CG There was commercial harvest industry for oysters, right around Australia. They would pull their boats up and essentially mow that area. Ultimately, these ecosystems collapsed. We had to look through historical newspaper reports, and then they were able to provide these little snippets of information around how many thousands of bags of oysters they used to harvest before the master decline. We also had parliamentary records and that's phenomenal when you think about it. Within 30 years of European colonisation, they've had to go all the way to the UK establish this act to prevent further harvest because they had already decimated these oyster reefs. And it's so much fun, you know, diving through these historical records, museum reports, photos to uncover this lost ecosystem that we really knew very little about just 10 years ago.

LTL You'll actually find one such record in the Powerhouse collection.

CG One of those gems was Oyster Culture of Georges River and published in the early 1900s. And it described the state of the industry in that transition from being a wild harvest oyster industry through to a managed aquaculture industry. It certainly was a critical piece of information in our historical investigation of what these ecosystems used to look like.

LTL The Aboriginal middens are important records of this loss.

JO One of the things why they're so important is because they provide us information of what was, and what is not there. Now there's a lot of information that these middens provide to us. You can determine the loss of what was there, but you can also then understand how far people had come for those species to be there. So, very important aspect for us to recognise as Aboriginal people, what our people used to eat, what may not be then any more, which is either threatened species are now extinct. So, it's really great to be able to get a picture of the past.

LTL Middens can also provide hope for the future. That's the belief that's inspired Chris Jordan's cooking. Let's hear from the chef as he talks about his evolving relationship with oysters.

CJ I feel like most kids were given an oyster and they thought it was like this slimy thing in their mouth. [laugh]. I do remember stories of my dad eating them off the rocks and really enjoying them. My love for the taste of oysters didn't develop until I was a young adult.

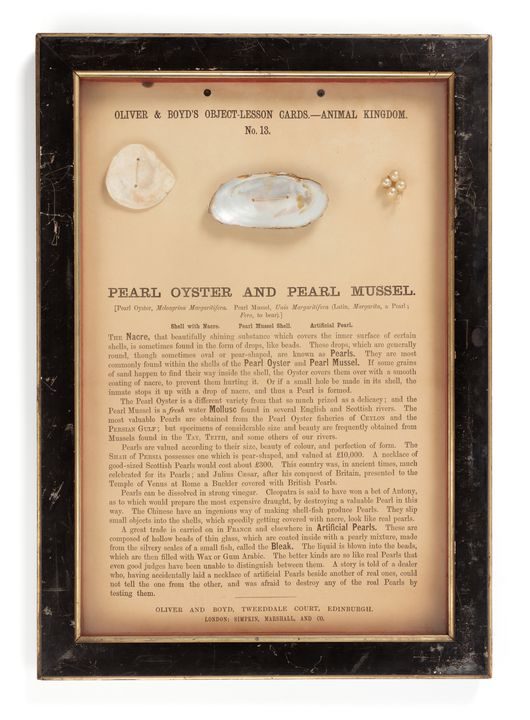

Archival No one has yet defined the correct way of eating an oyster because oyster eating is a highly individual art.

CJ Especially being an apprentice. I was on the raw section in Peter Kuruvita’s restaurant, Flying Fish, and my job was to open oysters. So, we had about six different types of oysters all from, you know, different places. I just remember being blown away by the different, you know, taste and textures and just what like place and temperature and, you know, the tide can do to one thing it's kind of mind blowing actually.

LTL At a certain point, oysters stopped being just another ingredient and became something more significant to Chris Jordan.

CJ I guess it was walking Country with Elders and just hearing about the importance of, you know, shellfish to many coastal mobs, walking a midden with an Elder, with Aunty Bella Douglas down in Currie Country and she was telling me about how the oysters used to be here. Being on Country with Kieron Anderson on Minjerribah and having him explain the population densities and the abundance of seasons that could be seen in the sediment with the oysters. You know, I just felt this real connection. And I guess I wanted to show that in my food. So, my personal experience is something that I really wanted to add to dinners and events when people were eating the oysters. And I think it's really important to share these stories and connect with Traditional Owners, if you're Indigenous or non-Indigenous.

LTL One way Chris Jordan has done this is through a midden-inspired event, which he had originally designed for 2021’s Bleach Festival on the Gold Coast.

CJ That was a three-course dinner part of Bleach Festival down on Burleigh beach. And the first course was the past. So, it was oysters with all these vegetables and fruits that could be found around the middens that I visited, but also like right there on Burleigh beach, it was old oyster shells and rocks with sea vegetables, like sea blight, all foraged on Country with Elders. And then we had these beautiful oysters with like pigface fruit and Warragal greens, oil and seaweed and salt bush. And then we took salt water from Country, and we poured it over dry ice that was hiding in the bottom of the shells and rocks and this kind of mist of seawater bellowed out onto the table.

LTL Chris Jordan thinks traditional knowledge could help avert damage to coast lines and the environment.

CJ The rules and regulations that are in place, the care and the respect hasn't been upheld. I think the steps to rebuild what was once here is through the footsteps of Indigenous knowledge holders and Custodians of the Land.