a cohesive unit was so clearly demarcated.

Someone I met that first year at the University of Sydney proudly told me he’d never been further south or west than the campus itself, a claim I initially didn’t quite believe. Parramatta wasn’t his city, and if it was mine ‒ because it was, at that point, the Sydney I knew most intimately ‒ then I mustn’t belong to his, which mainly existed north of the bridge. All of this felt ludicrous to me, coming from the country. The campus was only an hour away from Parramatta on the train, roughly the time I’d spent travelling to school each morning on the bus back at home.

We can also understand a place through our connection to the people who live there. And communities are never a uniform group, but rather individuals with their own unique histories and relationships to the land they live with and depend on.

I see now how these interactions from when I was younger illustrate the way a place is so often defined by outsiders based on their homogenised understanding of the people who live there. My university peer saw Parramatta as a place that was ‘other’, filled with people not like him, with whom he had no relationship. But we can also understand a place through our connection to the people who live there. And communities are never a uniform group, but rather individuals with their own unique histories and relationships to the land they live with and depend on. We hear their stories about a place, with all their minute and innocuous details, and our own stories begin to wrap around them. Even if we are not from or haven’t lived in that area ourselves, through our relationality we can have an understanding of how to relate to that place.