Tomatoes

Culinary Archive Podcast

A series from the Powerhouse with food journalist Lee Tran Lam exploring Australia’s foodways: from First Nations food knowledge to new interpretations of museum collection objects, scientific innovation, migration, and the diversity of Australian food.

Tomatoes

Italy dismissed the tomato as poison for 200 years, though it’s now celebrated as a staple of its cuisine. Then, Italian migration to Australia helped make the tomato a mainstream ingredient here. Learn about the people who grow it, preserve it or cook it – whether it’s Italian Australians bottling passata in their second kitchen, the Cambodian refugee family growing heirloom tomatoes on a former zoo, or the Indigenous café owner serving bush tomatoes on her menu.

‘It always opens the conversation because people don't even know that we have a native tomato.’

Transcript

Lee Tran Lam The Powerhouse acknowledges the Traditional Custodians of the ancestral homelands upon which our museums are situated. We pay respects to Elders past and present and recognise their continuous connection to Country. This episode was recorded on Gadigal, Wurundjeri and Noongar Country.

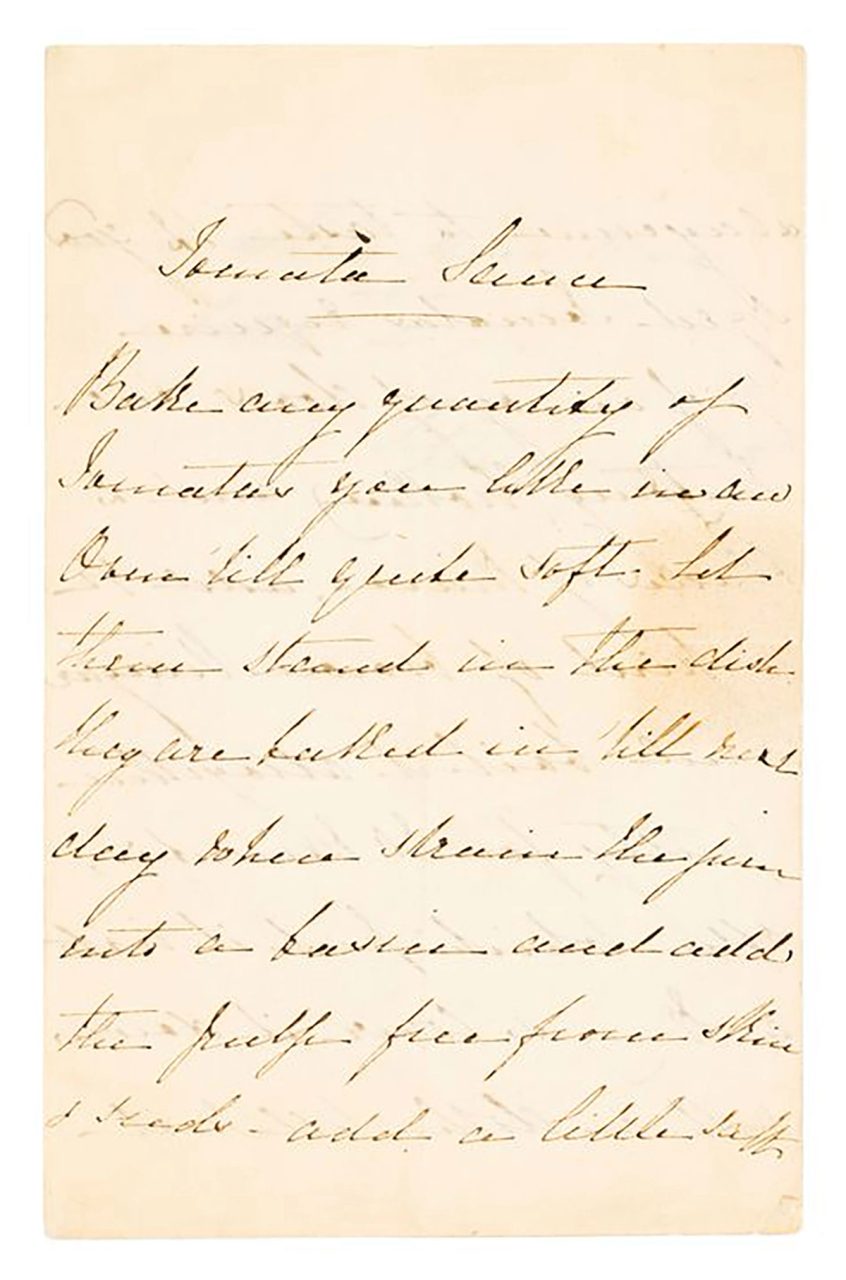

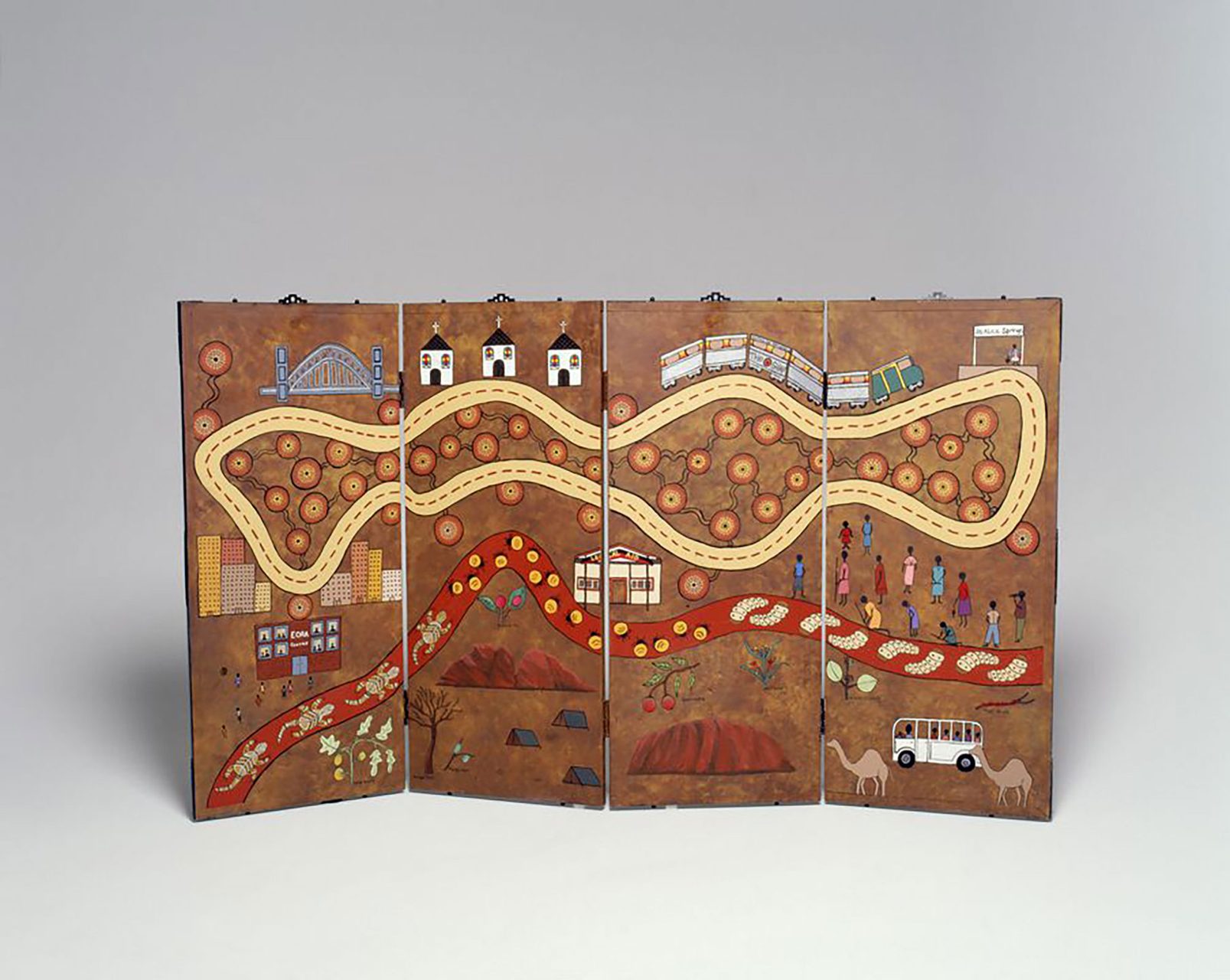

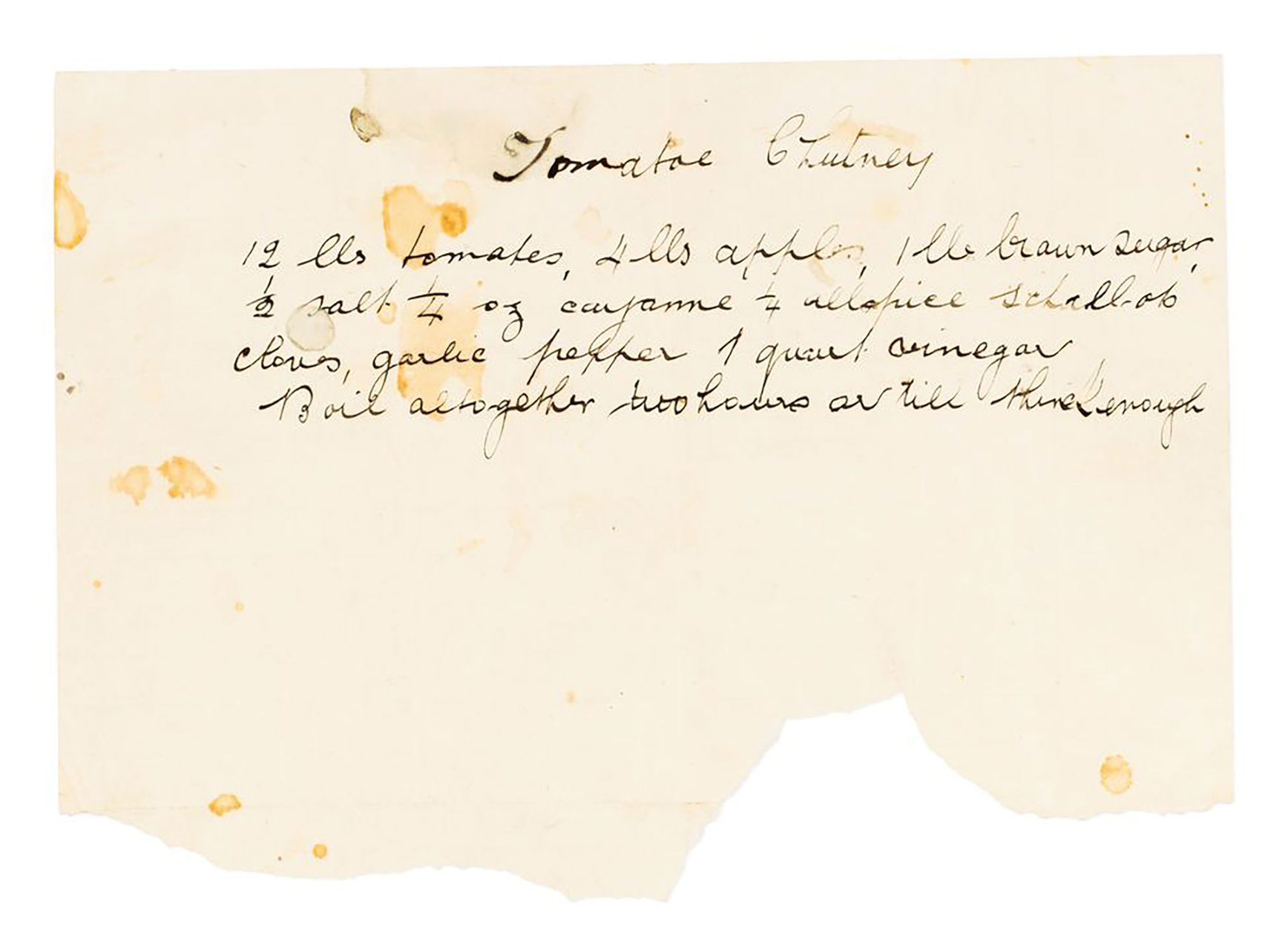

My name is Lee Tran Lam, and you're listening to the Culinary Archive Podcast, a series from the Powerhouse. The Powerhouse has over half a million objects in its collection. From a century old handwritten tomato chutney recipe to an Indigenous bush tomato textile design by Lena Pwerle, to a 23-year-old jar of Nepal sauce made for Ken Done's Sydney Harbour Bridge pasta, the collection charts our evolving connection to food.

The museum's culinary archive is the first nationwide project to collect the vital histories of people in the food industry, such as chefs, producers, writers, and restaurant owners who've helped shape Australia's taste and appetites. Today we're talking about .