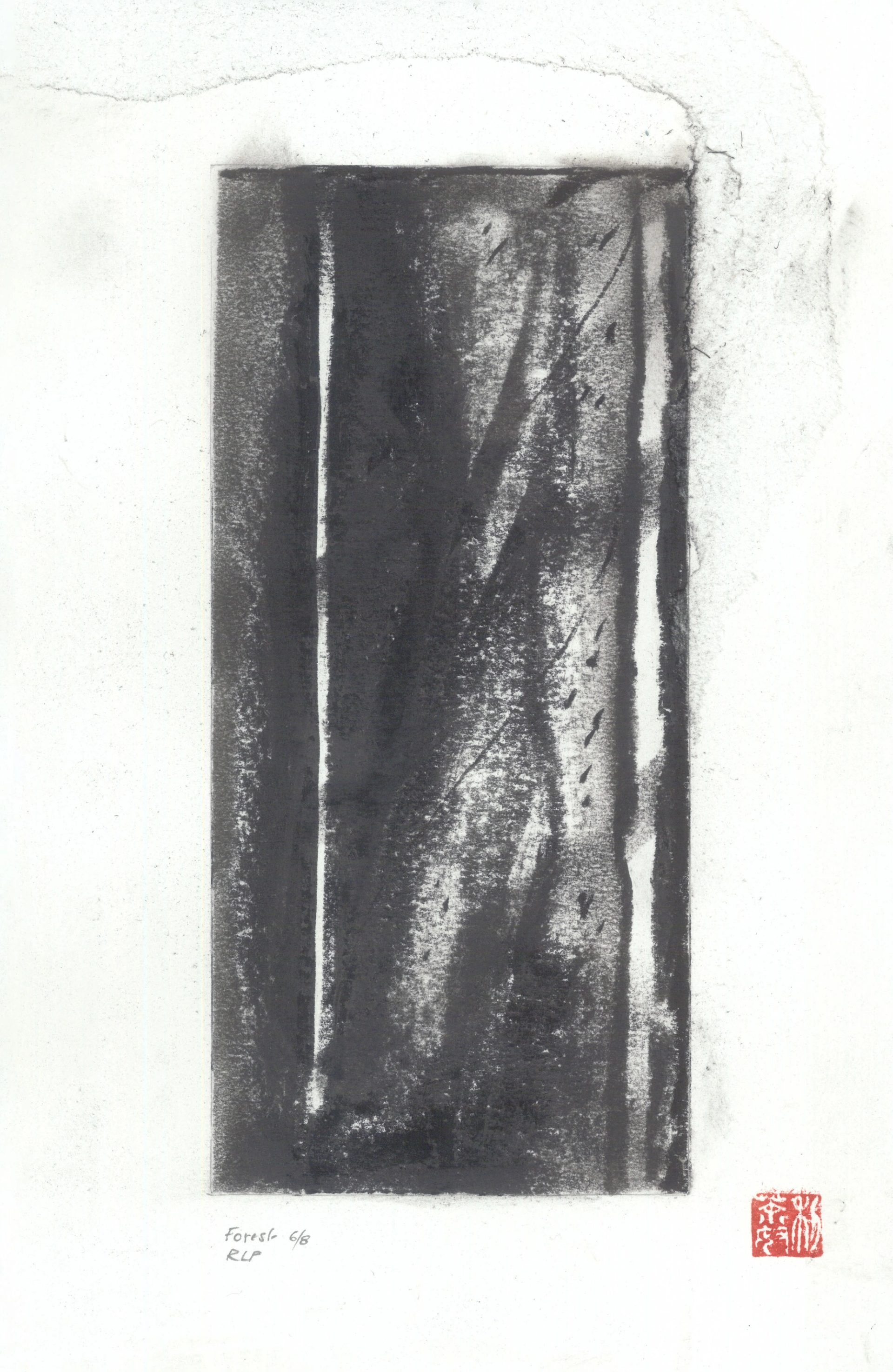

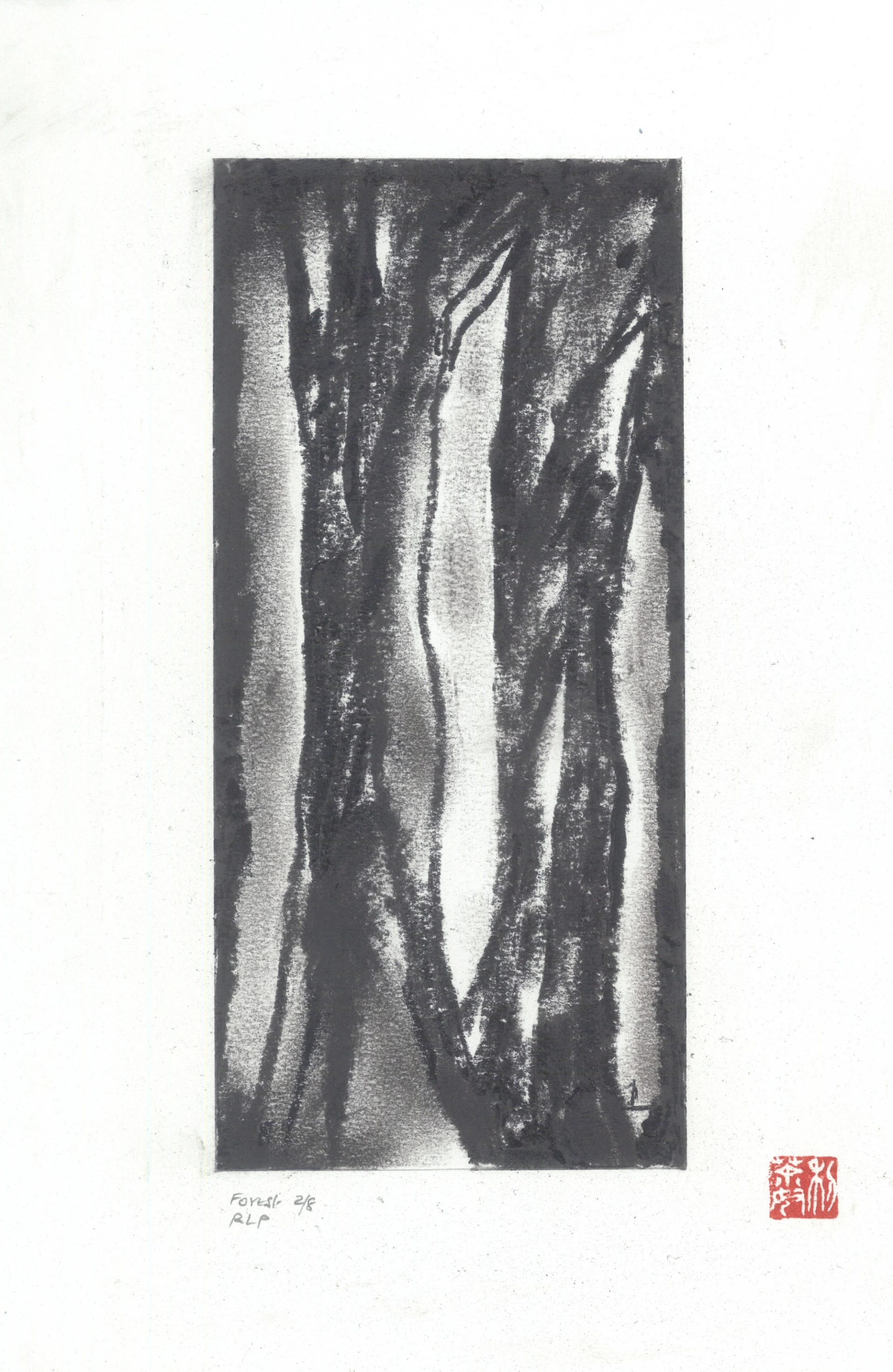

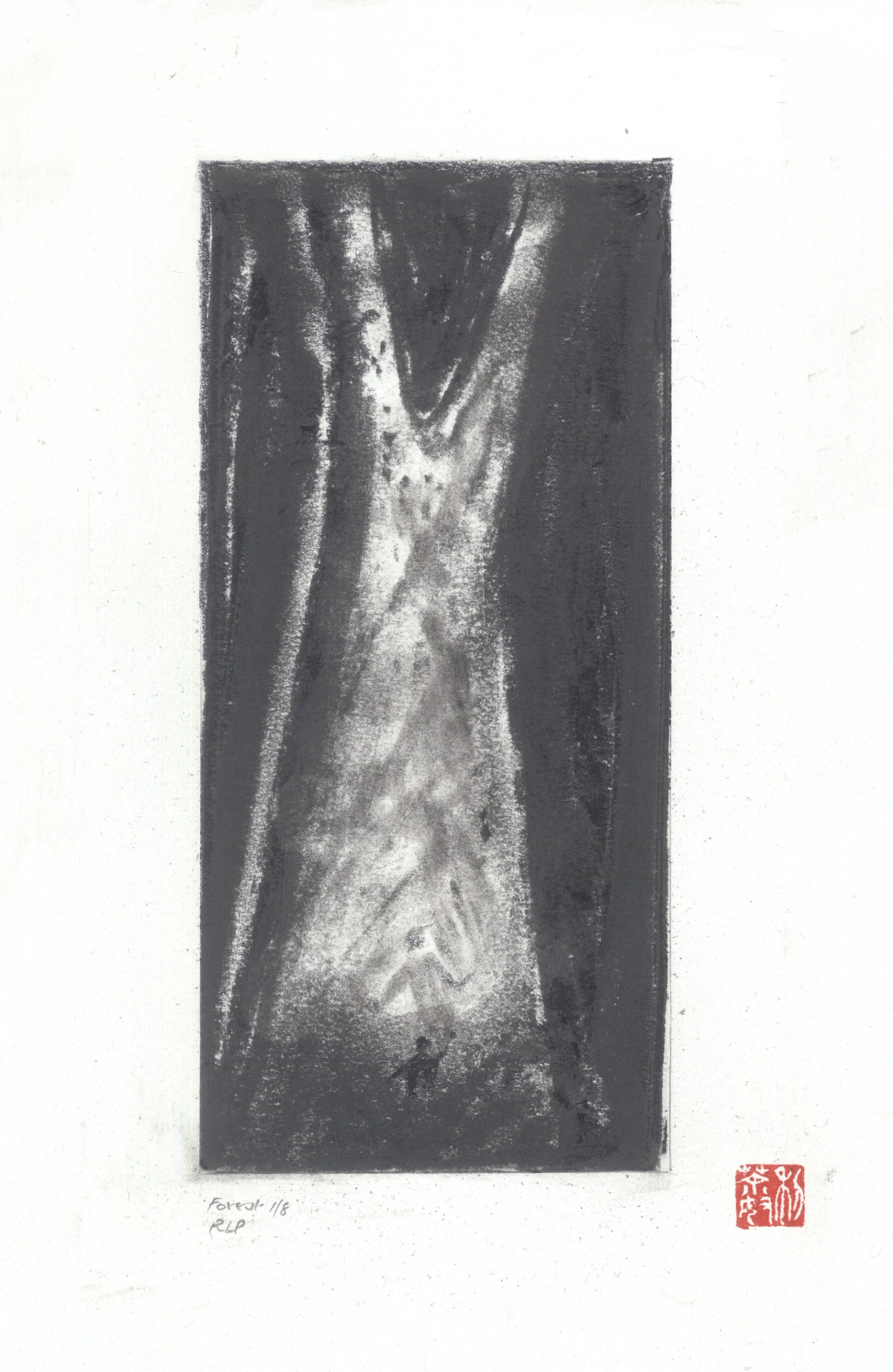

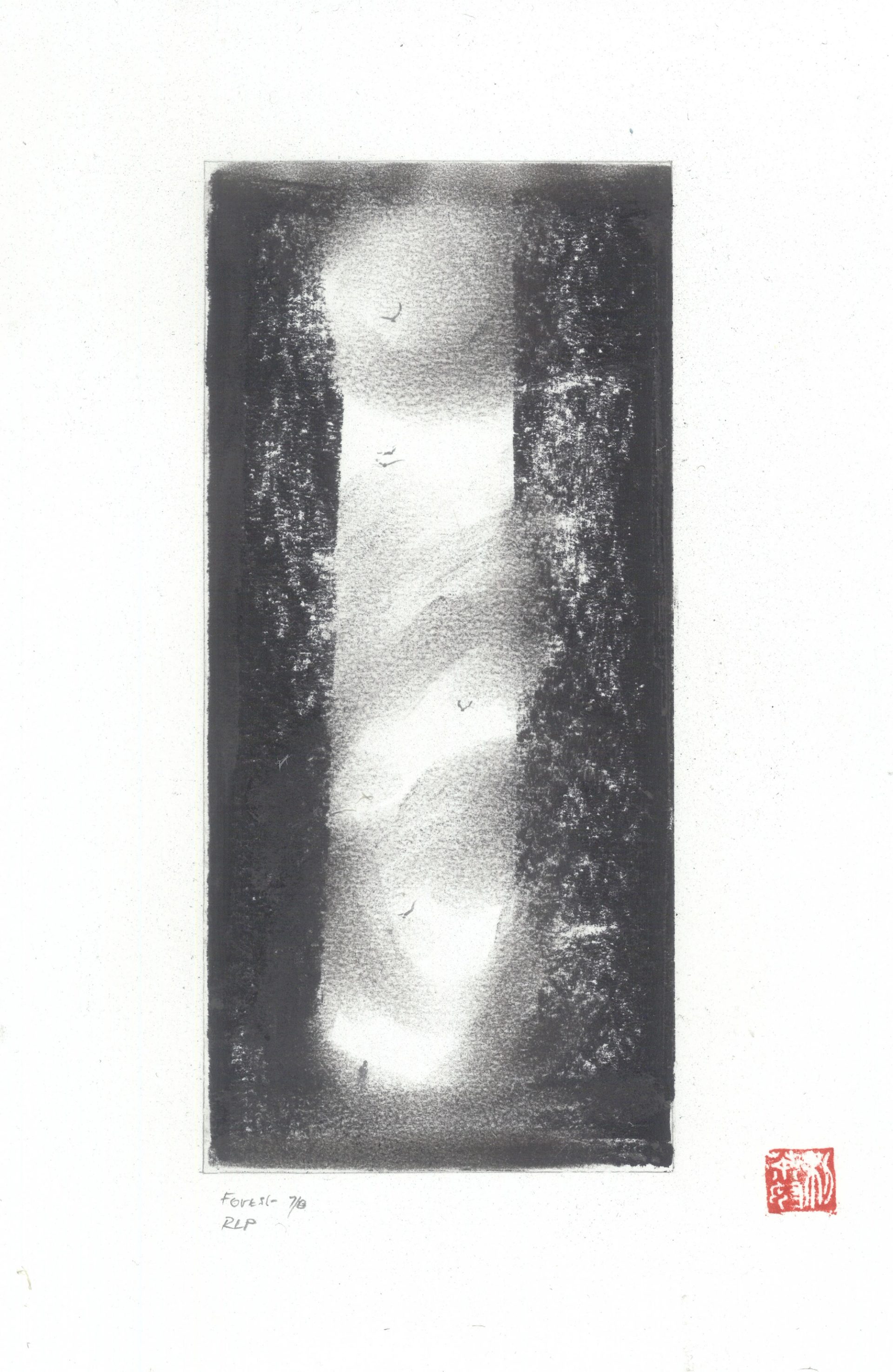

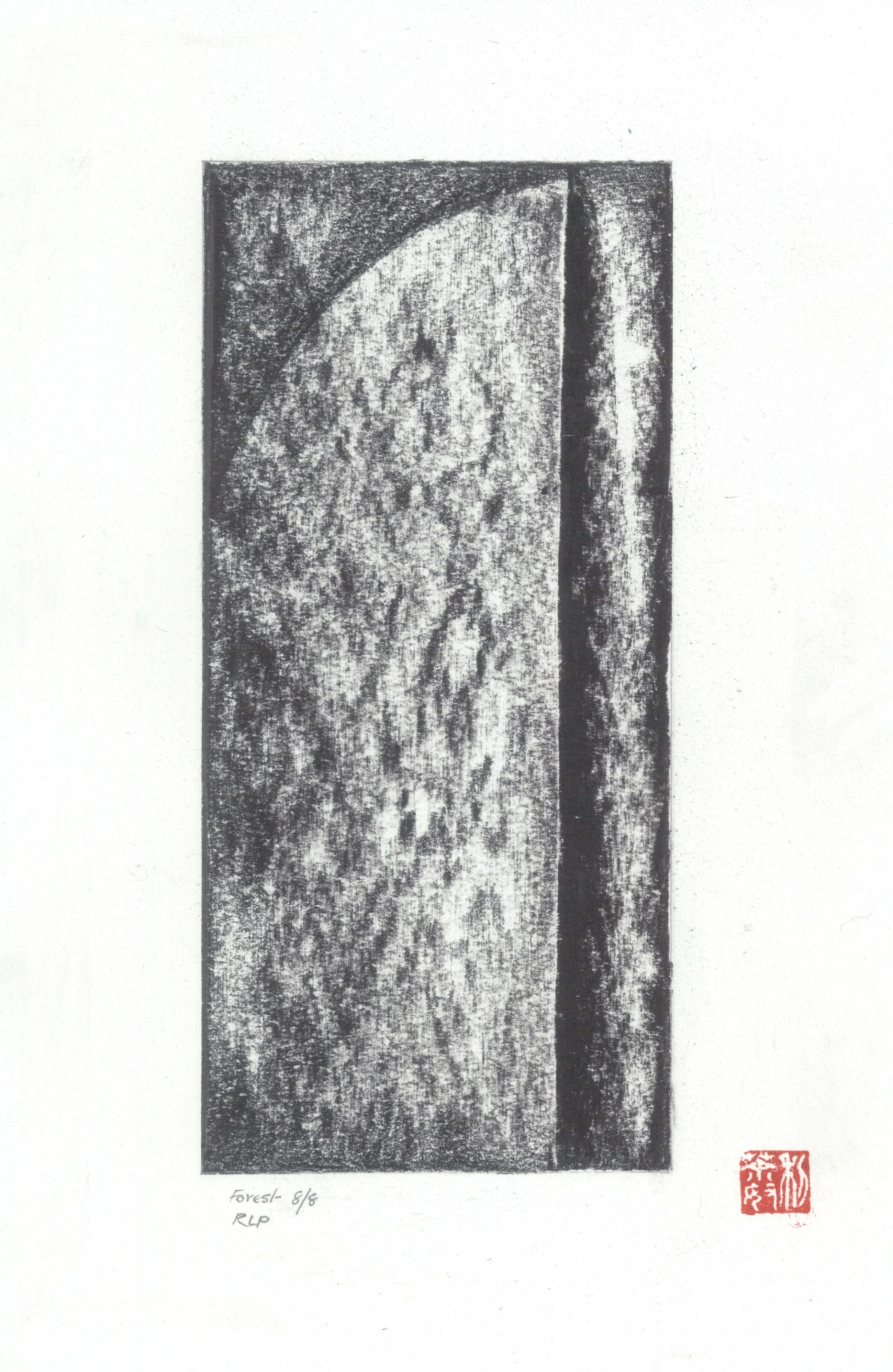

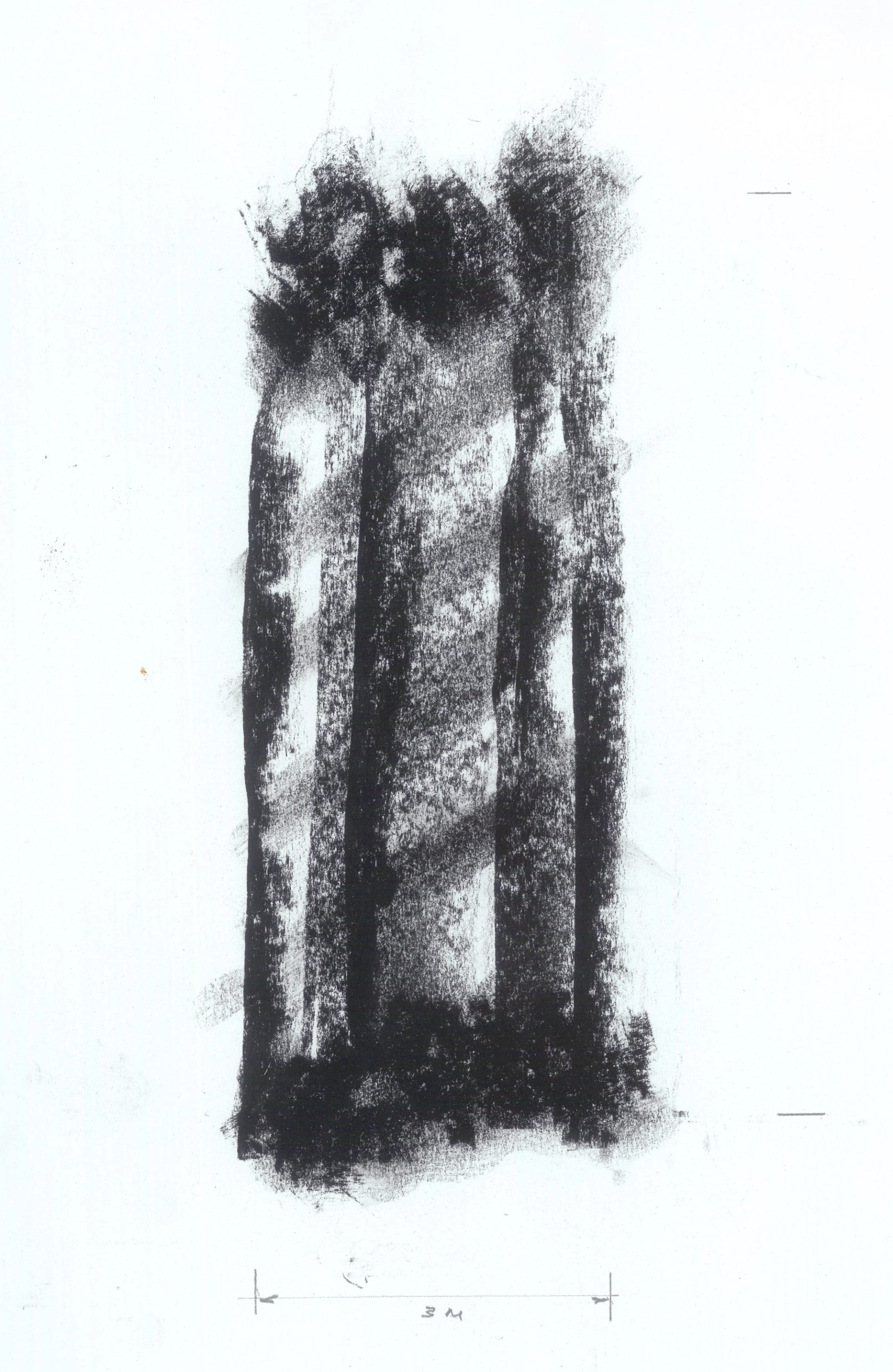

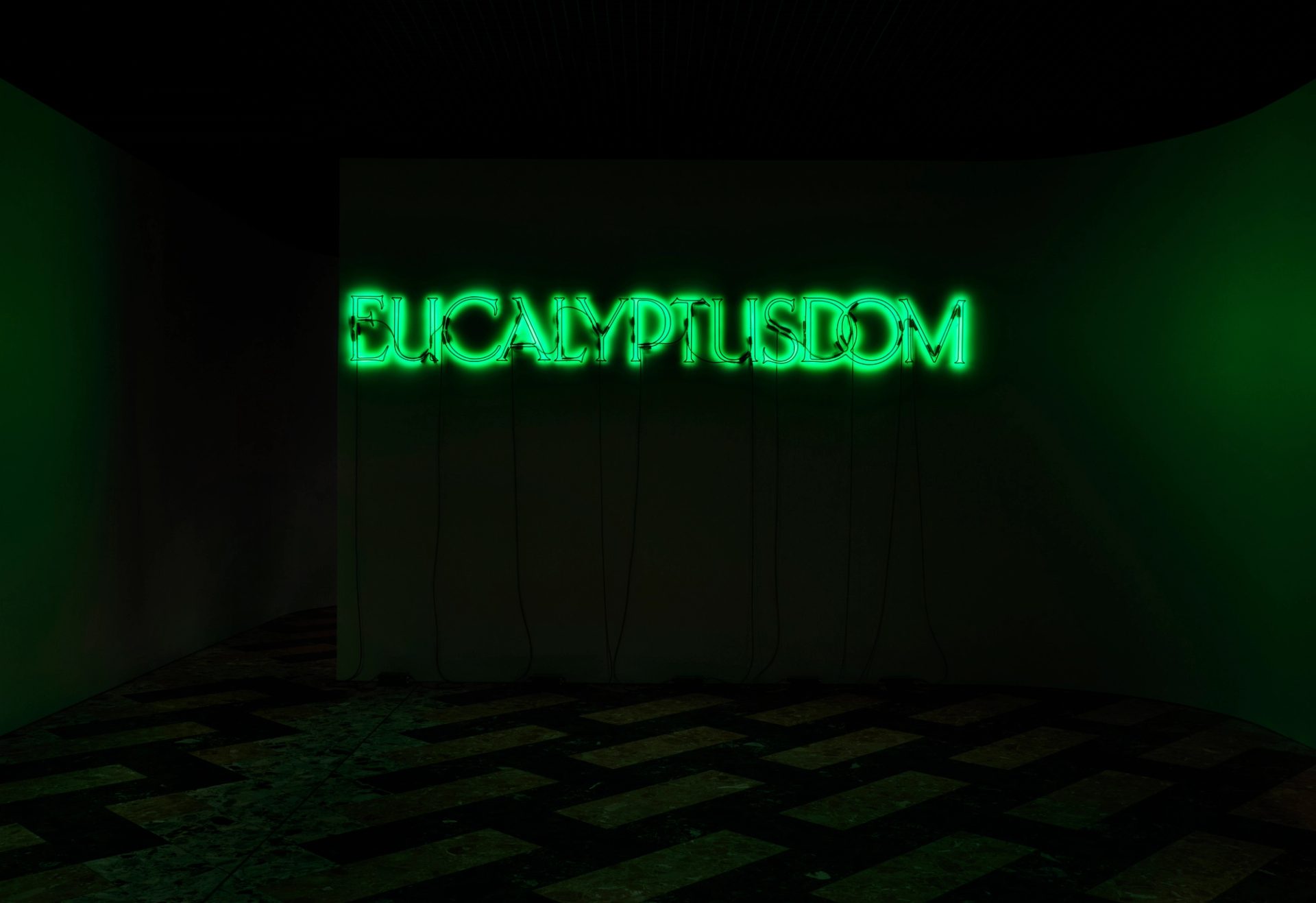

The Ethos of the Forest

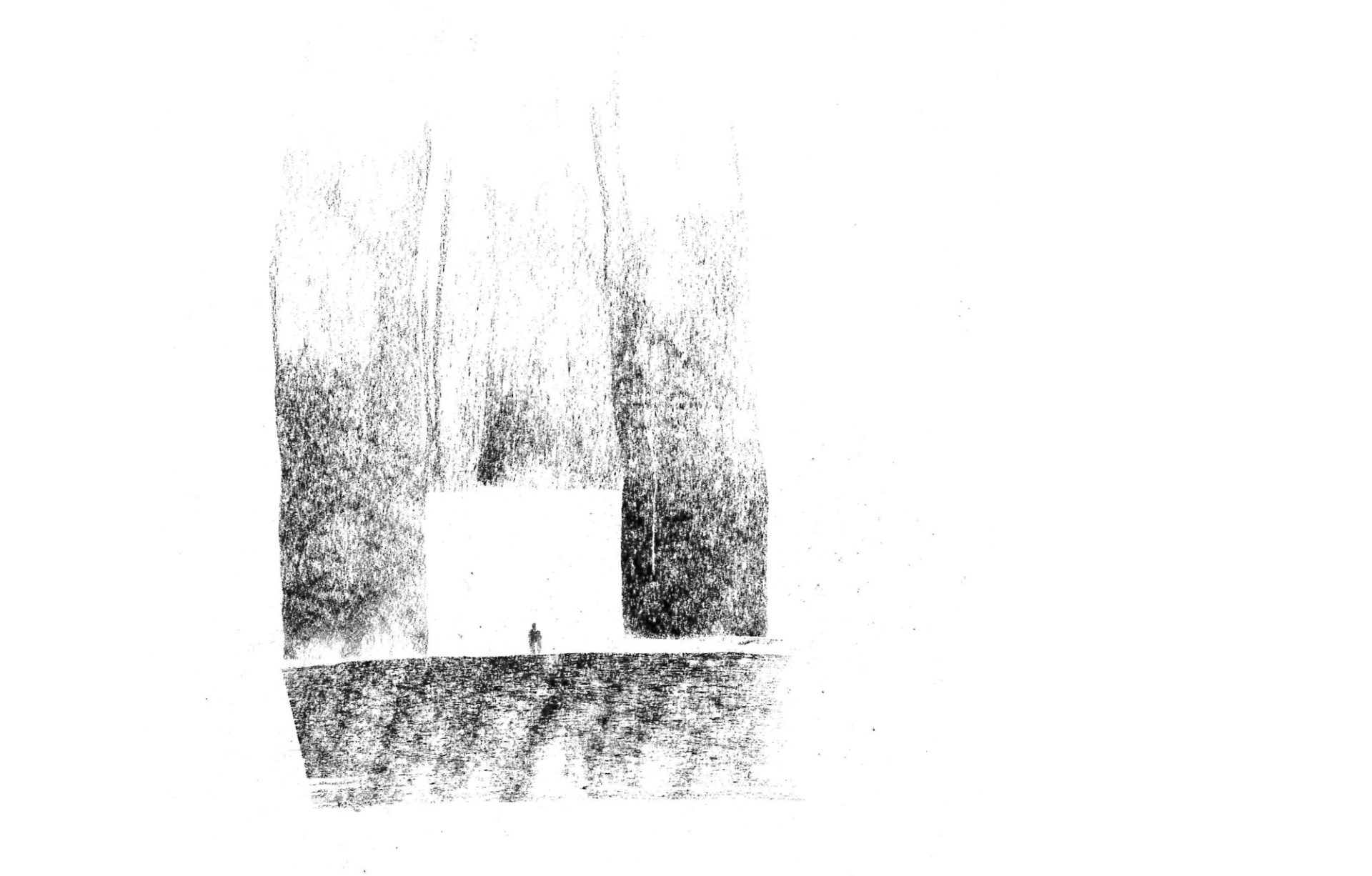

‘They are drawn from my mind. I walk the forest around my home all the time, but the drawings are to evoke the feeling of any eucalypt forest.’

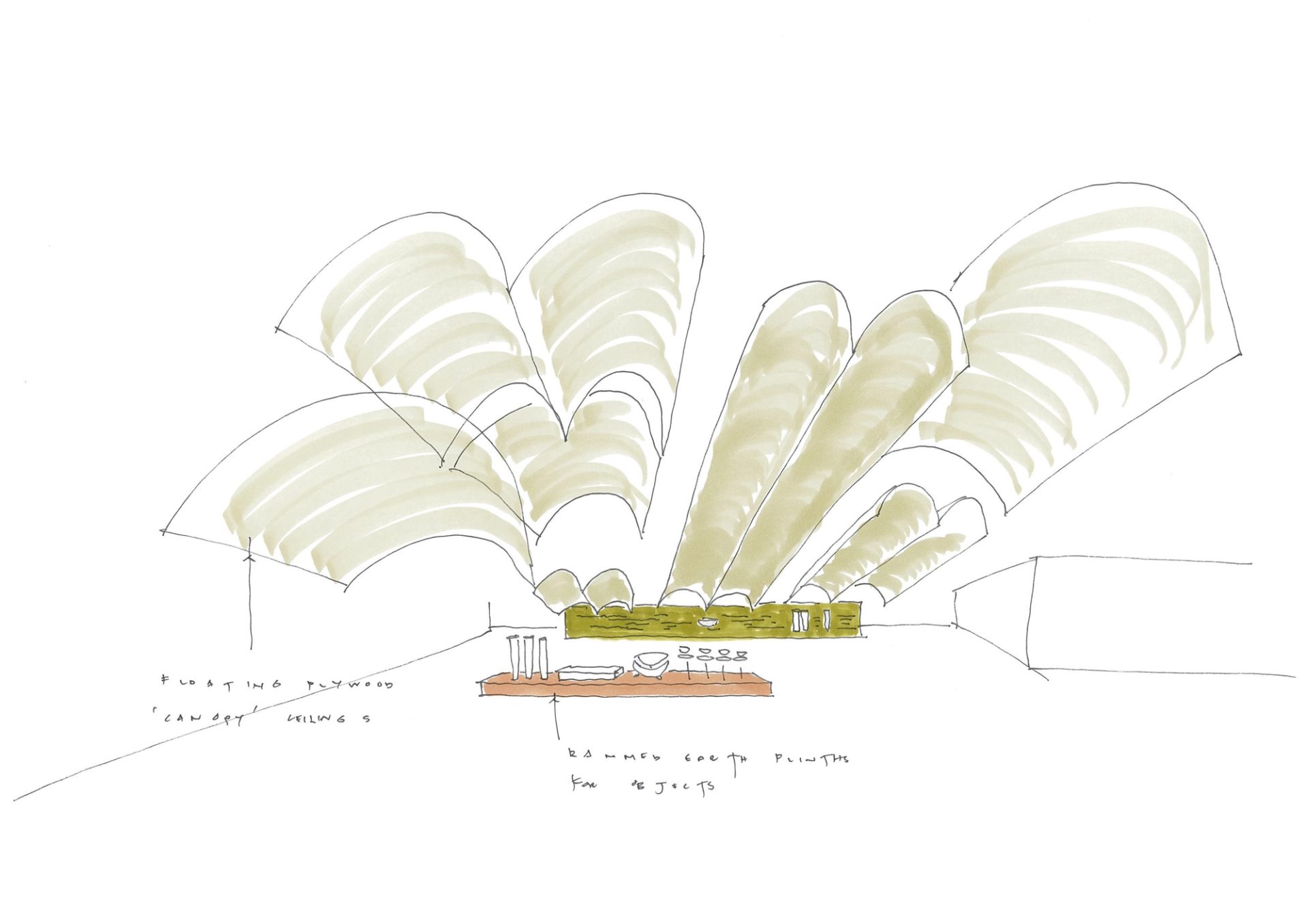

The Eucalyptusdom exhibition design team – led by Adam Haddow and Jack Gillmer of SJB in collaboration with Richard Leplastrier AO and Vania Contreras – recently won the interior-temporary category at the World Architecture Festival 2023. In this extract from the exhibition’s companion publication Eucalyptusdom (Powerhouse Publishing, 2022) Gillmer and Leplastrier share how their collaboration began and discuss some of the principles that underpinned their approach.

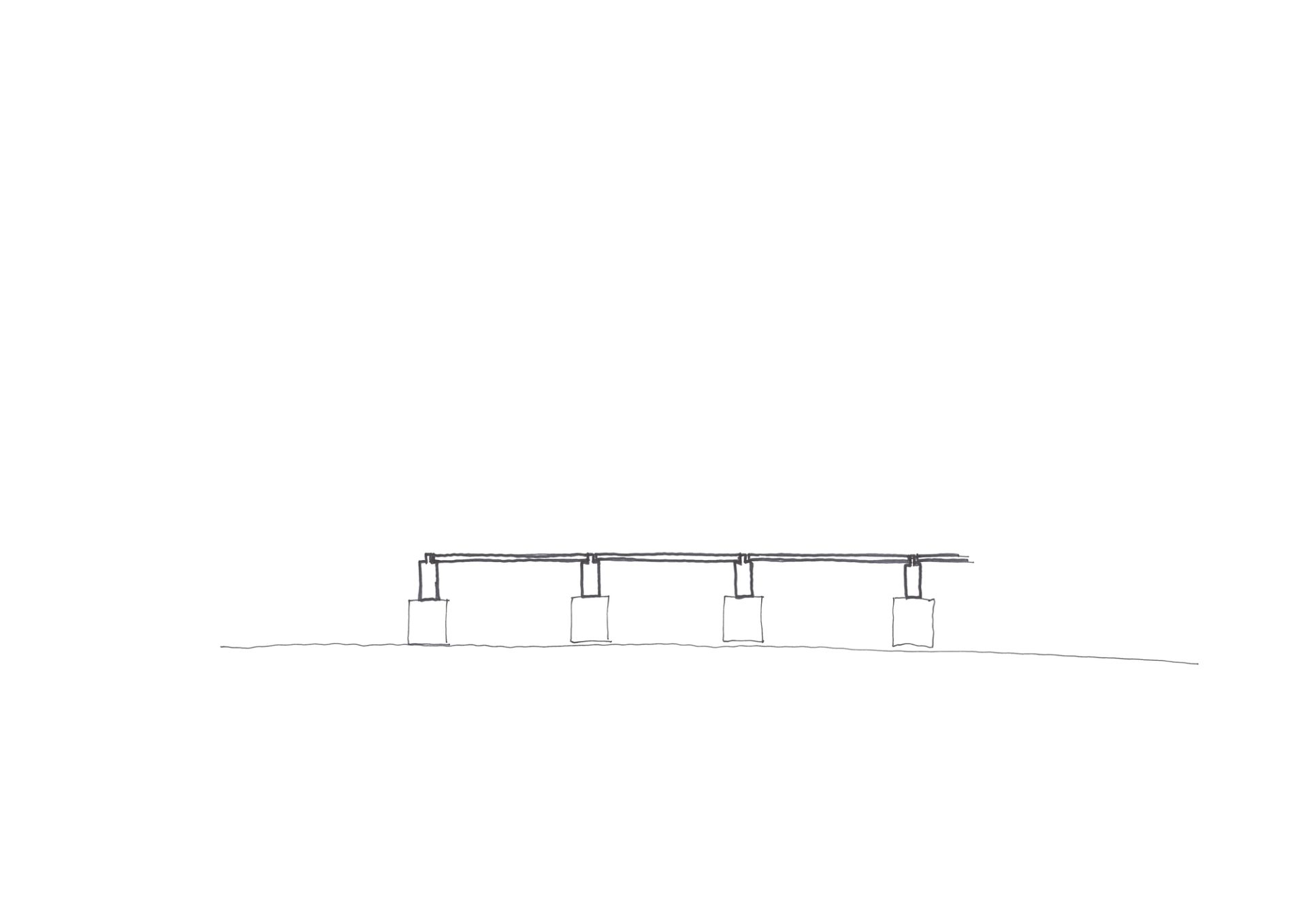

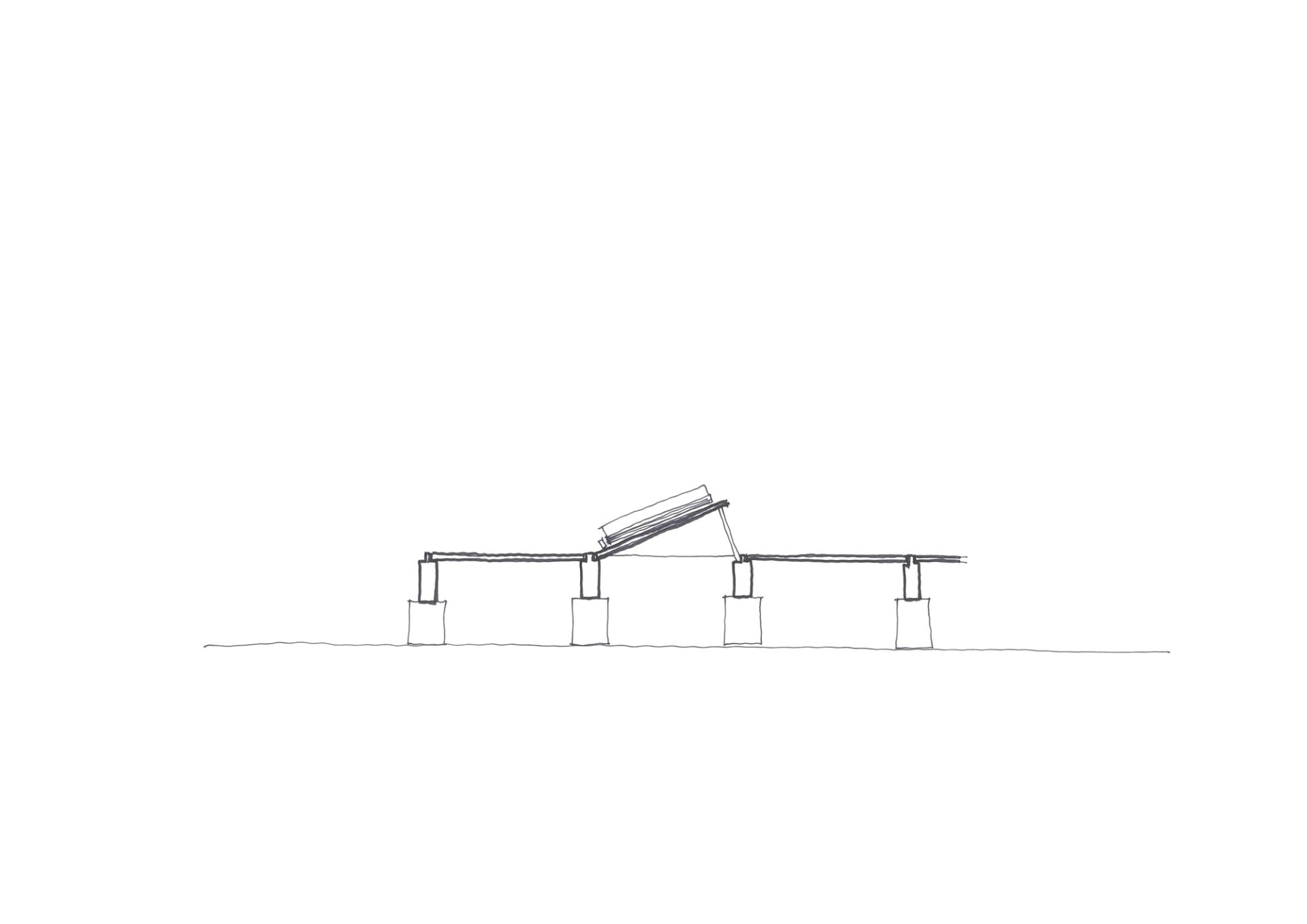

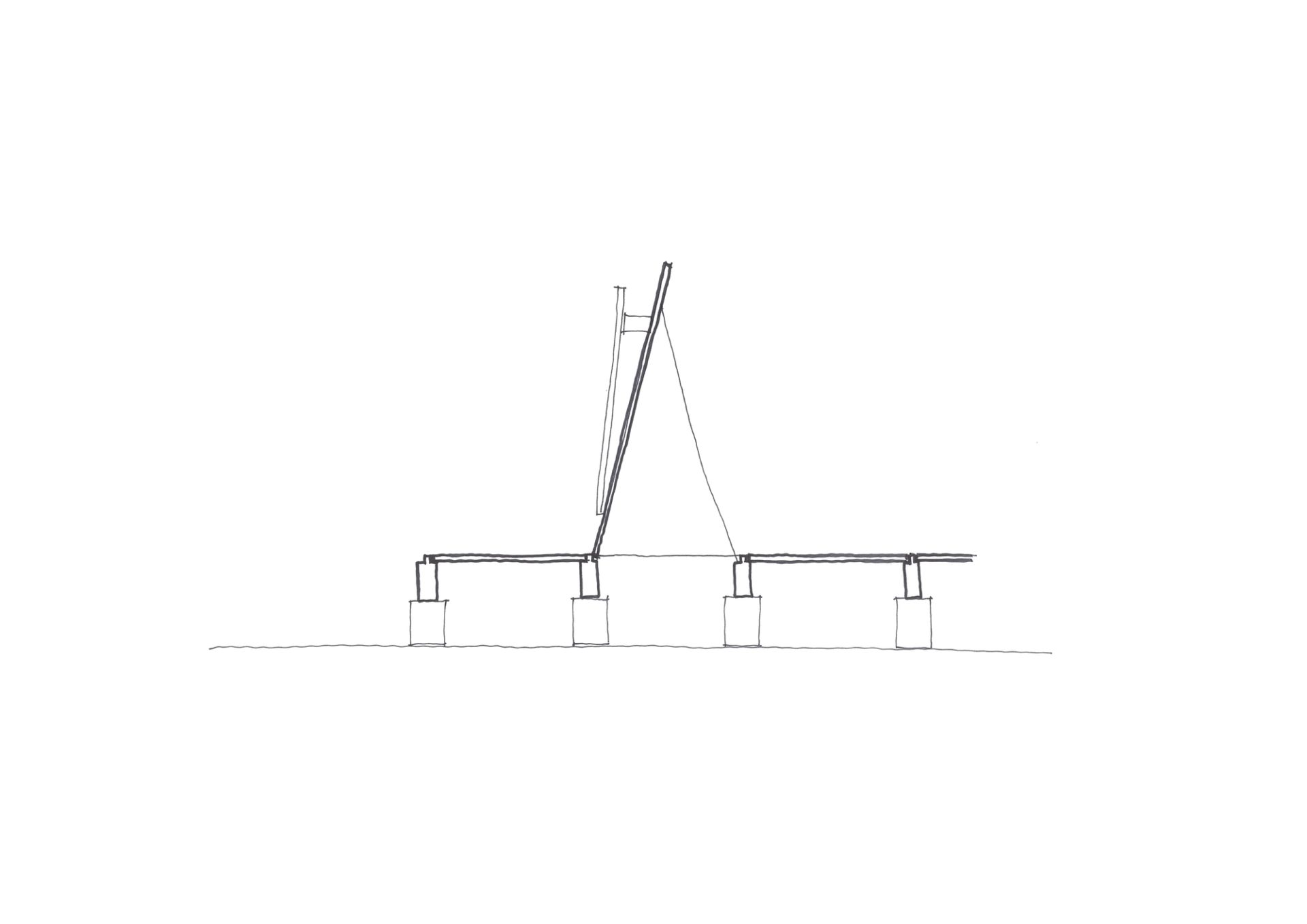

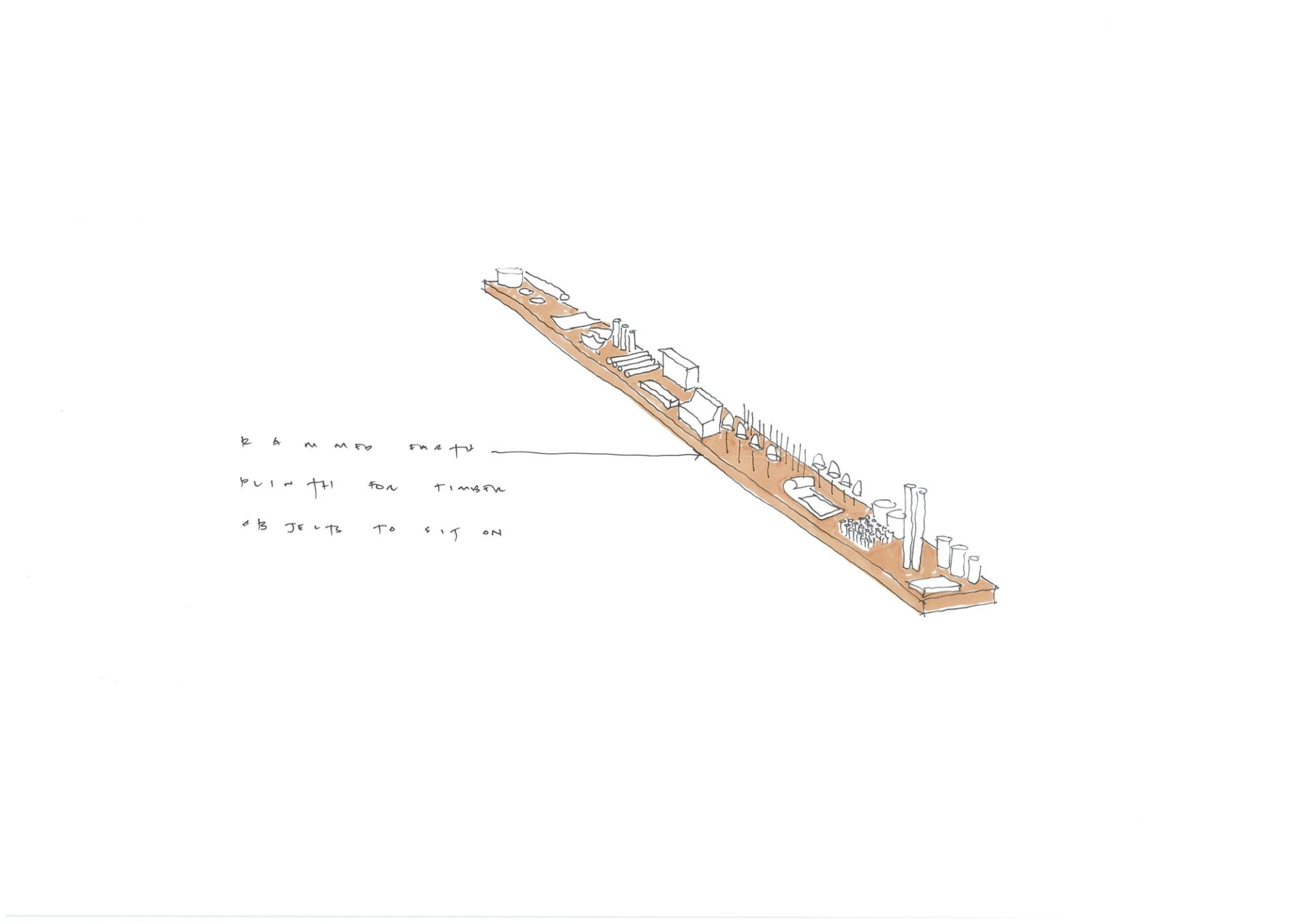

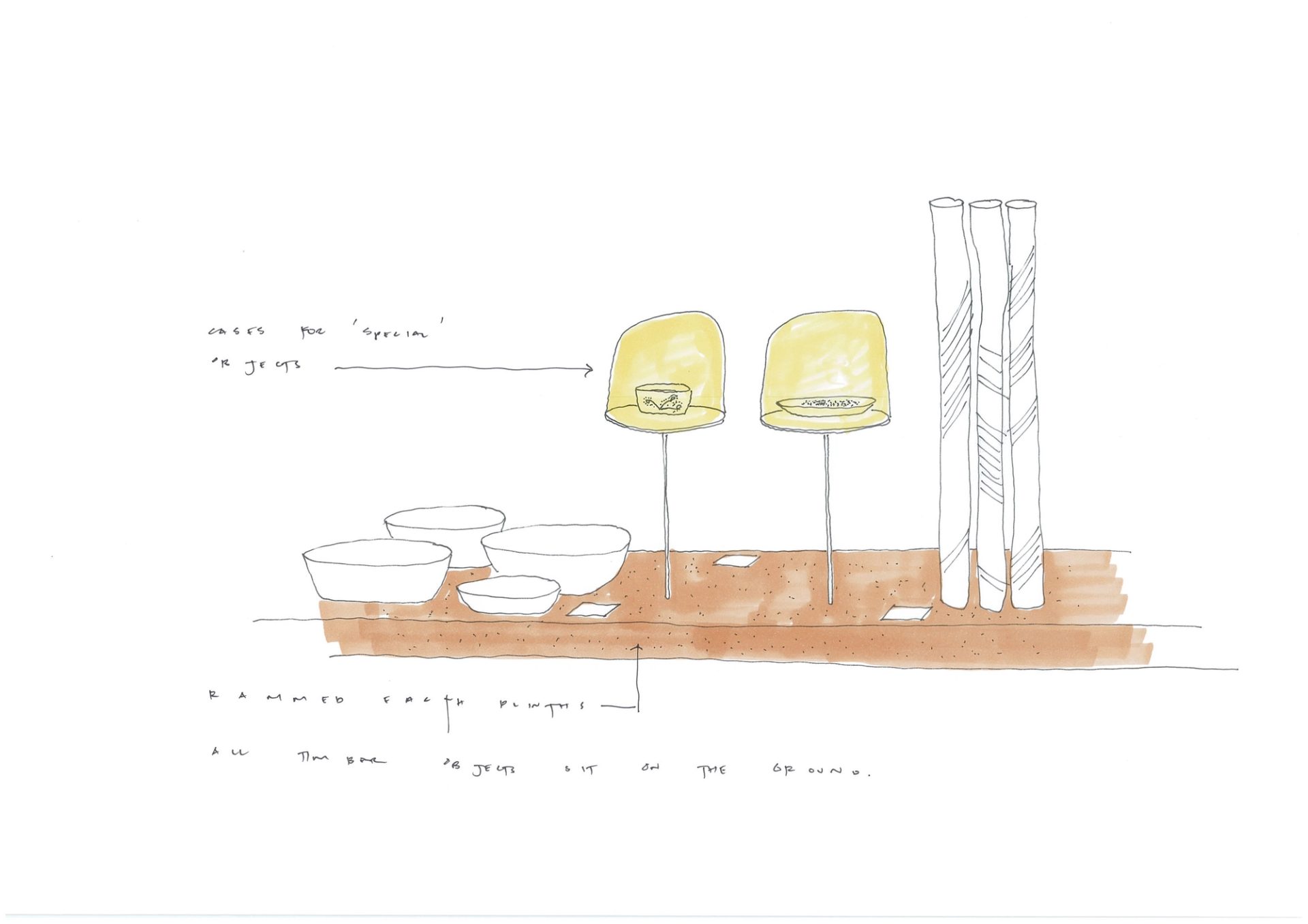

Exhibition design is often thought of as scenography; a set upon which theatrics can happen. Eucalyptusdom was instead conceived of as a terrain, a landscape that the audience — no longer just a viewer — could explore.

Jack Gillmer I remember when we met — I was in fourth year of my architecture degree at the University of Newcastle, where you were teaching, sharing knowledge. We were upstairs on the mezzanine, our first conversation was not about buildings, but about plants, forces of nature. Specifically, the Moreton Bay fig tree; the way it deals with the pressures of wind and tectonic shifts by developing massive buttress roots that support it. You did a beautiful sketch, which still inspires my architectural thinking.