Paving Parra

Working as a contractor on some sites around the revitalisation of Parramatta City brought Bruno Stramandinoli back to the area where he grew up.

Trying to find parking around Westmead Health Precinct is like pulling teeth. When I arrive at Leaf Café, I apologise for its location. Stirring a long black, Bruno Stramandinoli raises his eyebrows. ‘I thought you picked this place on purpose.’

Opposite the cafe entrance, a row of elevators carries academics and health professionals up and down the university building. In 2021, Bruno paved the elevator floors. Right outside where we sit, nurses on their lunch break sit on a raised deck centred around a teenaged tree. Bruno built that too.

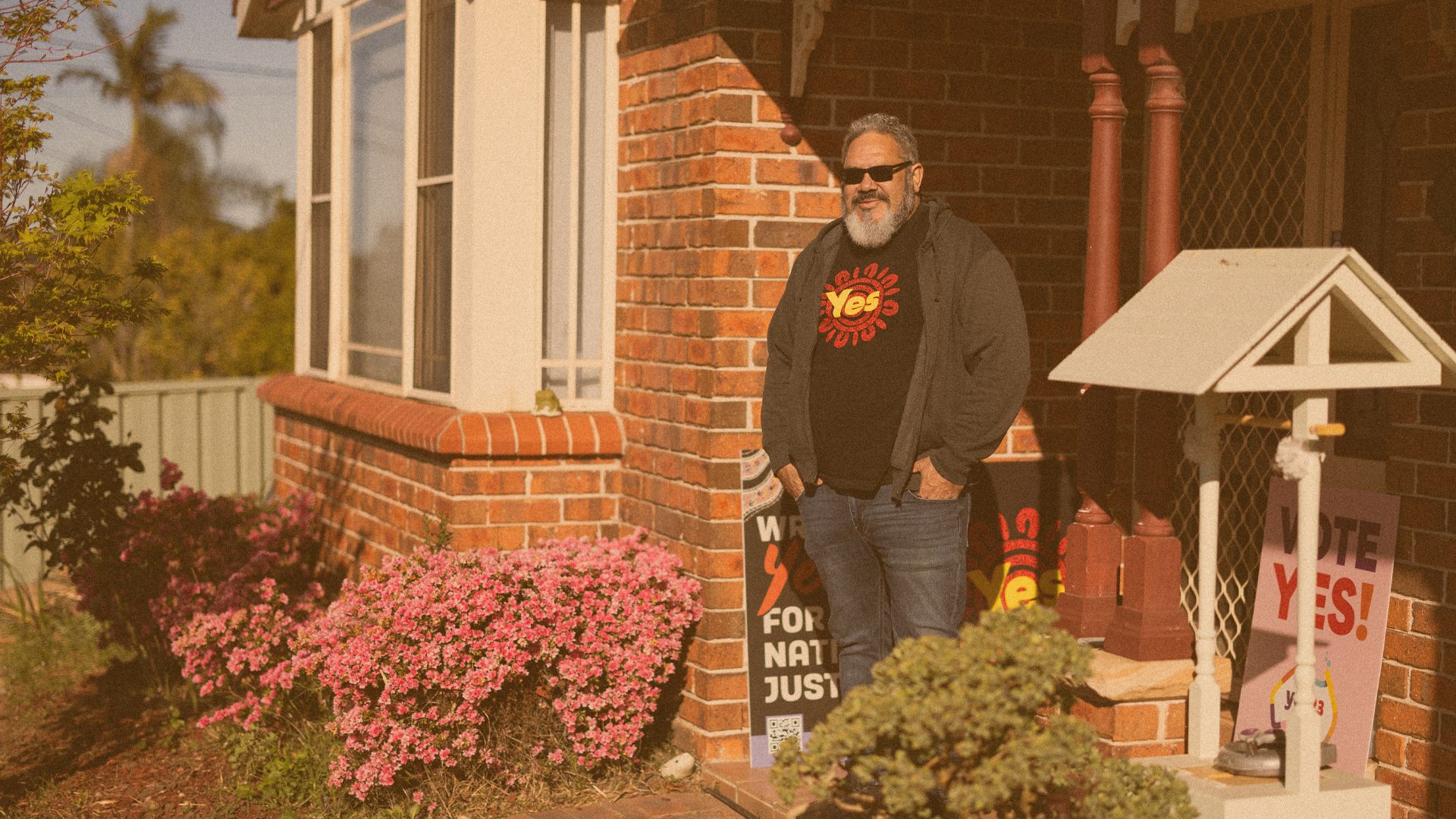

I met Bruno through my partner Mason; they’re stepbrothers. When I have time to drop Mason, a nurse, off for his afternoon shift at Westmead Hospital we eat lunch together on the decked planter box. Bruno has been a landscaper since his early twenties and owns a small business. He grew up between Penrith and Pendle Hill but now lives in the Inner West, and in recent years he’s worked on some prominent projects in Parramatta CBD. I ask Bruno about the decking. Smiling, he pulls out his phone. In between photos of his 3 year old son Gabriel’s smiling face and blonde ringlets are pictures of dissected floors and bundles of steel.

A bona fide storyteller, Bruno analogises each step of the construction process. ‘The whole area (1.5 square metres of soil) is similar to what’s at Parramatta Square. The garden bed itself had to be waterproofed – a ball-ache of a job.’

To prevent any damage to the waterproofing, landscapers first use corflute liner. ‘It’s the same material as election placards, you know, the ones on fences that say, “Vote for such-and-such”.’ Next, the lining of Geotech fabric is like a coffee filter, allowing water to trickle through soil. The layer of sand is another filter (this time a Britta) and the actual tree itself is ‘the good stuff’. The layered sediment under the decking is as complex as it is unseen, but the gist is this: where water enters, water must exit.