Soybeans

Culinary Archive Podcast

A series from the Powerhouse with food journalist Lee Tran Lam exploring Australia’s foodways: from First Nations food knowledge to new interpretations of museum collection objects, scientific innovation, migration, and the diversity of Australian food.

Soybeans

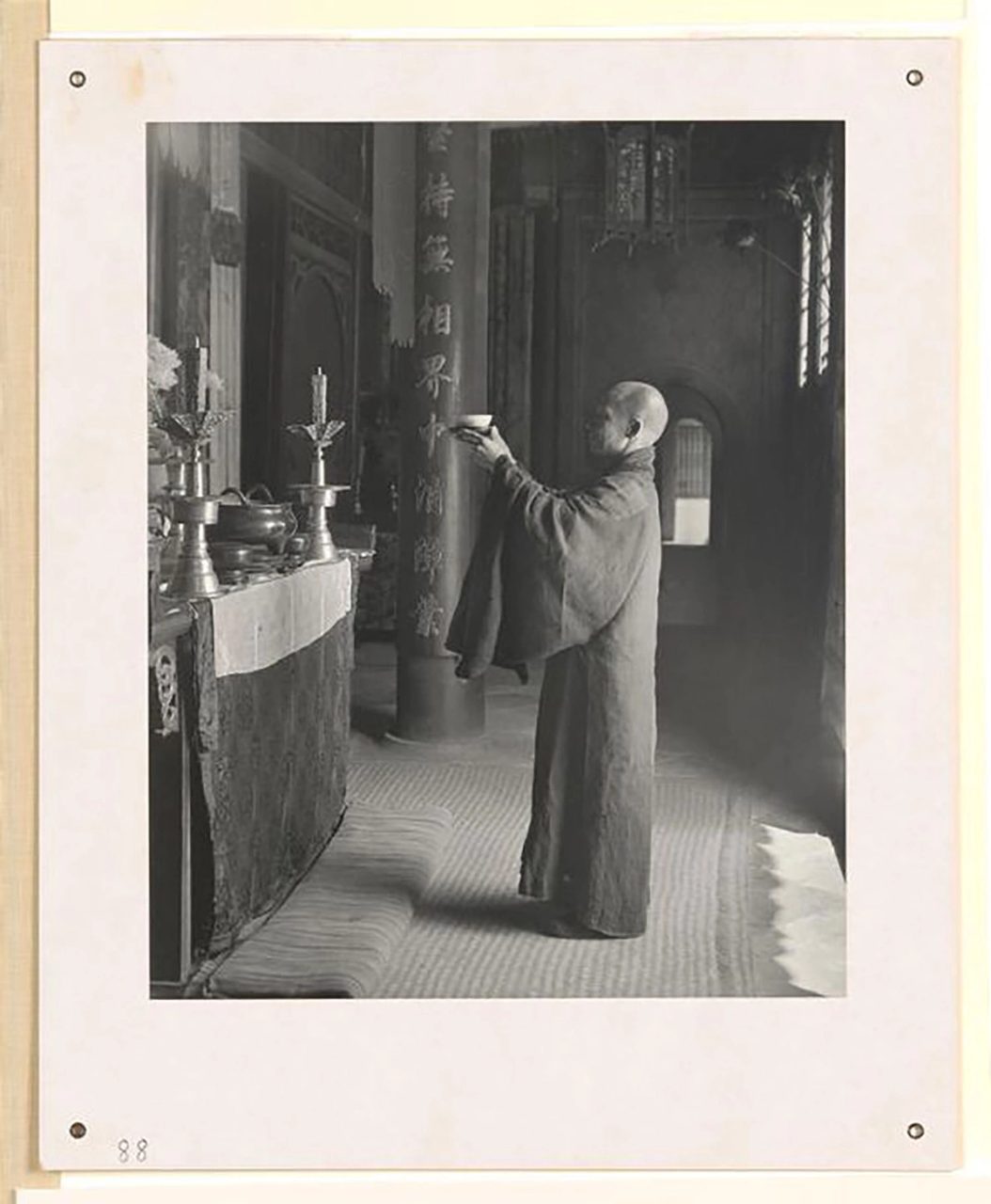

In 1770, naturalists Joseph Banks and Daniel Solander reportedly saw wild soybeans in Botany Bay. The following century, the Japanese government sent soybeans to Australia as a gift. Thanks to Chinese miners in the 1800s, tofu was most probably part of gold rush diets, but it wasn’t until just a few decades ago that the soybean became part of everyday lives. Cult tofu shops, local brewers making soy sauce, artisan tempeh makers and the blockbuster growth of meat substitutes reflect the changing fortunes of the versatile soybean.

‘There are 1 billion uses for soy, and I love them all.’

Transcript

Lee Tran Lam The Powerhouse acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the ancestral homelands upon which our museums are situated. We pay respects to Elders past and present and recognise their continuous connection to Country. This episode was recorded on Gadigal, Bidjigal and Wurundjeri Country.

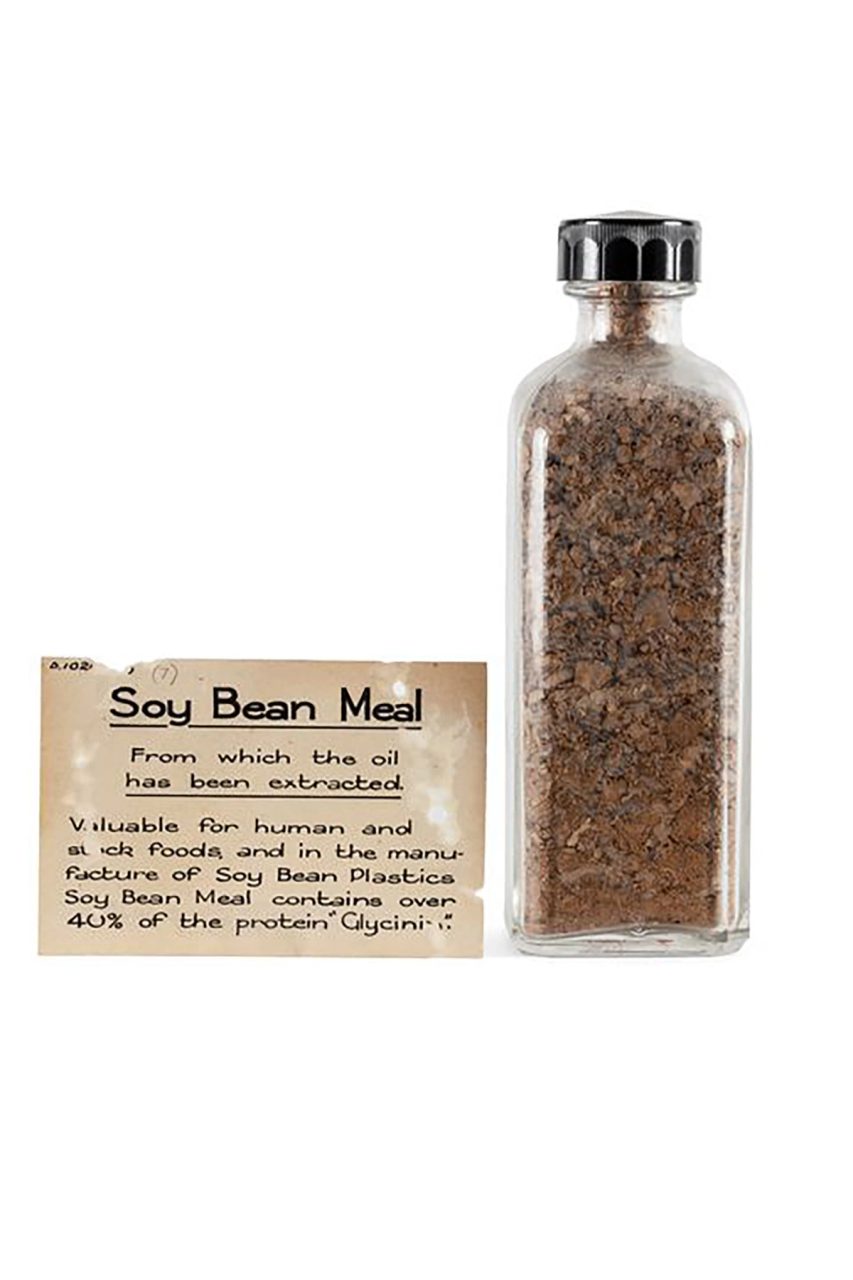

My name is Lee Tran Lam, and you're listening to the Culinary Archive Podcast, a series from the Powerhouse museum. The Powerhouse has over half a million objects in its collection; from yellow soybeans collected in China in 1914; to soybean products that might have been made for car maker Ford, the collection charts our evolving connection to food.

The museum's culinary archive is the first nationwide project to collect the vital histories of people in the food industry, such as chefs, producers, riders, and restaurant owners who've helped shape Australia's taste and appetites. Today we're talking about .