One Man for Many Fishes

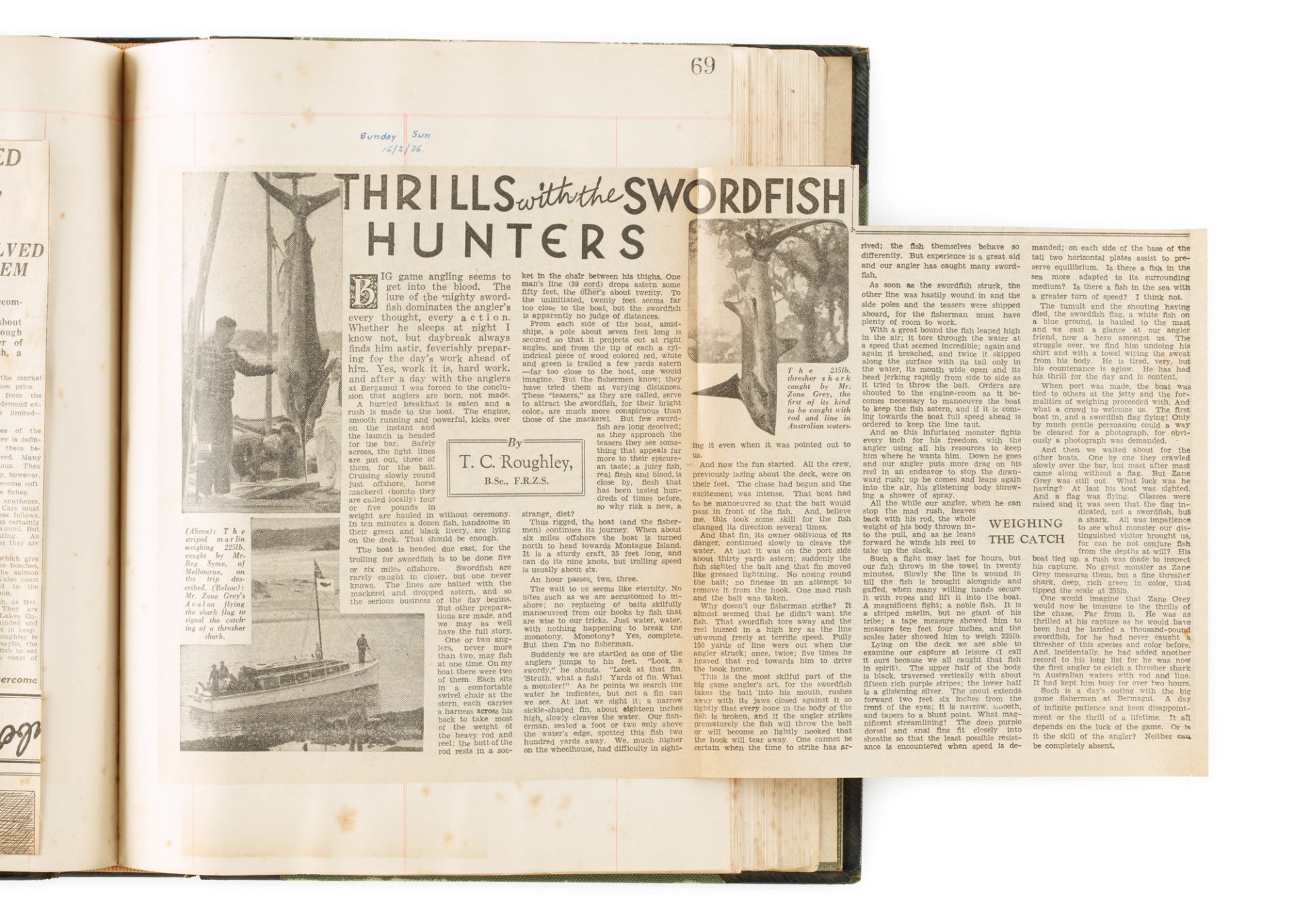

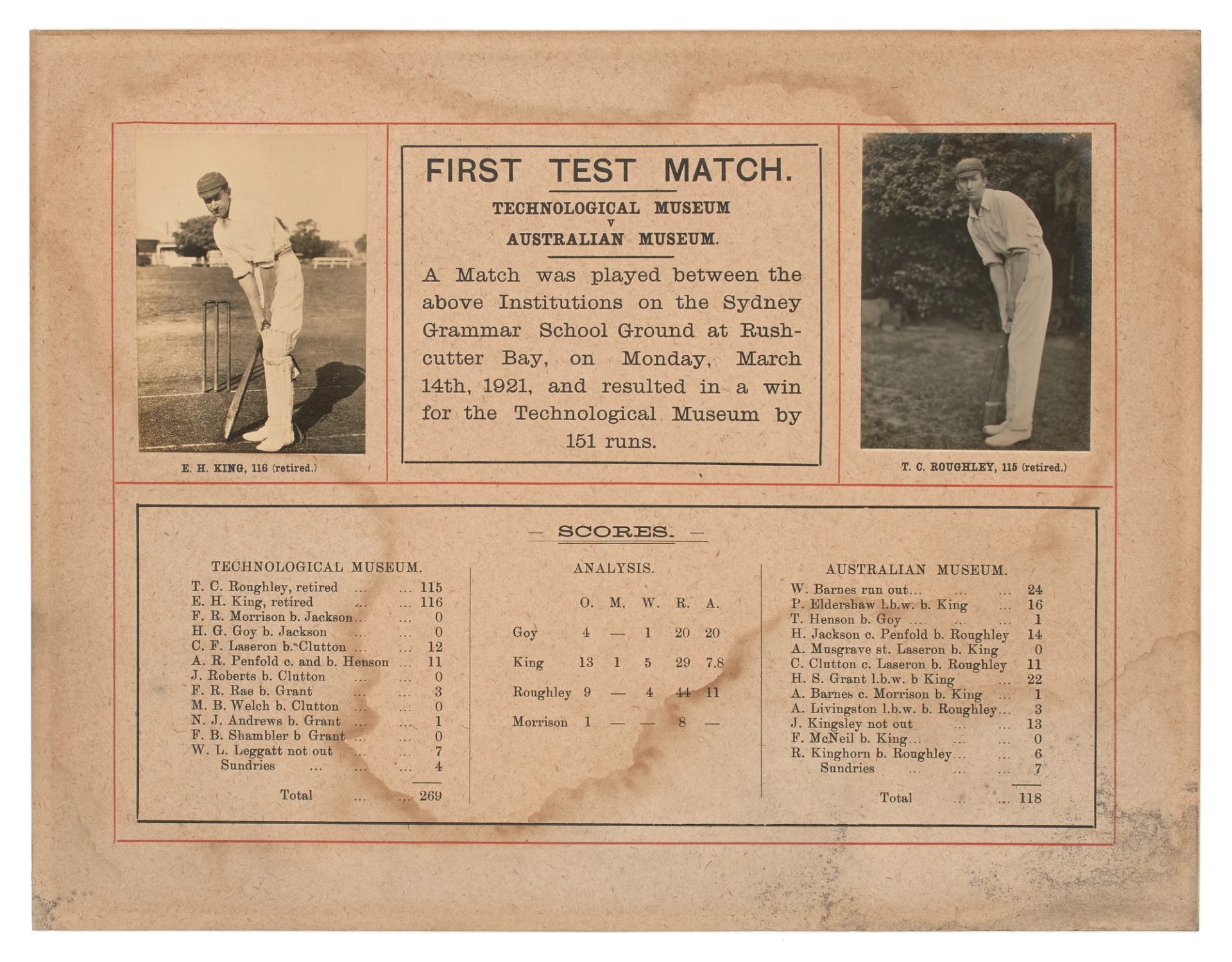

Vicki Hastrich, author of The Last Days of Zane Grey and Night Fishing, has been commissioned by Powerhouse to write about objects in the Powerhouse Collection. In this work she tells how early economic zoologist T C Roughley became a pioneering champion of Australia’s ocean life.

Harris Street, Ultimo, on the western edge of the city of Sydney, about 1915. The smokestacks in the distance belong to the Ultimo Power Station and belch out coaldust that coats the industrial suburb. Factories, quarries, woolstores and flour mills make up the neighbourhood, which is also home to the Technical College, handily placed where future workers can learn their trades. In front of the college is a companion building – the Technological Museum – and it’s from an upper storey of that establishment that this photograph is taken.

A few years earlier a young man walks along this grimy street, perhaps with an umbrella in his hand because the weather is cold and rainy that Monday, 21 August 1911. I’ve been on the trail of this tall slim 23-year-old for a couple of months, finding out the story of his life’s work through objects held in the Powerhouse Collection. His name is Theodore Cleveland Roughley and he’s heading for the museum. He has a brain for science, but he is that loveliest of things – a well-rounded human being. He is an excellent sportsman, a skilled artist, a serious photographer, a book lover and an articulate and entertaining communicator. He’s also a university dropout. Born in Dulwich Hill in 1888 and educated at Sydney Boys High, he is here because, after three years of studying towards a medical degree at the University of Sydney, he has realised the illnesses of people are not his real interest. But as he steps through the door of the museum to take up his first job as the new economic zoologist, he cannot know that he’ll find a subject to intrigue and engage him for the rest of his life. The neglected fishes of Australia are soon to have a champion.

The museum Roughley joins (which will become Powerhouse) is organised into what’s quaintly known as the ‘three kingdoms’ – economic geology, economic botany and economic zoology – with each given a floor of the building for exhibits. The institution is deliberately located in a working-class suburb to encourage working-class people to access it and learn from its displays. But by the time Roughley arrives, exhibits are secondary to the museum’s other role as a provider of research and information to state government, business, schools and the general public on the commercial uses of Australia’s natural resources. Although anything animal is Roughley’s domain, about 12 months after his appointment he sees he will have to choose a subject to specialise in. He decides on fish and fisheries.