Collection Research

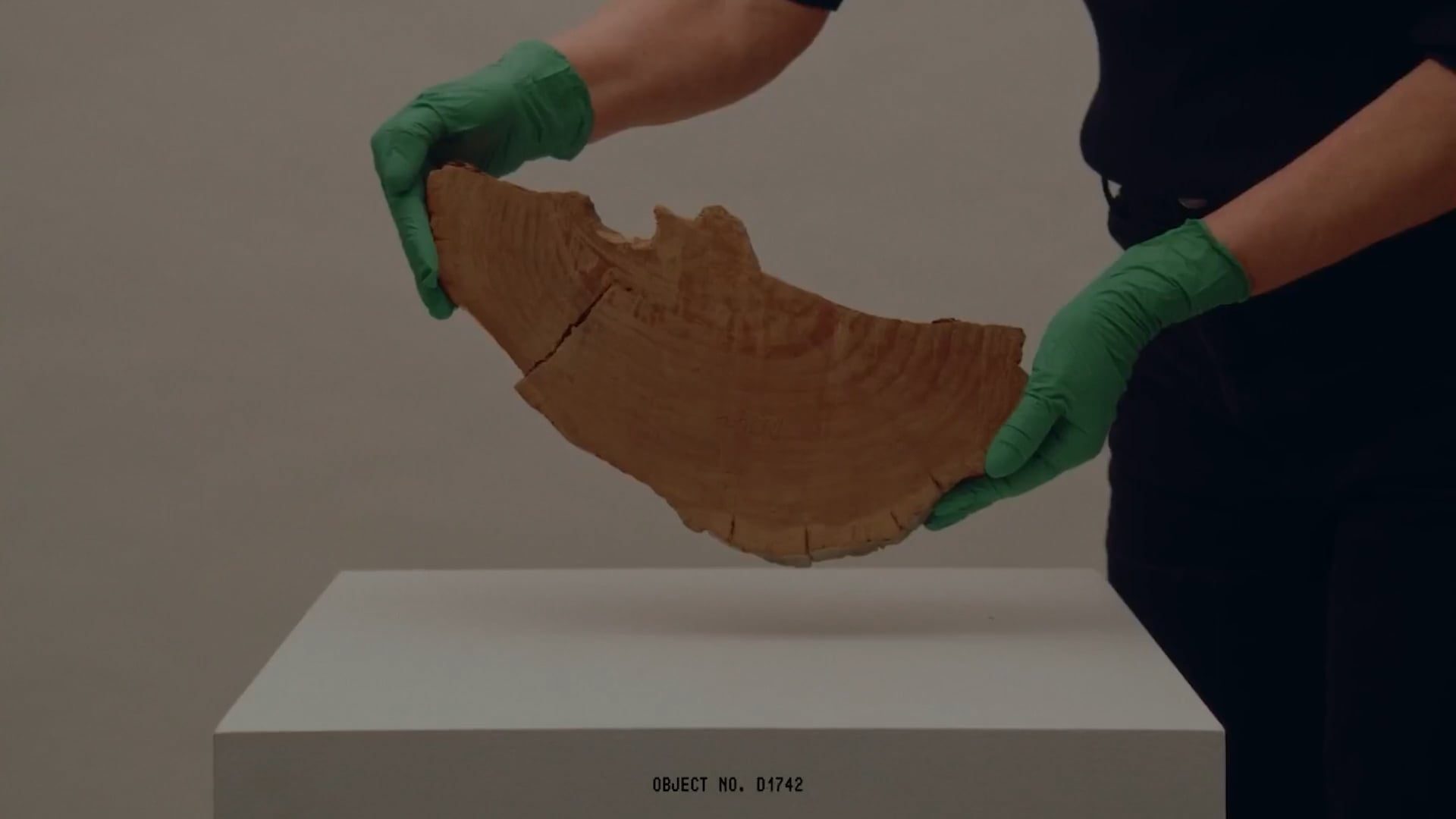

Come behind the scenes at Powerhouse Castle Hill and meet some of the people documenting and caring for the Powerhouse Collection.

Researchers at Powerhouse create, collect and enhance knowledge in multiple disciplines across the applied arts and sciences. Important focus areas include First Nations, sustainability and Western Sydney. They frequently collaborate with peers in industry, community and academia on long-term research projects, and their insights are shared through exhibitions, symposiums and education programs. The Powerhouse Research Program, which is designed to create new pathways for future thinking and provide new contexts for the Powerhouse Collection, is also responsible for the Powerhouse Research Library, records and archives.

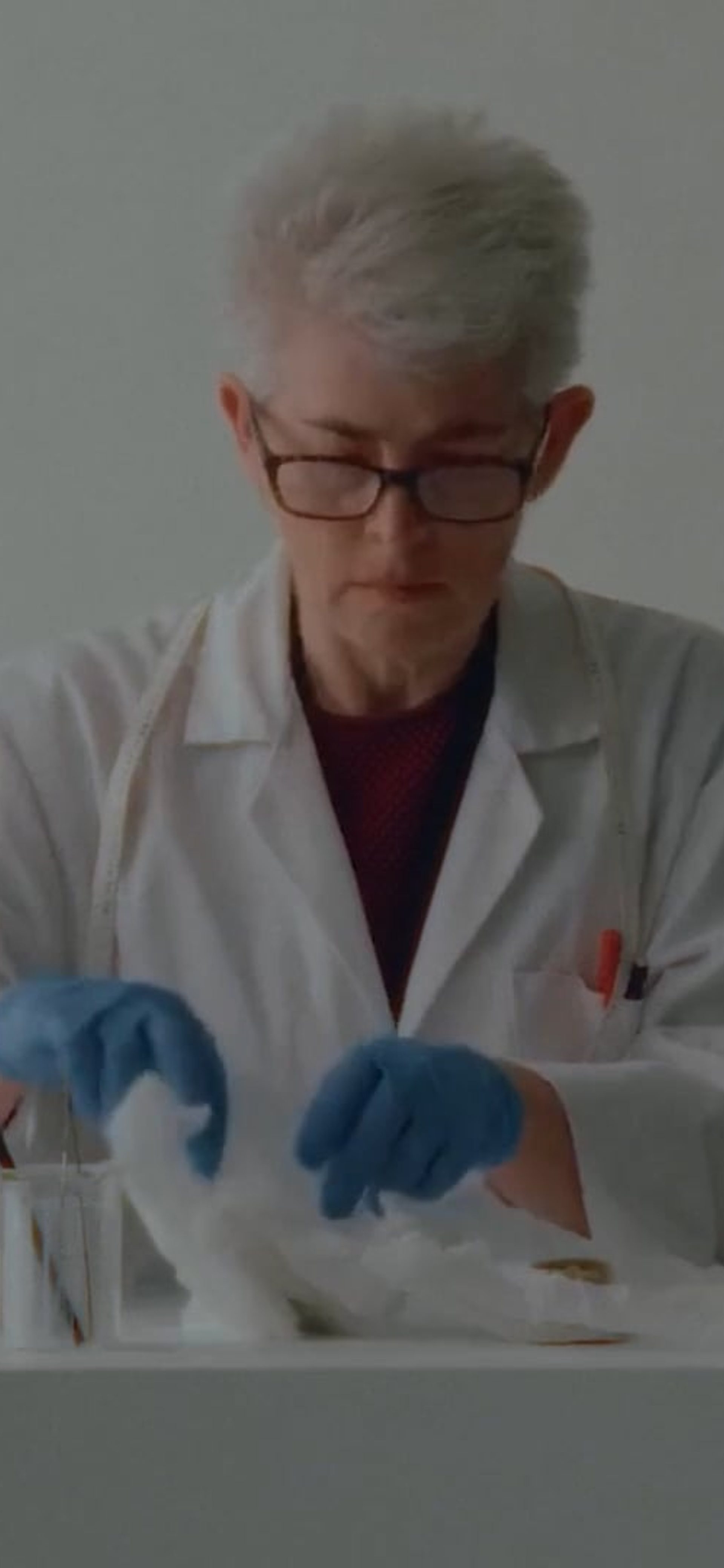

Sophie Netchaef

Head of Research, Library, Archives and Records

‘I’ve always worked in galleries and museums since studying art history and theory in the UK and and I love being part of the organisation at this new stage of its 140-year history. The work we do is very much about reflecting on and reconciling what’s happened in the past and bringing it into the future. It’s not just the strange garden of objects you walk through, which is incredible, it’s also the relational aspects of those objects and the stories you tell when you put one thing next to another — the knowledge and expertise here is incredible.

Collaborative relationships are extremely important. The thing that drives me is modelling new mechanisms for research-led practices and building those relationships with other people and organisations. My area of interest is in the philosophical principles of technology to inform artistic models: what we can do differently to support artists and how this can be part of the great experiment. At the Serpentine in London I collaborated with people in the ArtsTechnologies group to set up the research and development program working with artists in advance tech. I think in the art industry we tend to look inside ourselves, so anything we can borrow from tangential industries like tech is useful. It’s a huge part of our lives now.’