After the no vote

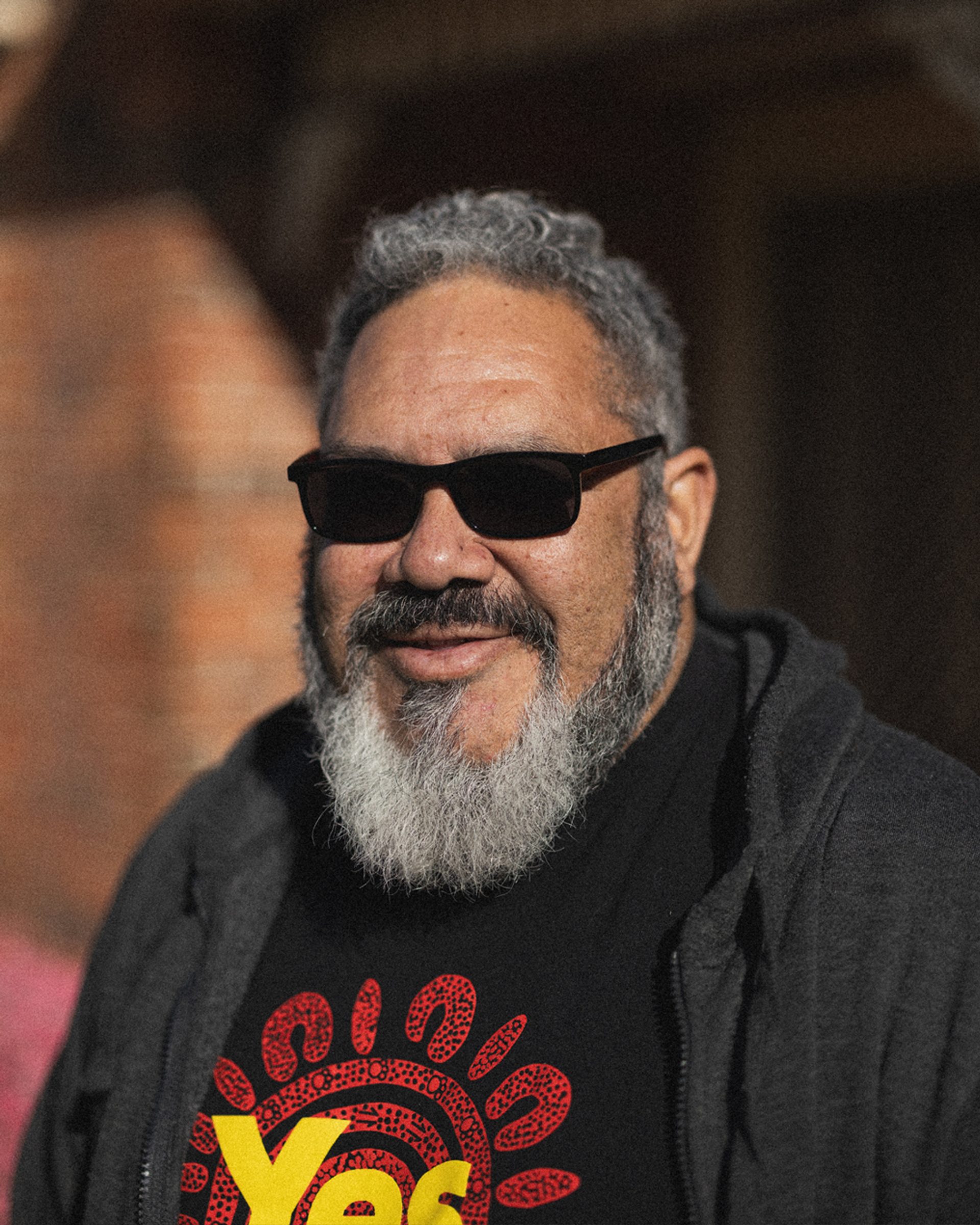

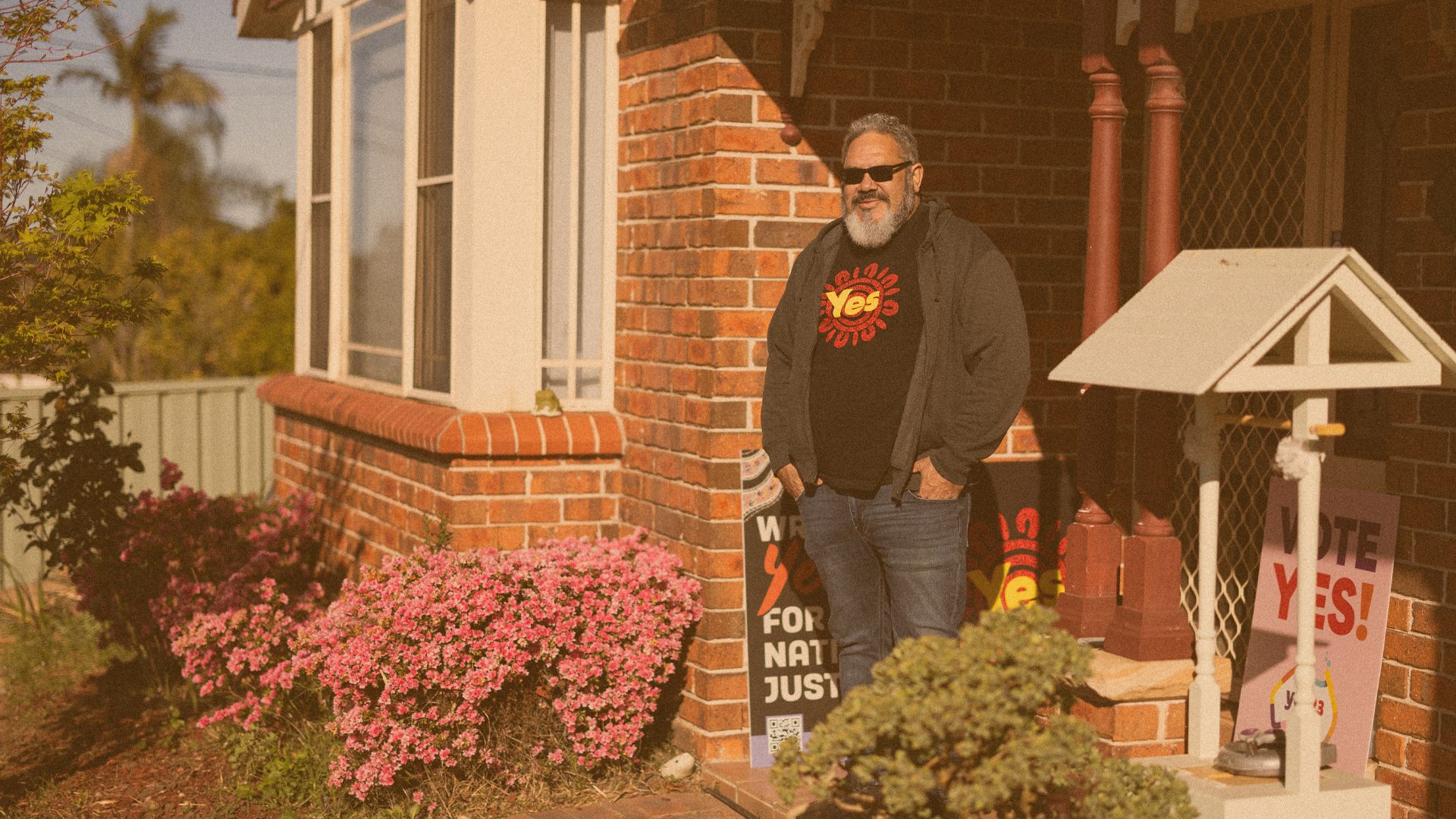

Matt Wildig, a Palawa writer, is inspired by Voice to Parliament campaigner and Meriam man Gav Harris and his work as an advocate for First Nations people.

Despite the momentary cold snap that hung over Parramatta a few days before, it’s a hot day, and I’m sweating as I sip my coffee and pass my list of questions to Gav Harris. I can’t help but wonder if the cafe has even turned on the air conditioner and I’m worried that asking a man who’s just gotten out of the hospital to meet up for a chat about his work on the First Nations Voice to Parliament campaign was a bad idea. But Gav tells me he prefers a face-to-face conversation and that being out of the house is a good thing.

Gav grew up in North Queensland in the 1970s with his adoptive parents in a social landscape that was even more restrictive than it is today. His people are from Murray Island in the Torres Strait. Like many other Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders during the 1980s, Gav was not heard. His voice was discouraged and he became a victim of the social oppression that continues to dictate the lives of many Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders today.

Ideally, school life should’ve offered a respite from the racism of general society, but it didn’t; instead, as a teenager he was told by a teacher that he wouldn’t grow up to be anything special. This prompted his father to tell him that he would be battling these kind of racial stereotypes throughout his life. So Gav decided to keep his head down. He stayed away from the police, focused on the strengths he had, and realised that if he wanted to progress and get ahead he had to play the game – which is exactly what he did.

He moved to Brisbane to study a Bachelor of Arts focusing on English at the University of Queensland and joined a punk band. He wanted to show everyone who viewed him through a stereotypical lens that he could achieve great things. He’s excelled in his professional work as a technician and his advocacy work with the Voice campaign.

You might assume that someone so rooted in the fight for a parliamentary voice for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islanders would have already considered himself an advocate for his people. But while Gav had always been politically aware and engaged in Indigenous politics– whether it was attending rallies for Indigenous land rights or against Indigenous deaths in custody – becoming a spokesperson for the Voice campaign took him by surprise.