Collection Curation

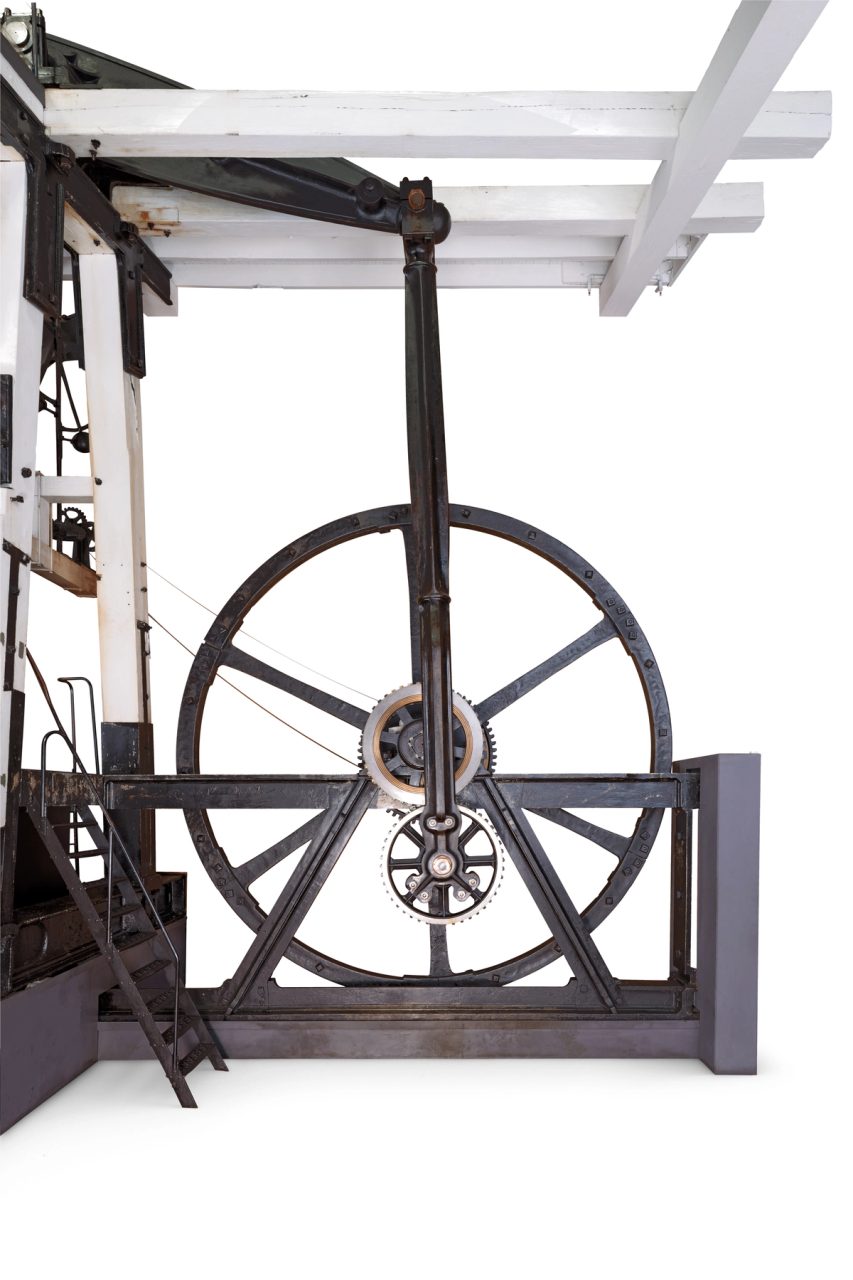

Come behind the scenes at Powerhouse Castle Hill and meet some of the people who work with the Powerhouse Collection.

Curators at Powerhouse develop, care for and interpret the collection. They manage object acquisitions or loans, conduct research and share knowledge about objects for exhibitions, educational programs and publications, and collaborate on tours and displays. Curators often bring a combination of subject matter expertise and academic analysis of social issues to their work. Storytelling about collection objects helps expand audiences’ awareness and understanding of their cultural importance across time.

Nathan Mudyi Sentance

Head of Collections First Nations

‘My passion is storytelling and truth telling which go hand in hand. My role at Powerhouse allows me to care for First Nations stories, which as a Wiradjuri man, an Aboriginal man, is an incredible privilege but also a great responsibility. I need to ensure the stories we hold are cared for in a way that respects First Nations sovereignty, protocols and rights. We cannot let these stories gather dust. In collaboration with the relevant First Nations community, we will work to get them heard and engaged with.

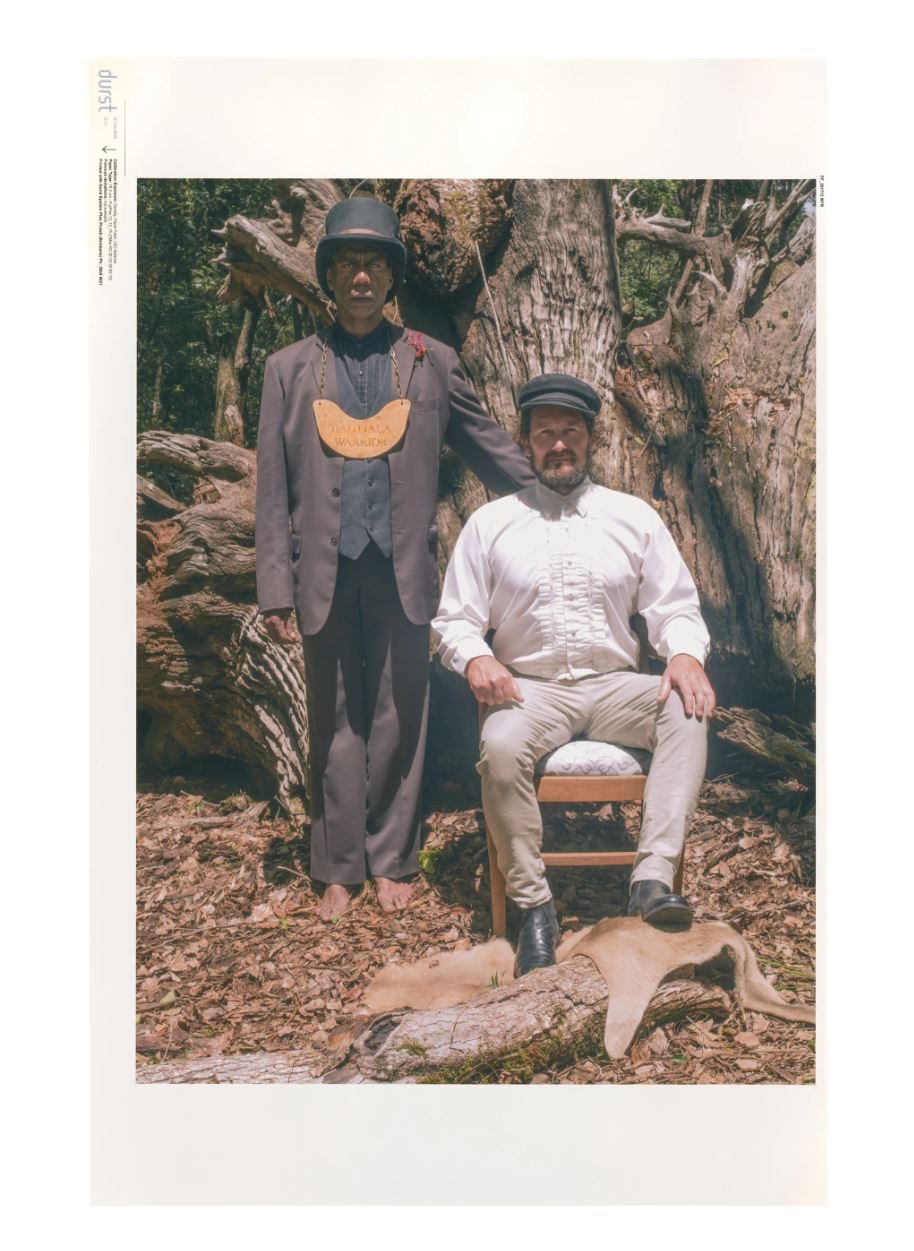

I've chosen three examples from the collection. I chose ‘Protector and Aborigine’ photographic print because Dr. Fiona Foley is a legend. Their work often tackles history that Australians look away from. It is the truth telling I hope Powerhouse can engage in more.’